A mountain getaway protecting a refuge for red pandas

Meet Shantanu

When COVID-19 put a halt to the stream of travellers who visit the far eastern Himalayas hoping to spot a red panda in the wild, one would imagine a blissful reprieve for the shy creatures.

“Actually, during the pandemic, poaching actually increased,” corrects photographer and conservationist Shantanu Prasad. “We can’t stop it all. We call the authorities. But they have weapons. We don’t.”

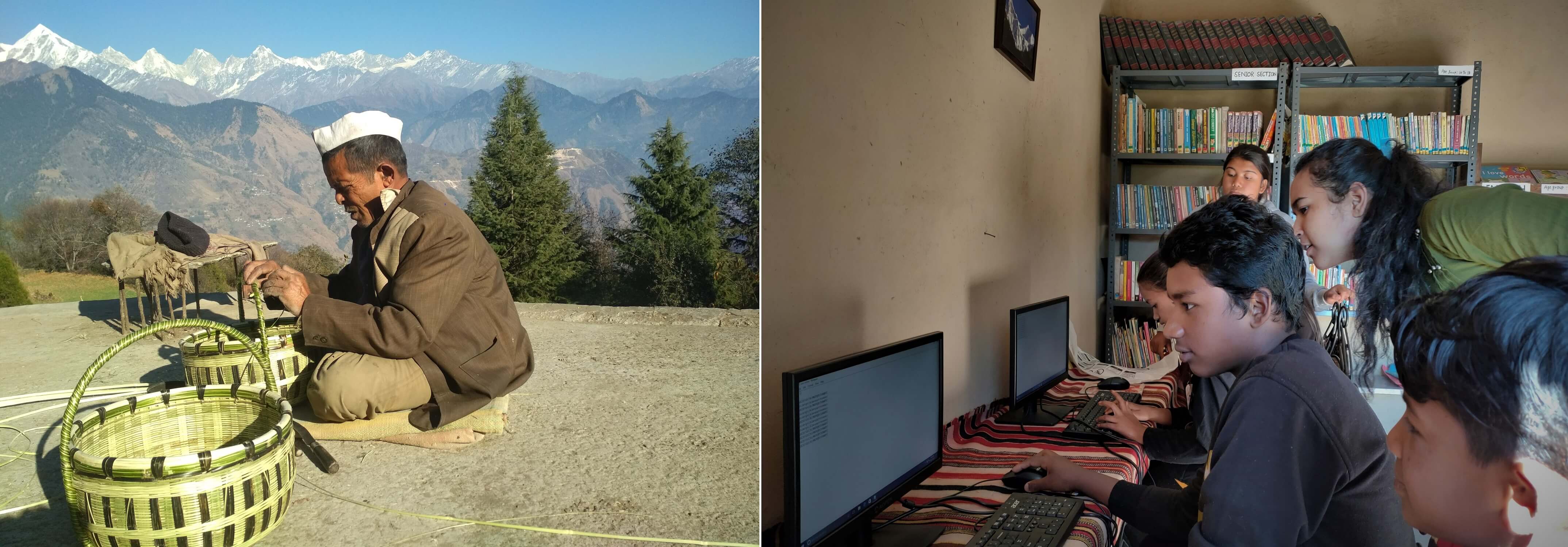

Each day, Shantanu and his team of rangers at Habre’s Nest patrol the Singalila Ridge, which straddles Nepal and India. Covering anything from 10 to 20km on foot each day, they watch out for poachers and record any sightings of red pandas, to contribute to research on these elusive animals.

But Habre’s Nest is more than just a beacon of community conservation — it is also a source of livelihoods, ensuring that some of the tourism dollars in this region benefit the local community. The rangers are also employed as hosts and guides to travellers, so that they can explore the region while minimising harm to the environment.

With travel back on the radar, Habre’s Nest hopes to see visitors again and channel funds back towards protecting the environment.

High Above The Clouds

Though daily sightings are currently reported by the Habre’s Nest team, this writer did not spot one during my three-day visit in 2019 (visitors are advised to stay a week to allow for higher chances of a sighting).

But while my expectations were high, surprisingly, I was not crushed by not seeing one. Instead, I went home enlightened by what I learnt about the tireless rangers, and thrilled by the stunning surroundings of the Singalila Ridge, which is more than just second fiddle to its famous russet-furred resident.

Stretching from central Nepal to northwest Yunnan in China, the Eastern Himalayas thread through Sikkim (India), Bhutan, the Tibetan plateau and northern Myanmar along the way. Ardent trekkers come to Singalila Ridge to complete the 50km trek from the town of Maneybhanjang to Phalut, the second-highest peak in West Bengal, India (3,595m). Others make for Sandakphu, the highest peak at 3,636m.

But for less rugged travellers, the route is also renowned as a vantage point to take in four of the world’s five highest peaks: Everest (8,848m), Kangchenjunga (8,586m), Lhotse (8,516m) and Makalu (8,485m).

An Indo-Nepali project, Habre’s Nest’s focus is on the wildlife that call the Eastern Himalayas home — protecting them and encouraging local communities to take up the mantle of conservation.

“Tourists aren’t always aware or sensitive about the forested areas they trek through and the wildlife that abounds within,” shares Shantanu, Habre’s Nest’s director

From trails being too crowded, to hikers making too much noise and leaving trash behind in the forest, “unregulated tourism”, as Shantanu puts it, is one of the biggest challenges faced by Habre’s Nest.

A Getaway for Travellers, a Refuge for Red Pandas

Habre’s Nest, which derives its name from the Nepali word for red panda, was formed by Shantanu after he learnt about the species’ endangered status.

Globally, less than 10,000 remain in the wild, living in the trees in mountainous regions. In the area earmarked for conservation by Habre’s Nest, there are just 32. An estimated 86 per cent of red panda cubs die within a year of being born; human activity is the main threat to the species.

In Singalila, the red panda’s main threats are feral dogs which may carry rabies and other diseases, and the clearing of forested land for wood and agriculture.

After identifying feral dogs as a key threat to red pandas, Habre’s Nest began holding vaccination drives for dogs with the help of animal welfare organisations, targeting dogs that belong to households as well as strays from nearby towns that follow trekkers around.

As they got to know the local community better, they realised there was a lack of medical facilities in the area. So they set up free medical camps, fostering greater trust.

This was followed by outreach sessions to create awareness of the need to protect the environment. Villagers were invited to attend training to monitor wildlife and record sightings in a 100sqkm area. Those working in the tourism sector were offered training to become more sensitive to wildlife.

When it ventured into wildlife tourism, Habre’s Nest made sure to hire only locally, ensuring that benefits from tourism stay local. “While the red panda is our flagship animal, our intention is to protect the Eastern Himalayas,” says Shantanu, who was a photographer before he became a conservationist.

Preserving the unique environment and wildlife of the area would in turn benefit locals in the long run as sustainable tourism also sustains livelihood opportunities.

Spotting Elusive Wildlife, Chasing Long-Term Goals

Catching sight of wildlife is a game of chance; after all, truly wild creatures do not show up on demand to delight travellers.

Habre’s Nest recommends staying at least seven nights for higher chances of a sighting. This includes factoring in the altitude’s unpredictable weather and a day of travel to Kaiakata, which is on the Nepal side of the ridge.

Guests do not take part in tracking red pandas; a walk to see the red pandas is only arranged when rangers spot one on patrols. Each visit lasts no more than 15 minutes.

In the meantime, guests can also spend their time at the bird hide on the premises. I was able to effortlessly pass a few hours here — clicking a few photographs every now and then of the avian company, so I could learn their names later from the in-house naturalist.

For hikers, short trek options to Kalipokhri, known for its lake with dark waters, and to Tumling, a renowned viewpoint of both Kanchenjunga and Everest, are options.

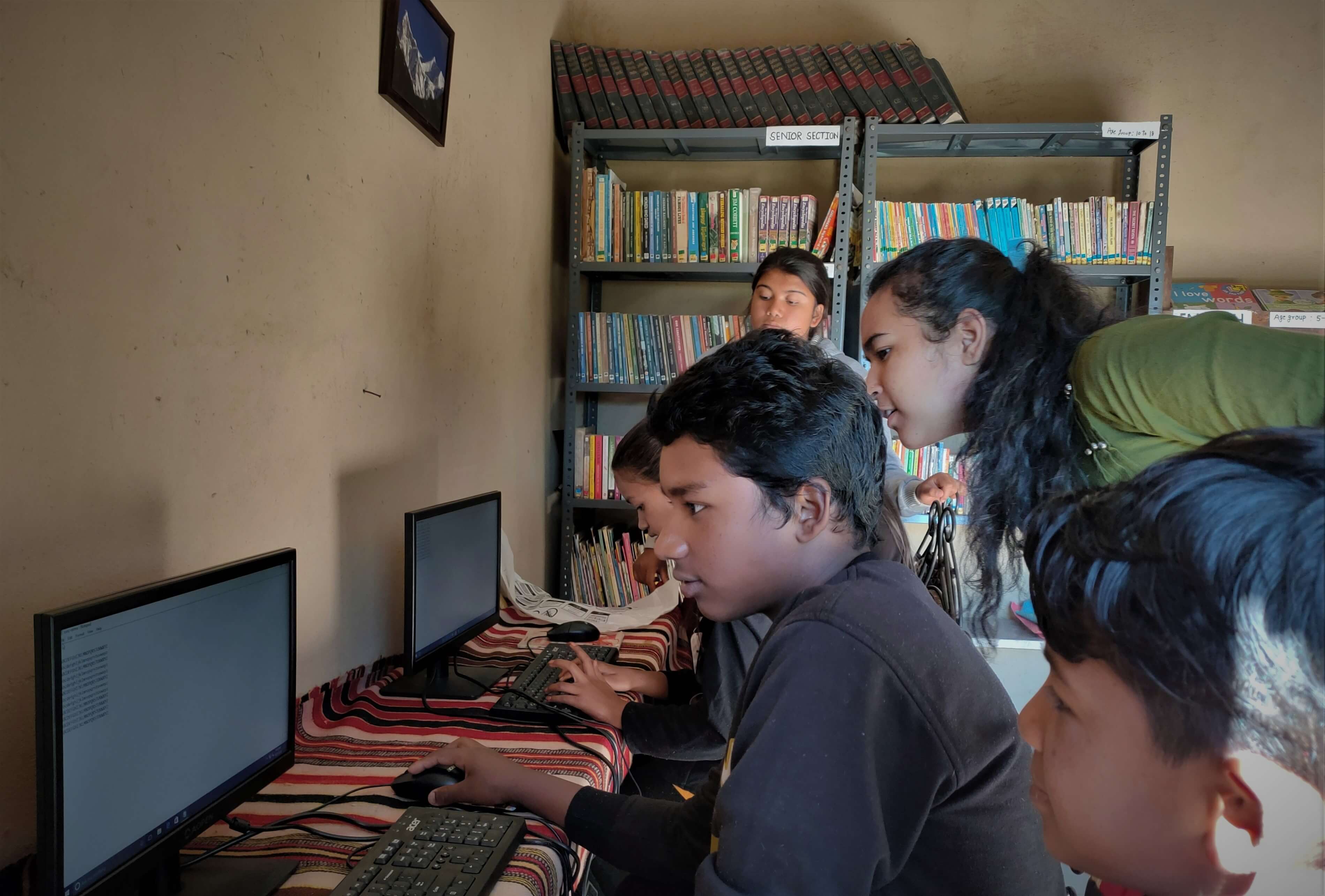

The Habre’s Nest team includes ex-poachers who now work as rangers, and double up as guides for guests, as well as manage the kitchen and homestays. Mohan Thami, a ranger at Habre’s Nest, shares, “Before, the means for livelihood were threadbare so people would set traps and poach. Today there’s awareness and a change in behaviour.”

“As trackers, we do our bit to sensitise villagers. After all, it’s because of the red panda and the training that Kaiakata has gotten visibility and sees tourists from all over the globe.”

Mohan Thami Ranger, Habre's Nest

Currently there are 11 full-time and nine part-time staff. Habre’s Nest’s lodge comprises four rooms, which can house a total of eight to 10 guests. Twenty per cent of the profits are directed towards its conservation efforts, such as local outreach on forest protection.

Shantanu notes that a comprehensive census for red pandas is currently underway, with photograph-based evidence being shared with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

“Our goal is to assign this area the status of a red panda reserve – which would aid with conservation while continuing to track and document red pandas while hosting tourists who might be inspired to do something to protect the red pandas,” he shares.

“We want to continue working with government authorities towards improved regulation within and around the national park to minimise and eventually eliminate the harm being caused by unregulated tourism.”

A visit to Habre’s Nest empowers the local community to protect the environment and the species, while uplifting local livelihoods.

In addition to hiring locals as patrol rangers and in hospitality roles, Habre’s Nest dedicates 20 per cent of its profits to its non-profit arm, the Wildlife Awareness Trust for Empowerment and Research (W.A.T.E.R.)

Even when COVID-19 hit the tourism industry hard, Habre’s Nest continued to employ its rangers to patrol the forests for poachers.Read more about Shantanu of Habre's Nest here.Read more about Mohan of Habre's Nest here.

I want to visit Habre's Nest

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways you can support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

![Yee Kuat [pictured], chairman of the village committee, takes pride in the sustainable, nature-oriented lifestyle of his community. Photo courtesy of Native. A man lifts a basket of durians to be weighed.](/sites/default/files/2023-06/GALLERY_04_YeeKuat_Durian_Credit%20Native.jpg)

![Sharing the culture of Orang Asli communities with people has been the mission of Native since 2019, when it was founded by Daniel Teoh [far right]. Photo courtesy of Native. A group of hikers cross a stream in a forest in Malaysia.](/sites/default/files/2023-06/GALLERY_07_Native%20Tours_Hiking_Credit%20Native.jpg)