Luxury Beach Getaway with a Worthwhile Cause

I want to support Telunas Beach Resort

I want to support Telunas Beach Resort

Visit Cafe Inklusi to get great local food and support the deaf community.

The Magic of Kupang

To most travellers Kupang is a transit hub en route to hiking Mount Mutis in South Central Timor’s Mollo highlands, surfing Nemberala Beach in West Rote, or diving Alor’s coral reefs.

But Indonesia’s southernmost city has its own wonderful charms. From natural splendours like sprawling tropical landscapes, swimming caves and waterfalls, to a scenic city steeped in centuries of history as a trading port, with a waterfront that sets the stage for an amazing sunset.

The Kupang Lighthouse, an historical landmark from the colonial past. The Dutch name for it is Ruïnes van de Oude Indië Pier in Koepang.

To me though, Kupang is my other home. My maternal grandparents were from neighbouring Rote island, so Kupang was their gateway to the world.

I grew up with “Bahasa Kupang” (Timorese Malay), Rotinese songs whose lyrics I’ve yet to memorise, my great-grandmother’s handmade textiles and faded stories of the Timor and Rote my grandparents remembered: pristine beaches, sugar palms, horses and church. As a foodie, one of my regrets growing up was never having the opportunity to savour my great-grandparents’ West Timorese cuisine.

This is what brought me to Kupang's shores - to discover a missing part of my heritage.

It’s a good time to be a foodie in Kupang. A gastronomic revival has drawn many to the city’s distinct culinary heritage. West Timorese cuisine centres around aged maize, fragrant endemic herbs and the local specialty - se’i, Timorese smoked meat, a dish that’s rising in popularity in Indonesia. These flavours are being appreciated in smokehouses, restaurants and hawker centres—by Kupang’s population of 450,000 as well as tourists.

The se’i method smokes meat on beams of Ceylon oak and river tamarind wood, covered with their leaves. The result is a deep pink meat with a bold and spicy smoky flavour.

There is one special place in Kupang that does more than just delight my tastebuds. It tugs at my heart strings as well.

Artisan coffee bar Cafe Inklusi (CafeIn) serves Timorese fusion dishes and native coffee from all over the Nusa Tenggara Timur (NTT) province. They also serve a great cause. Employing predominantly deaf cooks and baristas, CafeIn’s mission is to transform Kupang’s food and beverage (F&B) landscape into an inclusive intercultural space to bond over food and coffee.

My mission: to meet these people, learn from them, make new friends and reconnect with my heritage.

The CafeIn crew sign hello.

Meet Cafe Inklusi

“Warming people’s bellies with food is the simplest form of happiness.” Sischa Solokana is proud of her establishment which she co-founded in 2019 with her cousin Kichi Jacob.

Back then, it was called Kopi Saa. Today it has expanded to become Cafe Inklusi, with the cafe operating in Dekranasda, the province’s colourful handicraft centre. With Sischa now a member of the Indonesian Chef Association, and Kichi a certified barista, Kopi Saa lives on as their F&B training programme.

There haven’t been many options before for Kupang’s deaf community to find jobs, so CafeIn, along with its weekly training, provides them with an opportunity to be empowered, engaged and to have something to care about.

Kopi Saa/Cafe Inklusi co-founders: Kichi Jacob (left) in the CafeIn barista apron and Sischa Solokana in the Indonesian Chef Association uniform.

The heart of the operation are the 2023 CafeIn crew - An Mone, Daniel Yohanis, Frengki Riwu, Misel Elik and Tanel Loa, who are deaf, as well as the hearing Doni Kopong and Nona Saekoko.

CafeIn’s working language is BISINDO, an Indonesian sign language. Currently only Sischa and Kichi speak English. Diners who do not know Indonesian can communicate using apps like Google Translate.

As an amateur cook, I suggested an intercultural cookout, experimenting the Timorisation of my and Sischa’s favourite Western recipes with the deaf community.

Sischa and Kichi respond delightfully. “Let’s do this!”

A Timorese culinary excursion

What is “Timorising” fusion cuisine? For Sischa it is all about adapting locally.

“We aim to serve dishes that are familiar to most travellers, but with a novel twist. We use local ingredients whenever possible. Timorese parsley instead of rosemary. Virgin coconut oil instead of olive oil.”

“Timorising” requires an understanding of authentic Timorese flavours, so CafeIn invites me to a food excursion at artisan smokehouse Se’i Baun in Kupang’s outskirts. An important part of training at CafeIn, Sischa says, excursions help staff learn from other businesses.

Se’i is the centrepiece of Timorese cuisine. Commonly pork, se’i could also be beef, fish or chicken produced with the same smoking technique: on Ceylon oak or river tamarind wood and leaves.

Its smoky taste is bold and bacon-y like hickory but muskier and spicier. It tints meat deep pink like cherrywood. Se’i Baun’s cinderblock furnaces spread a delicious barbecue scent of smoking premium free-range pork.

Pork se’i has a fuller-bodied smokiness and thicker cuts. Se’i Baun is served with a blazing traditional chilli-citrus relish sambal lu’at, as well as smoked ribs, and a stir-fry of bitter greens.

An excellent se’i meal is both earthy and zesty. Fiery and buttery. Succulent and hearty.

A cook at the Se’i Baun smokehouse puts fresh pork on the smoking furnace while directing the junior staff.

Kichi, who created se’i based cocktail Royal 1917, says se’i was invented in colonial times. Plantation labourers left home months at a time and needed to feed their children while away. Hence the invention of se’i, fermented sambal lu’at and aged maize jagung bose—all which keep for months without refrigeration.

Founder, Kichi Jacob’s Royal 1917 is a beef se’i infused whiskey cocktail with a creamy texture and refreshing citrus and basil flavour. Accompanying it is a micro serving of beef se’i and sambal lu’at.

A Timorese fusion experiment

While se’i cannot be cooked in CafeIn’s kitchen, it is Sischa’s favourite ingredient for fusion creations. CafeIn is applying for Halal certification and only serves locally sourced halal se’i.

At CafeIn, Sischa demonstrates cooking beef se’i Alfredo and tuna se’i aglio e olio spaghetti for the CafeIn staff, who take turns helping her. Neither dish contains added salt or olive oil, with Se’i and virgin coconut oil being used instead. Coconut cream substitute for cooking cream in the Alfredo. Aromatic leaf celery substitute for European parsley.

Now it’s my turn to lead, and as I knead the dough, I pique An’s interest. She loves to bake but is new to bread, so I invite her to shape submarine rolls together. Her eyes light up as the dough expands.

Born and raised in Kupang, 19-year-old An recently graduated from high school. CafeIn is An’s first workplace, but she has been cooking since primary school.

“My mother taught me to be independent, including being able to feed myself. I felt happy and proud when my mother came home from work and I have dinner ready for her.”

An adds that she loves fish dishes, jagung bose porridge and sambal lu’at—the hotter, the better.

Grace and An make submarine rolls. An loves to bake but this is her first time making bread from scratch.

Up next, Daniel, Tanel and Frengki prepare roast chicken.

Originally from Soe, South Central Timor, 19-year-old Daniel has had a traumatic childhood. He and his mother endured violence from his father, who did not accept having a deaf child. After Daniel’s parents separated, the 11-year-old boy walked alone from Soe to Kupang, about 110 kilometres, to find his mother.

Daniel has since graduated from high school and developed a passion for brewing coffee. Overcoming trauma is an ongoing challenge, but having joined CafeIn in April, he now has a chance to feel appreciated and let his talents shine, in the presence of positive role models like Sischa and Kichi.

Locals may recognise 27-year-old Tanel as a BISINDO interpreter for a national television network. But Tanel wasn’t always busy with two jobs. “I used to have difficulties finding a job, but CafeIn gave me and my deaf friends a chance to make something of our lives and contribute towards a more inclusive NTT Province.”

Previously aspiring to become a photographer, today Tanel looks at the barista profession as his future. Tanel finds his barista apprenticeship at CafeIn a much more fruitful pursuit than photography. He recollects the frustrations he felt in photography spaces that assumed all photographers were hearing.

Tanel is currently saving to open his own cafe. “Baristas are cool. I am proud to be a deaf barista."

(Left to right) Baristas Daniel, Frengki and Tanel step out of their comfort zones and rise to the cooking challenge.

Back in the CafeIn kitchen, we work on Timorising my favourite roast chicken recipe. We use limes instead of lemons, and Timorese herbs instead of rosemary and thyme.

The red stemmed Timorese basil is fresh, spicy and sweet with hints of licorice. Sipa is a peppery, minty mini-parsley with an intense palate-cleansing punch. The citrusy and nutty cilantro is also a Timorese staple, and a first for my roast chicken.

Frengki panics as I demonstrate peeling garlic. “Slow down,” he signs. Sischa later informs me that Frengki lost his hearing in an accident, so he fears sharp objects.

After becoming deaf, Frengki used to lock himself at home, but over time and with support he found more confidence and employment.

“Even when I got hired by CafeIn, my parents were initially sceptical, because deaf workers often get paid less than they’re worth. But now that I’m paid what I’m worth, I have my parents’ blessing.”

Stuffed and salted! A chicken is ready to roast.

Hours later, we completed the dinner spread with guacamole-roast chicken sandwiches, a refreshing cucumber-grape salad with Timorese honey vinaigrette, and jagung bose porridge cooked in bone broth from today’s roast chicken, coconut milk and beef se’i bits.

I am pleased with our creations, and so are my new friends.

“Making roast chicken was fun! I didn’t know garlic, citrus and green flowers make chicken taste good,” says Daniel, who had only “cooked” instant noodles before.

As a first-timer in a deaf space, I feel truly included in my new friends’ generous spirit. Cooking together meant we were all out of our comfort zones: mine linguistically and theirs culinarily. Yet in this feast of few words, food becomes a common ground for us to bond past our cultural differences.

Making new friends and bonding over food.

Future Focus

CafeIn staff are meant to “graduate” within a year or two and continue their careers elsewhere. Frengki, Tanel and Daniel plan to open their own cafés. Misel, also a makeup artist, is saving to open her own salon. Nona and Doni plan to attend university.

An is still figuring out her future, but as her paralysed mother’s caretaker she plans to provide a good retirement for her parents.

“I am grateful. With skills gained from CafeIn, I feel secure about my future,” says An.

While the staff continue to grow in skills and confidence, CafeIn is evolving as well. In their bid to continue advocating for inclusivity in the F&B sector, they have formed a training partnership with a local special needs school.

In the near future, they also intend to hire employees with other disabilities, or hearing/able-bodied employees with disadvantages such as school leavers, young people fleeing from abusive homes, and those from low-income families.

And in mid 2023 Cafe Inklusi will open a second location in Tedis Beach, a trendy district near the waterfront at the Old City district.

“Please come! We serve good dishes and beverages. Come get to know us,” says An.

CafeIn is closed on Sundays, except for secret menu bookings made in advance. This gives you access to dishes not on the daily menu, and helps CafeIn tailor the ingredients to your dietary requirements.

A Full Belly and Full Heart

CafeIn has been a rare opportunity for me to engage in a deaf space. Not always easy for me, who is used to long conversations. What I learnt was that at CafeIn food is just as powerful a tool for building friendships.

Unlike almost everything else in life, food is a space where it doesn't matter who is hearing or deaf. Even in near silence, in this space we are just fellow cooks, eaters and human beings enjoying the pleasures of life together.

Ready to feast: a whole day of cooking followed by 10 minutes of eating.

CafeIn’s menu might not look like my great-grandparents’ traditional cooking, but their Timor-inspired fusion creations speak so primally to my diasporic soul. A piece of my heritage—our common heritage—is present in the dishes in a way that I am proud to call my own.

Our “Timorising” experiment has been more than just flavours to me: it is an expression of my identity as a world citizen with roots in Kupang, made special by a group of new friends in this special city who show me what the Inklusi (inclusive) spirit truly means.

I hope in due time, the hearing world will learn to reciprocate.

While Kupang may well be known for its old world charms, colonial history and its position as a great transit for the dive, sand and sea holiday, today it is gaining recognition as a culinary destination.

Helping put Kupang on the food map is Cafe Inklusi - in a very special way. When you visit Cafe Inklusi your act of eating there and supporting the staff will go a long way in helping deaf baristas and cooks. The hearing founders of Kopi Saa/Cafe Inklusi Kichi Jacob and Sischa Solokana hire only the members of the deaf community in Kupang. The training they get will go a long way in helping them secure a bright future.

Book a rainforest experience with Green Hill

Trekking through a jungle in the mountains. Chugging up and down precariously steep dirt roads on scooters. All while balancing heavy loads of rice, fresh produce, spices and other food items — necessities to nourish families in Bali on the verge of having to do without.

It’s all in a day’s work for Wayan Ariani and Made “Arry” Pryatnata who have been traipsing all over Bali to deliver food packages to its most remote communities, who are hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this traveller’s paradise, the past year has been “a nightmare” for the many who depend on tourism for their livelihoods, as Wayan puts it.

One moment, Wayan and Arry were villa managers at different properties, catering to the thousands of travellers that throng Bali each year to revel amid its beautiful beaches, views of lush paddy fields, and rich culture.

The next, they were out of work, as COVID-19 led to a sudden halt in international travel, and tourism dollars dried up overnight.

“We stopped work, but we have to continue paying our debt, for our [temple] ceremony, daily expenses and also for my children's school,” Wayan shares.

Arry adds: “Now, everyone wants to sell everything, sell the car to get something, buy some food for the family. That's very, very sad.”

Fast forward a year, and neither have gotten their jobs back, but they are fuelled by their new mission of delivering food to Bali’s neediest — through Feed Bali.

Feed Bali is the brainchild of Adi and Frances Tse Ardika, founders of Tresna Bali Cooking School.

As the pandemic took hold in Bali in March 2020, the couple, who have been married 18 years, decided to close their cooking school and cottages. Seeing their fellow villagers caught short by the shutdown and without income, they started a “Feed a Family” initiative to give food packages to families so that they could shelter at home as the pandemic spread, and eat nutritiously.

Their goal was modest — to help 20 households around their school with food packages that would last two weeks for a family of four. Adi and Frances asked their friends and network of former guests to contribute funds for the packages, to mark their daughter Santi’s birthday.

The response from donors was overwhelming. “For the first two months, it was just Adi, Santi and me, to avoid any contact with others. Our day started at 4am going to the local market to buy vegetables, fruits and eggs.

“Adi harvested spices from our cooking school gardens to donate immune-building ingredients and encourage our neighbours to plant their own spices. Santi and I packed the massive food packages. Together, we’d pile one package into a wheelbarrow to bring to each home in the afternoon,” recalls Frances.

“By the end of April, we were exhausted. We wanted to use up the rest of the donations and stop.”

But when they shared the news on their social media platforms, their community urged them to keep going. “They were like, ‘You have to keep going, who else is going to do this?’” says Frances.

With donations and suggestions coming in, Frances and Adi, former wedding and travel planners, decided to muster their organisational skills and launch a full-fledged operation — hiring a core team (among them Wayan and Arry) to help plan and execute Feed Bali’s distribution.

Integral to this were their Balinese roots and connections: Adi, who is Balinese, and Frances, who is Canadian, serve as holy people for their village, leading the Hindu temple ceremonies that are an important part of Bali's spiritual life.

“We have lots of requests for help, my phone is almost exploding with messages,” says Adi, who painstakingly looks into each request by visiting the household to assess their needs, and consults village leaders on the ground situation.

“I have to classify them like, the ones who need it most. It's always difficult to choose who to give to, but we have to make the hard choices,” he says. “To be honest, most Balinese need help now.”

Arry and Wayan receive two food packages from Feed Bali each month, as well as a “survival salary” of IDR150,000 (US$10.50) for every day they volunteer (about four days a week). This is a fraction of what they used to earn as villa managers but is more than many are earning on the island now, shares Frances.

“The food package is very important. Because we have food, I can save the [survival salary] for other needs, go to the doctor, things like that,” says Arry.

With no end to the pandemic in sight, Adi and Frances set a goal of distributing packages to 2,300 households by the end of 2020.

As of May 2021, they have reached 3,540 households, equivalent to 396,480 nutritious meals.

“So as long as we have donations, we will keep going,” says Adi.

On most mornings, Wayan is up by 4am, ready to start another day at Feed Bali.

Every Feed Bali package comprises 10kg of rice purchased directly from Balinese farmers, cooking oil, 30 locally-farmed eggs, salt, and kilos of fresh vegetables, fruit and aromatics like ginger, among other items. Fresh local produce is an imperative, with the team determined to provide nutritious food to the villages while supporting local farmers by buying their harvest.

“It has to be 4am because we want the very fresh chillies,” says Wayan, a note of pride in her voice. “There are mini trucks that sell them wholesale at the morning market.”

She then returns home to cook breakfast for her family, before heading back to the cooking school to pack the spices for distribution. After packing hundreds of bags of spices, Wayan and her husband, Made Gunarta (Gun) drive an hour north to the Kintamani area to buy fresh vegetables directly from farmers. “We finish around maybe 5pm,” says Wayan.

On distribution days, the team starts their journey as early as 6am. “To East Bali or North Bali, we have to be at Feed Bali at least 6am, and then by the time we come home, it is around 7pm,” says Arry.

Adds Adi: “We go from house to house, and it’s not like, you go to this house and you see the next house right after that. You go to the jungle, trek through the jungle, and then you see the next house.”

The villages receiving support also stepped up, with some volunteering to coordinate deliveries on the ground, especially when the homes are deep in the mountain or jungle.

These journeys have been eye-opening for the Feed Bali team. “I meet more people, I see many villages, and to see the poverty, to see so many people in need,” says Wayan.

Frances adds: “Most people only see Bali as a luxurious, paradise island in the media. People working in hospitality, maybe they have a house, or a car, but they have no savings.”

Communities living in poverty could previously rely on hospitality workers’ donations; when these workers lost their jobs, this precarious safety net vanished. “It makes me very sad that I cannot help them with money,” says Wayan.

Although very much connected to their village, Adi and Frances did not set up Tresna Bali Cooking School with a social mission in mind. “We started with the intention of sharing our authentic Balinese food and culture,” says Frances. “Adi and I are highly involved in our community, our banjar (Indonesian for neighbourhood), but it was a personal thing, it wasn’t anything tied to our banjar or Tresna Bali.”

The pandemic has opened their eyes to how their business could also be a platform for guests to give back to the community. “We have discussed how we can tie Feed Bali to our cooking school, maybe if you book a cooking class, you can also opt to feed a family,” says Frances.

They have also started a programme dubbed Baa Baa Goat, where they have built a goat shelter and donate goats to impoverished families living in remote, arid areas where growing crops is not an option.

Through Feed Bali, a goat farming expert advises the family on how to breed healthy goats, and the goats’ milk can be sold for additional income. The offspring of the goats will then be donated to the next family, creating a long-term, sustainable plan to improve livelihoods.

“Sometimes people just need a hand. When we extend that hand and give support, everything changes,” says Frances.

An early “pioneer” of this programme is Wayan and Gunarta and their teenage children, who plan to sell the goat’s milk for extra income, while future generations of goat will be given to another qualified family.

The additional income is welcome, as there is no clear idea when things will “return to normal”. “When tourists come back, maybe it will be very slow. Even if some tourists come, we have so many hotels and villas, it will be a struggle to get guests,” says Wayan.

Amid the challenges, there have been many moments of hope. “When we first started giving out food packages in our village, we identified a few families. And we had gone to three families, and when we reached the fourth family, we found that the third family had already given the fourth, half their package,” says Frances. “We were just blown away. They still thought of their neighbours, even when they were struggling.”

Working with Feed Bali, says Arry, has taught him the value of sharing what he has, no matter how seemingly small. “I don’t have a lot, but a little thing can make others happy,” he says.

Bali’s economy is highly reliant on tourism, which accounts for some 60 to 80 per cent of the island’s gross regional product. The slowdown in tourism has affected some 80,000 people, who were either laid off, put on unpaid leave, or had their wages cut. This estimate does not include the vast informal sector of freelance drivers and independent guides.

Donations to Feed Bali go towards the food packages that are delivered to households in need all over Bali. Feed Bali sources food directly from local farmers (instead of imported foods found in supermarkets), so that farmers too benefit amid challenging times.

The donations also pay for the expenses of transporting the packages and survival salaries for Feed Bali’s core team of six.

A donation of US$30 buys food for a household of four for two weeks, but any amount is welcome. Feed Bali also welcomes donors who wish to “adopt a family” by donating towards more substantial needs, such as home repairs; 10 families have been adopted so far.

To date, Feed Bali has received some Rp2 billion (US$140,000) in donations and counting, of which about Rp1.5 billion (US$105,000) has been used for care packages and projects like Baa Baa Goat. Frances and Adi estimate that the remaining funds can help another 1,000 families.

I want to Feed Bali

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways you can support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, is there a more iconic accessory than the ubiquitous face mask?

On the website of Noesa, a Jakarta-based favourite among the sustainable style-conscious set, face masks made with beautiful ikat fabric are front and centre, as part of their Corona Survival Kit collection.

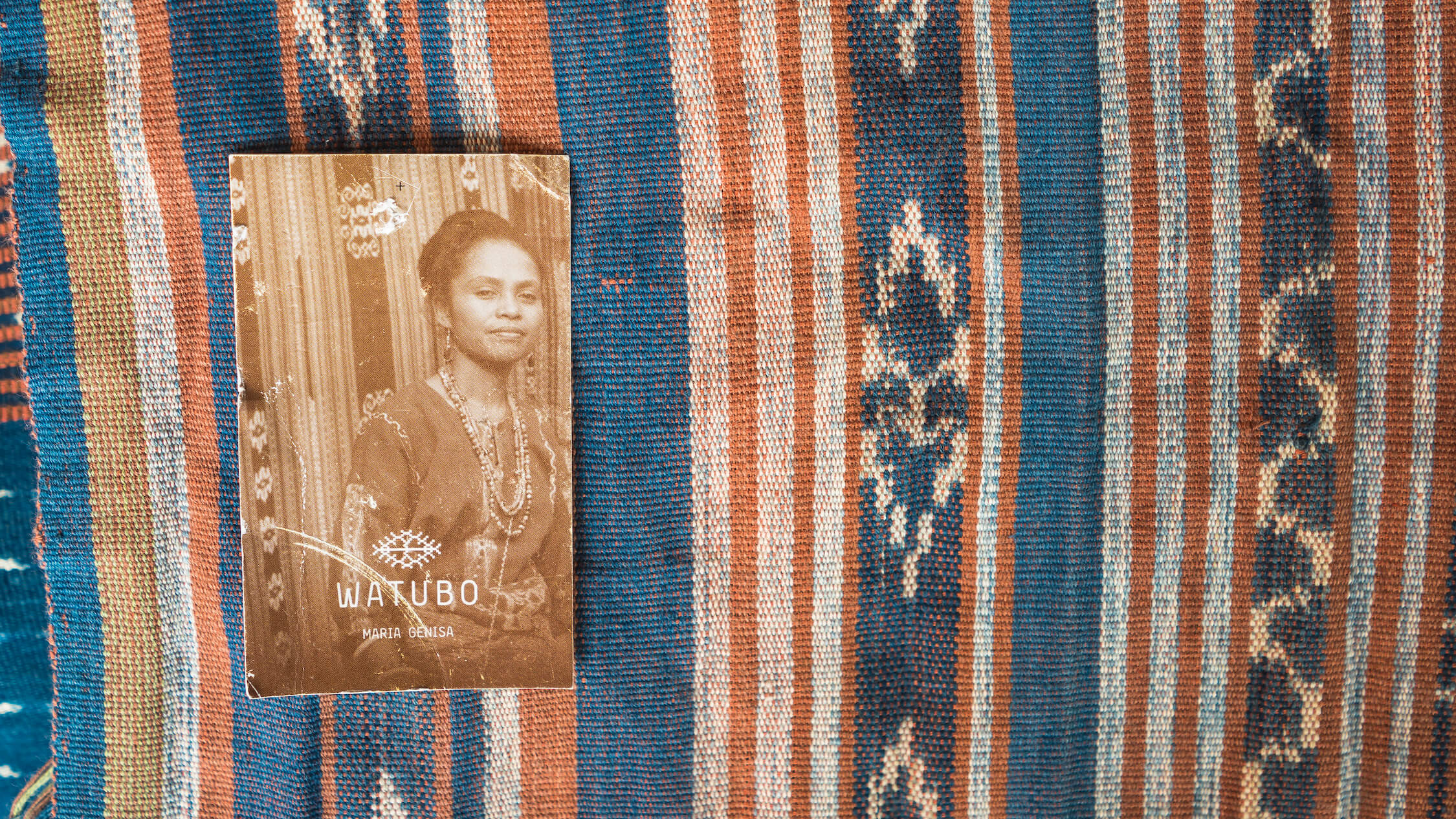

But these colourful textiles are more than just a symbol of these unusual times: they are part of the tapestry of empowerment and cultural preservation woven by Watubo, a collective from Sikka regency in Flores, Indonesia.

A traveller could once participate in a weaving workshop by Watubo in their village of Watublapi, which provided the weavers a vital source of income while safeguarding their craft. But the pandemic has ground these efforts to a halt.

With a little help from customers looking for something special, Watubo weavers hope to restore not only some of their income, but also their platform for sustaining and reinventing their ancestral craft.

“Ikat represents a woman’s worth,” says Rosvita Sensiana, an ikat artist with more than 20 years of experience. “Our ancestors didn’t have clothing stores, [so] to clothe her children and husband, a Sikkanese woman toils with her body to weave ikat.”

Ikat means “to bind” or “knot” in Indonesian languages, and Sikka regency is one of the most reputable producers of fine ikat in Indonesia, with centuries’ worth of vegetable dye traditions. Born into a family of Sikkanese master weavers, 36 year-old Rosvita is the founder of Watubo.

Before the pandemic, Watubo made most of its income from taking part in national and international exhibitions, as well as hosting travellers to its ikat workshop, where participants could learn the craft while enjoying the sights, sounds and stories of Sikka.

All this changed when the pandemic struck in 2020, but Rosvita is confident that Watubo will find a way to prosper again. “Watubo means ‘breathing rock’ or ‘living rock.’ It represents our belief that no matter how hard a place is, we will certainly survive,” she says.

I met Rosvita in 2019 before the pandemic when I took part in Watubo’s ikat workshop, a collaboration between Watubo and Noesa.

“An ikat workshop would attract visitors, which would help promote Watubo and increase weavers’ earnings,” said Rosvita then, adding that participants’ respect for ikat is also the goal.

Noesa provided the funds to build a homestay for guests and handled the online bookings. The workshops also included a tour of Sikka led by Rosvita.

But these workshops are on hiatus indefinitely, and for now, avid travellers can only experience the rich history of Watubo’s ikat through the wares sold on Noesa.

Ikat is popular worldwide, but my interest in it is personal. My maternal great-grandmother, originally from Roti island near Timor, was a weaver who clothed her family in elegant, handwoven ikat bearing intricate motifs identifying their surnames.

I never met her, but I still hold a sarong that she wove for my grandmother in the 1950s — an heirloom no one in my diasporic extended family can replicate.Since my family had lost this cultural knowledge, I had come to Sikka to learn from another weaving culture. But even in Sikka, where ikat is considered to be thriving and current, perpetuating the culture has neither been easy nor straightforward.

Many Watubo weavers are alumni of Bliran Sina, an older collective founded by Rosvita’s father, which focuses on the most traditional forms of Sikkanese ikat, and subjects weavers to a myriad of protocols and taboos.

Although Rosvita supports preserving tradition, she believes that innovation upgrades weaver’s livelihoods because it opens up markets otherwise impenetrable by traditional ikat.

In 2014, she started Watubo with Noesa’s support. The collective allows younger weavers to explore creative innovations such as novel colours and contemporary motifs. These updated iterations of ikat can be applied to products such as camera straps and wallets. In contrast, traditional ikat bear sacred images and cannot be used in the same way.

Watubo became Noesa’s first artisan partner, connecting its weavers to Noesa’s urban consumers, and becoming a success story of a woman-led rural creative enterprise.

A former Roman Catholic kingdom that ruled parts of central Flores from 1607 to 1954, Sikka may not have royal heritage sites matching Java and Sumatra’s grand royal palaces , but it can hold up ikat as one of royal Sikka’s biggest remaining testaments.

It is a discipline that is not only arduous, but also easily rendered meaningless when divorced from a practicing community and their culture, which provide ecological and historic context to the craft.

Watubo’s workshop, named Orinila (“House of Indigo” in Sikkanese), aimed to preserve this connection. Guests are welcomed with a ceremony involving dance, music, offerings to Watublapi ancestors, a formal introduction to express the guest’s intention for visiting, chewing betelnut, and a Holy Communion-like ritual of eating chicken and rice.

Next, the weavers and I discussed our lesson plan. I produced a grid paper drawing of my grandfather’s Johannes clan motif, to be woven into a scarf.

No newbie finishes a scarf in three days, so the workshop involves a dozen weavers demonstrating works-in-progress at different stages, and allocating time for a guest to practice each stage. Watubo then completes the scarf and ships it to the guest later.

On day one, I recognised my instructor Maria Genisa, having previously bought her work. Though I had only seen her photograph and name on a Watubo label, it felt like I was meeting an old friend.

Genisa and I spun hanks of cotton thread into balls, and wrapped them around a warp frame. I learned that Genisa’s husband Yohanes Mulyadi is a Watubo colourist. Yohanes also grows cloves, but he and Genisa found weaving a better source of income.

A weaver from Watubo demonstrates resist-binding, a process of binding the yarn to create the desired motif. Photo by Andra Fembriarto

Meanwhile, on another frame, Virgensia Nurak taught me how to translate my paper study into the right proportions for resist binding — binding yarn with a tight wrapping applied in the desired pattern.

It was hard. The shape of my resist kept skewing as though it was having spasms, and I needed Virgensia to pull them back into the motif’s normal shape. We spent three laughter-filled hours together, where I only managed to bind 8cm of resist over 5cm of warp.

The next morning, Virgensia had finished binding the resist for my scarf, and it was ready for dyeing.

Rosvita explains Watubo’s commitment to vegetable dye: “Firstly, it preserves our ancestors’ cultural heritage. Secondly, it is safe for women, children, and the environment. Thirdly, it encourages us to regrow and conserve culturally important plants, and harvest them sustainably.”

Vegetable dyeing also allows weavers to experiment and be surprised by the results. “Soaking threads in experimental vegetable dye recipes makes my heart pound,” says Rosvita.

Morinda red is the trickiest colour. Threads need prepping overnight in an oily candlenut pre-mordant before colouring red. I was already breaking a sweat as I pounded the pre-mordant using a tall wooden pestle and a deep stone mortar. After that, I still had tough morinda roots to cut up and pound into a pasty dye.

When I was done, I felt like I had finished rowing cardio at the gym, but with an awestruck feeling as I watched milky white threads turn crimson with a touch of berry.

I started day three watching the vibrant threads we dyed dry in the sun. Opening the resist and rearranging the resist-dyed threads over the warp frame to form the intended motif is painstaking work.

When I finally sat at the loom, I moved the weft to and fro through the warps and watched them transform into fabric. In two hours, I weave a mere 4cm.

My emotions brimmed over the goodbye dinner. I’d always thought my urban lifestyle and career made it impossible for me to learn ikat, but Watubo made my first step in this long journey possible, immersing me in a labour-intensive process that revived our ancestors’ creative spirits.

Rosvita has been vocal about how Watubo has financially changed her life.

“I had nothing before Watubo,” Rosvita had told me during my visit. “[After Watubo] I’ve bought a house and a motorbike. I am reaching prosperity. I have everything I need.”

Other weavers have used money earned from Watubo to send their children to university, or to develop farms from which they can earn even more.

Because of this, Watubo had become a full-time livelihood for many weavers and their families, who would otherwise earn less as farmers, labourers or working for the government.

Now it’s a different story. “During the pandemic our finances haven’t been as great,” says Rosvita. “Earnings from ikat have been difficult to rely on, so weavers currently rely more on agriculture.”

The few sales that happened during the pandemic were mainly from Noesa and “very few other visitors,” mostly Flores locals. For now, Watubo has to sustain the resources to resume full production in future. “We hope this pandemic ends soon, to resume our activities and join exhibitions again,” says Rosvita.

Until then, a simple ikat mask remains to tell the rich history of this inspiring collective.

By shopping Watubo products, you support the development of Sikkanese ikat as a sustainable livelihood for Watublapi residents. To date, Watubo has worked with 25 weavers, most of whom are women under the age of 50, as well as a few men.

Supporting demand for vegetable-dyed ikat also encourages weavers to stick with dyeing processes that are safe for people and the environment, and to conserve culturally important plants such as morinda and indigo.

Supporting ikat as a sustainable profession in Watublapi would encourage their young people to stay in the village and contribute to the community. A strong ikat business also encourages other collaborations, such as working with Watublapi graduates who have left the village but whose business skills and connections to the outside world can benefit weavers.

You can find Watubo's original creations on Noesa's website. Look out also for ikat items made with fabrics from Watublapi by Noesa.

Noesa can be contacted for further enquiries about Watubo via WhatsApp at +62 81315556670.

Meet Rosvita of Watubo

Help Watubo stay on course during the pandemic

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways you can support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

Rosvita is the chairwoman of Watubo, a weaving collective in Indonesia that empowers women with sustainable livelihoods, by creating modern iterations of traditional ikat for the global customer.

“Why do we call ourselves Watubo? Watu means ‘rock,’ and bo means ‘breath’ or ‘soul.’ So Watubo means ‘breathing rock’ or ‘living rock.’ It represents our belief that no matter how hard a place home is, we will certainly survive.

Watubo strengthens this community’s bonds. Before, we just sold what we had. Now we take orders and distribute jobs so that all our weavers get their fair share.

Ikat used to be taught based on intergenerational experience. But here, we enhance it with other knowledge, market demands, and customising for designers.

Our finances improved. Some weavers have supported their children through university. I had nothing before Watubo — now I’ve bought a house and a motorbike. I am reaching prosperity. I have everything I need.

The hardest thing about teaching young weavers is patience. Teens today have phones and get distracted. I let them come around on their own terms — otherwise, I’d lose them.

But once they manage to sell their work, they start earning, they no longer need to ask for their parents’ provision, that’s when they start committing.

Likewise, our weavers are patient in teaching travellers. The goal is to have travellers understand how our ikat is made, bringing home a scarf produced with their hands-on participation, and a story to share.

I hope to retain the youth’s interest in ikat, so that the next generation would sustain Watubo. I hope young ones abroad will come home and look after our village. Even if they aren’t weavers, I hope they will develop our ikat using the knowledge and relations they gained out there.

As weavers, we don’t want our traditions pirated through printed fabrics or the mass production happening in Central Java. Our ikat bears the values of our ancestors, and our motifs tell stories of our people’s unity.

Industries wanting to produce something creative should capitalise their own ideas. Because pirating our ancestors’ heritage is the same as indirectly killing our people’s identity and livelihoods.”

Read more about Watubo here.

Support Watubo by shopping items made from fabrics created by their weavers via Noesa.

RMC Detusoko is a collective developing new opportunities to promote Lio heritage and agriculture. Through their travel venture, Decotourism, travellers can immerse themselves in the daily lives of the Lio community.

“Decotourism is about ‘travelling with purpose.’ It means minimal ecological footprint, substantial economic impact to the communities visited, and the mutual exchange of knowledge and culture. You come as a guest, and leave as family.

Our Lio identity can be summed up as lika, iné and oné: we are a people of one hearth, one mother and one house. We invite travellers to experience this through daily activities such as tending the garden, picking coffee, feeding pigs, or planting rice. Meanwhile, we also visit ancient villages, megalithic gravesites and hot springs.

Lio daily life is based on five relationships. The first is with God, which we call Du’a Gheta Lulu Wula, Ngga’e Ghale Wena Tana—Heavenly Father and Mother Earth. The others are relationships with the ancestors, nature, fellow humankind and the self.

Inspired by Joko Widodo’s 2013 presidential campaign, the idea [for RMC Detusoko] popped one evening with friends around the bonfire, and started off as a literacy movement facilitating book donations from Java to local schools here. Over time, this developed into Remaja Mandiri Community (RMC, or Bahasa Indonesia for “self-sufficient youth community”)

I spent 2014 to 2015 studying Ecotourism Management in the US, and 2016 to 2017 in Ende working as a facilitator for Swisscontact’s rural community-based tourism and solid waste management projects. During that time, I remained active with RMC, and eventually moved back to Detusoko in 2018.

My partner Eka Rajakopo and I started an English course, which children paid for by depositing recyclables in our waste bank. We had no donors, so Eka and I allocated part of our incomes to provide for RMC operations. That’s when we realised we needed a clearer direction. Hence we defined our four programmes: informal education, sustainable agriculture, social enterprise and Decotourism.

In five to ten years, I see RMC as a full-fledged training centre for local youth, and a business catering to international markets. Underlying this is the hope for our youth to return to the village and farm. Farmers are our future. It’s time for our youth to develop our own value-added products and services, and let our work do the talking.”

Read more about Decotourism

Visit RMC Detusoko

Kelimutu is more than its famed crater lakes. Travel with RMC Detusoko and immerse yourself in the agricultural heritage of Flores’ Ende-Lio highlands, and its role in the founding of modern Indonesia.

MEET THE LIO PEOPLE

“The house is our mother. The mother has an esteemed position in our society,” says Aloysius Leta, a Wologai village elder, as he shows me into his traditional house in the village.

Known for its traditional houses with its distinctive thatched roofs, Wologai is one of the oldest Lio villages in Flores’s Ende-Lio highlands. Lio people profess to be descendants of one mother and one father from Mount Lepembusu, and the Lio traditional house reflects this “one mother” narrative.

Though predominantly Catholic, much of the Lio people’s daily life are still governed by their pre-Christian customs. As such, rituals such as agricultural ceremonies, prayer offerings to ancestors, and the annual Kelimutu festival honouring ancestors are commonplace.

An invitation to enter a traditional Lio house is a sacred and intimate gesture. The veranda through which guests enter symbolises the mother’s open hands and heart, says Aloysius.

Next to the entrance is a carving of a pair of female breasts, which guests are to touch with quiet reverence upon entering. The interior of the house symbolises the mother’s womb and a communion of brotherhood.

Striking as they are, all of Wologai’s houses are reproductions of the originals — fires are a recurrent plague, and Aloysius has witnessed four Wologai fires in his lifetime. The last one in 2012 took just 15 minutes to consume every single house in the village.

“Despite these trials, we don’t run away. We remain here to guard our mother,” says Aloysius.

And it is this sense of pride and guardianship over Lio heritage that Ferdinandus “Nando” Watu seeks to preserve and share with the world through RMC Detusoko.

ONE HEARTH, ONE MOTHER, ONE HOUSE

RMC Detusoko is a collective founded by Nando and a group of young Lio farmers from Detusoko district, which encompasses Wologai, as well as Detusoko Barat, Nando’s village.

Deeply grounded in their agricultural and spiritual traditions but aware of the need to tap economic opportunities beyond their home, RMC develops the capacity of local farmers for ventures into hospitality and artisan food production — fields beyond traditional farming, but within reach with the proper support.

In 2017, RMC founded Decotourism to manage RMC’s travel venture, taking advantage of the Lio villages’ proximity to one of Ende regency’s prime attractions: Mount Kelimutu and its famed tri-coloured lakes.

With Decotourism, you take in not only the wonder of the lakes, but also the diverse ways in which young Lio farmers interpret the spirit of Kelimutu.

Revered as the final resting place of Lio ancestors, Kelimutu was once restricted as a Lio prayer ground. In the 1930s, an exiled Sukarno (also spelled Soekarno) — who later became Indonesia’s first president — used to trek here to meditate. During his exile in Ende, Sukarno became influenced by Lio philosophy, which he tapped for his vision of a decolonised, multicultural republic.

“Our Lio identity can be summed up as lika, iné and oné: we are a people of one hearth, one mother and one house.”

Nando Watu, founder, RMC Detusoko

Our visit began at 4am, where, dressed in layers to ward off the chill, we set off on a drive in pitch dark for our Kelimutu sunrise walk. Halfway through, our car pulls over. Nando steps out with a cigarette and a preparation of areca nuts, betel peppers and ground limestone.

But this isn’t a cigarette break; we are at Kelimutu’s ritual gate, the Konde Ratu prayer rock. Presenting these offerings to his ancestors, Nando prays for our travels.

We then commenced the 30-minute light trek. Initially, I needed a headlamp to light my way. But soon, the first glimmers of daylight came piercing through the velvety violet skies, and the cold receded.

A Kelimutu sunrise is like watching nature’s orchestra — the wind conducts blankets of clouds in waves over the three lakes as the landscapes change colours, accompanied by a choir of rare garugiwa, the Bahasa Indonesia name for the bare-throated whistler.

The three lakes in Kelimutu’s craters are known for changing colours, possibly due to the chemical reactions between the minerals and volcanic gases. Locals believe changes in the lakes’ colours present certain omens, and that each lake is designated different spirits: the spirits of those who died young, those who died in old age, or those who used supernatural powers for evil when they were living.

These spiritual landscapes are the foundation of RMC’s work: drawing on the philosophies of Lio identity to develop opportunities relevant to today’s world.

A FUTURE AT STAKE

A former journalist, Nando had long been interested in developing the Ende highlands’ tourism potential. In 2014, he was awarded a scholarship to an ecotourism management study programme in the United States.

On his return home, he worked as a facilitator for community-based tourism and solid waste management projects in the Ende highlands. One of his projects was Waturaka village, which won a national award in 2017 for Best Rural Ecotourism in Indonesia.

Drawing on his lessons with Waturaka, Nando, who was recently elected village head of Detusoko Barat, hopes that RMC can persuade young locals to stay home instead of venturing abroad for jobs.

“Indonesia loses up to a million farmers each year because young adults shun the farm. Although it’s good that farmers’ kids are getting higher education, it is a problem when parents establish the mindset that farmers are a low social class not worth joining.” says Nando, who is in his 30s.

“Our farmers are now typically over 45 years old, and we wonder why we’re suffering labour shortages for harvesting our otherwise profitable cloves, cocoa, rice and coffee,” he adds.

RMC seeks to show young Ende-Lio highlanders the kind of future in store for them if they choose home.

Its achievements include a partnership with Javara, a premium indigenous artisanal food brand, and participation in the British Council’s Active Citizens programme, the annual Kelimutu Festival, and exhibitions in Thailand and South Korea.

It also provides scholarship opportunities ranging from half-year tourism programmes in Bali to bachelor degrees in agriculture.

Decotourism now sees steady bookings from around the world, as well as support from Wonderful Indonesia — the state tourism authority — for participating homestays.

During our trip, we visit Waturaka, where we meet one of its ecotourism pioneers, Blasius “Sius” Leta Oja, a farmer who owns Sius Homestay. The homestay is also the rehearsal space for Nuwa Nai, a music group that handcrafts Lio instruments similar to the mandolin, flute, and violin.

Nuwa Nai performs a Lio song about the spirits of Kelimutu and for the community to stay united in a changing world, moving our driver Igen to tears.

“We are proud to preserve our culture,” says Sius. He adds that economic opportunities from performances and tour packages at Nuwa Nai keep young Waturakans home, who otherwise would migrate to work in East Malaysia’s oil palm fields.

FROM FARM TO TABLE

Back in Detusoko, we go on a scenic half-day hike, consisting of an uphill walk through vast swathes of rice fields, panoramic views at farmers’ resting huts, and moments of peaceful silence at megalithic gravesites.

The destination is Nando’s coffee plantation, where Igen and a crew of interning university students have prepared a picnic over the bonfire. After lunch, we picked ripe robusta coffee cherries and drive back with Igen.

At Nando’s house, RMC members are busy sorting the harvest with members of Universitas Flores’ agricultural faculty. Sorting is a social event filled with chatter and hot drinks, during which I learn about the different grades of robusta coffee.

Later, we taste the coffee in RMC’s Lepa Lio café, a hangout spot for Decotourism guests decorated with classic Flores details such as bamboo furnishings and palm leaf weavings.

Lepa Lio is also the production hub for RMC’s house brand, From the Fernandos’ Family Farm. Products — developed in collaboration with Javara’s food artisan academy — include peanut butter, marmalade, koro degalai (Lio for chilli-tomato relish), coffee, black rice, and sorghum.

Imelda Ndimbu, one of Lepa Lio’s employees, demonstrates how to create peanut butter — roasting the peanuts to perfection, weighing the right amounts of other locally-sourced ingredients such as sea salt and virgin coconut oil, and sterilising the jars in a hot bath.

Naturally, I bought all the jars of peanut butter we made, and then some.

Nando also makes it a point to bring his guests to shop at other social enterprises in the Ende-Lio highlands, including the Wologai coffee shop and the Sokoria farmers’ collective.

This rings true to the Lio philosophy of equal opportunity and interdependency in business; good fortune is shared with the folks of one hearth.

We end our trip with a tour of Ende city, visiting the historic sites where Sukarno drew influence from Catholic priests and Ende-Lio communities for the nation he would later found in 1945 — Indonesia.

Months later, I am still processing and learning from the memories of this eclectic trip. What lingers is the sincerity of the relationships that make the Lio identity, how these relationships promise a bright future for its young farmers, and how, not too long ago, they served as inspiration for the nation I call home.

“Come as a guest, leave as family.”

Nando Watu, founder, RMC Detusoko

Travelling with Decotourism supports sustainable livelihoods for young Lio highlanders who choose farming at home over careers in cities. Retaining well-educated, productive youth in the village promotes economic growth, cultural resilience and indigenous stewardship in the Ende-Lio highlands.

By including in your itinerary visits to cultural heritage sites such as Wologai, and activities such as the Nuwa Nai performance, you help keep alive the sacred spaces where Lio highlanders share their cultural memories.

Proceeds from Decotourism also help RMC invest in its members through higher education and career opportunities, in fields previously beyond locals’ reach, such as hospitality, artisanal food production, and enterprise.

RMC members are selected through an interview process and assigned to suitable business units. It retains 10 per cent of the rates paid for these jobs, to cover operational costs.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism was emerging as a boon to rural communities seeking to supplement their incomes while preserving their way of life. With little tourism to rely on as the coronavirus rages on, two rural communities in Indonesia are finding other ways to cope.

Can the magic of a revered water source in the Mollo highlands be felt across a virtual video tour?

Perhaps not as much as Dicky Senda would like. But with the COVID-19 pandemic shutting his hometown off from tourism revenue, such experiments provide a way to bring the sights and sounds of his hometown into people’s homes and a means to sustain his community’s way of life.

Just a little more than a year ago, Dicky had debuted the M’nahat Fe’u Heritage Trail and was looking forward to welcoming guests regularly in 2020. Run as a monthly day trip in Taiftob, South Central Timor by local collective Lakoat.Kujawas, the guided tour introduces guests to Mollo ecosystems, cuisine and narratives. Like its namesake, the Mollo Timorese m’nahat fe’u ritual, it celebrates the harvest season by serving new food.

Produce from smallholder farms showcased on the M’nahat Fe’u Heritage Trail. Photo by Andre Fembriarto

But the COVID-19 pandemic ground the heritage trail, as well as the many livelihoods it created, to a halt. While Lakoat.Kujawas cooperative members are mostly farmers who could continue with agriculture, they lost the valuable supplementary income they earned as guides and cooks for travellers. The revenue from these endeavours had also been intended to go into a collective savings programme to fund critical needs of members’ children.

Sales for their produce such as coffee, condiments and jagung bose (puffed maize for porridge) also declined, as these were sold mainly on the heritage trail. Without these sales, the farmers are vulnerable to middlemen who set prices so unfairly low that farmers often leave produce unsold — a system that creates the poverty and hunger common throughout Indonesian Timor.

“Economically we are impacted,” admits Dicky, co-founder of Lakoat.Kujawas, citing logistical problems such as closures of the postal services and sporadic operations of shuttles leaving Taiftob for the provincial capital Kupang. At one point, it took a fortnight for a package to reach Jakarta.

Nevertheless, with the help of friends, Dicky found opportunities to reinvent the heritage trail.

Enter Pasar M’nahat Fe’u (“new food market”), one of Lakoat.Kujawas’ digital initiatives. Via its social media channels, anyone in South Central Timor can now pre-order lunch boxes containing healthy, traditional Timorese dishes normally served on the heritage trail, prepared and delivered by collective members. “Our open orders promote no MSG, no palm oil, only local coconut oil, traditional dishes and recipes, and a plastic-free lunch packaged in banana leaves,” said Dicky.

Lakoat.Kujawas also debuted a digital version of the M’nahat Fe’u Heritage Trail as part of the Virtual Heritage series on the travel platform Traval.co. The free pilot was sponsored by the Indonesian Ministry of Tourism; currently it is still available for free, but participants are encouraged to "pay-as-you-wish”.

Featuring singer and activist Rara Sekar as a special guest, the virtual tour, in Bahasa Indonesia only, recreates much of the M’nahat Fe’u experience in a part-live two-hour Zoom Meeting format. Explaining the need to pre-record some portions of the tour, Dicky elaborated, “Patchy internet is a challenge: nudge your phone and you lose the signal. It’s impossible to broadcast live from the wellspring, Napjam Rock, etc.”

In the virtual format, Lakoat.Kujawas has also introduced new seasonal elements, such as a tour inside an ume kbubu traditional house, a demonstration of how jagung bose is made, and a showcase of new preserved products such as sayur asin (pickled mustard greens), guava wine, ginger beer, and roselle jam. Husband-and-wife team Willybrodus Oematan (guide) and Marlinda Nau (head cook) also presented segments of the virtual tour.

Local demand for Lakoat.Kujawas’ digital initiatives remains modest in the South Central Timor region. “But at least there is demand and it helps,” added Dicky, mentioning plans to open a Lakoat.Kujawas shop in Kupang where hot lunches can be prepared on-site and gluten-free sourdough bread and preserved goods can be sold.

In the meantime, community empowerment remains Lakoat.Kujawas’ priority. In July 2020 it restarted its Skol Tamolok learning initiative for locals, after a forced hiatus due to the pandemic. It currently offers workshops on food fermentation and preservation, documenting the local dialect, video filming and editing, and traditional music and dance.

Nando Watu, co-founder of RMC Detusoko, has spent COVID-19 on capacity-building projects for his community. Photo by Andra Fembriarto

Meanwhile in Flores, RMC Detusoko is planning for a post-pandemic comeback of Decotourism, with co-founder Nando Watu confident that tourism will recover.

RMC Detusoko is a farmers’ collective that creates opportunities for young farmers through ecotourism ventures like homestays and artisan food production, to help them diversify their livelihoods while staying grounded in their agricultural and spiritual traditions. COVID-19, however, has dampened those efforts.

“Tourism revenues are in trouble, but then tourism is a supplementary income rather than a main income for us,” says Nando, who has started serving as Head of Village Government in Detusoko Barat Village. “We are focusing on things we can do now: developing village products, creating jobs related to infrastructure, and distributing help for those who need it.”

In collaboration with the Department of Tourism and Universitas Flores, Nando is investing in capacity-building for homestay owners, guides, farmers, and other professionals so that Decotourism is ready when travellers return.

The government is also funding jobs in local infrastructure improvements such as for roads, irrigation, pools for hot springs, and villages displaying traditional homes, while providing social security to many of the villagers during the pandemic.

Nando also still occasionally handles a trickle of guests for Mount Kelimutu National Park, which currently allows a quota of 200 visitors per day with strict COVID-19 protocols, and regularly schedules fortnight-long closings for clean-ups and disinfection of indoor spaces.

But hope in physical travel does not mean not using technology to innovate. Since the pandemic, RMC has been marketing local produce to customers in Ende and Maumere via WhatsApp.

The village administration also runs a Decotourism online shop where guests can book tours in Detusoko and Kelimutu, and buy coffee and condiments. Launched in late 2020, the online shop is primarily designed for Indonesian consumers, but an English site enabling payment via major credit cards and PayPal is in the works.

Not everything in the Decotourism store is suitable for shopping; perhaps a testament to the fact that some things can only be experienced in person. And both Decotourism and Lakoat.Kujuwas stand posted to receive guests, when borders open once more.

By signing up for a Lakoat.Kujawas virtual tour, you can support the sharing and archiving of Mollo Timorese knowledge in agriculture and food preservation, as well as the continuation of their practices. This will put Lakoat.Kujawas on steadier footing to bring back community-owned sustainable tourism when leisure travel resumes.

Shopping on Decotourism’s online store would support the economic empowerment of rural communities around Mount Kelimutu, and help RMC Detusoko further its mission to dispel the stereotype that there are no sustainable economic prospects in village life.

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways you can support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

Based in Taiftob, Lakoat.Kujawas is a social enterprise that archives the cultural knowledge of Mollo Timorese through literacy, creative arts and culinary innovation.

“Middle school teachers complained to me that some of their students could hardly read. This surprised me— it was common in my 1990s childhood, but the fact that this was still the case in the mid-2010s bothered me. There are more kids now, but the quality of education and social progress here [in Taiftob] hadn’t improved.

Having worked in Kupang and Yogyakarta before, I collected books. I opened a library [in Taiftob] so that kids here can read. And I wrote a proposal telling people about my dream to build a gathering space for local children to engage in creative collaborations.

In July 2016, I was helping my father harvest loquats and guavas at the end of the season. The name Lakoat.Kujawas came to me in an instant. These fruits tug at my childhood memories. This name represents the hopes of a village child to live a better life at home, carrying the happy memories things like loquats and guavas make.

I intended Lakoat.Kujawas to cater to children. But in 2017, parents approached me. ‘Dicky, we want to join. What fun our kids are having with all these English classes, dance classes, and wonderful activities!’

I wasn’t prepared for an adult Lakoat.Kujawas, but came to understand why these parents wanted in. We, Orang Mollo, are a people of the gathering. We called our gatherings elaf. Elaf is about celebrations, coming together and fostering interpersonal relationships. It’s a moment where people meet and hear the spoken word, tales, and genealogies.

Harvest thanksgivings, and rituals held in wellsprings and rock towers make the space in which cultural knowledge is transmitted intergenerationally. When elaf is missing, the stories of our people lack the space to tell them.

I never imagined Lakoat.Kujawas becoming a travel experience. But as our work archiving our cultural knowledge came together like pieces of a puzzle, we came to realise that we have stories, values and philosophies that outsiders appreciate.

At Lakoat.Kujawas we continue to grow and nurture the spirit of solidarity and collaboration, which are increasingly scarce. Our spirit is not project-based — it’s an elaf spirit that restores our cultural spaces with dignity."

Read more about Lakoat.Kujawas

People doing good. Causes you can support. Subscribe for a weekly dose of inspiration.

Our Better World is the digital storytelling initiative of the Singapore International Foundation, which brings world communities together to do good.

Our Better World is the digital storytelling initiative of the Singapore International Foundation, which brings world communities together to do good.