Preserving palaces — and livelihoods — in a pandemic

Sometimes, as travellers, we long to be transported to a different place and time, grounded by an eye for beauty and authenticity. A longing that has only strengthened in the COVID-19 pandemic, which has bound many travellers to home.

Terrapuri Heritage Village is one such place.Nestled on a scenic slice of coast between the South China Sea and Setiu Wetlands in the Malaysian state of Terengganu, it offers the remote locale and contemporary comforts we desire from a weekend getaway, but it is no cookie-cutter resort.

Terrapuri, which means “Land of the Palaces” in Sanskrit, is modelled after an ancient Malay palace. Every building in the compound is lovingly reconstructed from old wooden houses that belonged to Terengganu royalty and noblemen centuries ago.

Behind this concept is Alex Lee, a Terengganu travel industry veteran with a deep commitment to conservation that remains even as tourism revenue takes a dive from the pandemic’s chokehold on international travel.

The Royal Treatment

When Nozirawati Rohim (Wati) first joined Terrapuri in 2015, she was amazed by what she saw. “I had never seen any place like this. Here, you really get a kampung [Bahasa Melayu for “village”] atmosphere and lifestyle,” says Wati, a general worker at the resort. “Where else in Malaysia can you find beautiful traditional houses like these [in one location]?”

Arriving at Terrapuri, guests are greeted by a gate that recalls ancient temples, which opens to a calming oasis, anchored by a sprawling courtyard with a moat, flowering plants and towering palms.Amid this lush setting are 22 resurrected guest villas restored in the style of classic Terengganu houses: each stands on a raised platform with high stilts, steep gabled roofs and a wide verandah. Beneath each house are implements like ploughs, coconut scrapers and sampans (wooden boats) — just like how kampung folks stored them in the old days.

The sense of history is carried through in the interior appointments. A gerobok (traditional wardrobe), wooden chairs, brass trays, chests and earthen jars recall homes of wealthy Malays in the olden days. Period details are faithfully recreated, right down to latches used to close windows and doors from the inside.

To construct Terrapuri, Alex began buying old houses from all over Terengganu. In 2006, he started rebuilding them house by house on a 4-ha piece of land facing the South China Sea.No expenses were spared to ensure authenticity. Because of their age – between 100 to 250 years old – most of the houses were extensively damaged or decayed. More than 50 skilled Malay artisans were hired to restore the original wooden structures and to recreate the intricate sobek (filigree) and kerawang (piercing) wood carvings. All the wooden parts were polished until they achieved the silvery sheen characteristic of their original era.

“The project ended up costing RM10 million (US$2.36 million). People called it 'Projek Orang Gila' (Crazy Man's Project).”

Alex Lee Founder, Terrapuri Heritage Village

Yet the process yielded priceless revelations. “I met so many carpenters, house owners and villagers who opened my eyes to the richness of our local heritage. If nobody champions all this, our history is in danger of disappearing,” he says.

To make the iconic Singhora clay roof-tiles — which were no longer widely manufactured — Alex tracked down the sole living craftsperson in neighbouring state Kelantan. “This kind of roof allows the house to breathe,” he shares, “but they’re also high maintenance and delicate. Sometimes, a falling mempelam (mango) can break the tile.”To put the pieces together, the ancient technique of building without using metal nails — known as pasak — was employed. Upon completion, each house was named after the village it came from and traditional rituals performed to bless them and the occupants.There was one more challenge. Who was going to run Terrapuri? Alex was advised to bring in trained hospitality specialists, but he insisted on hiring from the nearby village, although most could barely speak English and had no experience in hospitality. “This is our opportunity to empower our community,” he said.After nearly five years of planning and construction, Terrapuri finally opened its doors in 2011.

Conservation amid COVI9-19

Even with the pandemic, restoration work has continued, with all of Terrapuri’s staff employed to maintain the property, while Alex continues to hire artisans to restore houses that will eventually be part of Terrapuri.

To bring in revenue, Alex has been offering “Book Now Travel Later” deals valid till March 2022, which offer guests discounted rates for advance bookings, allowing them to contribute to preserving these architectural gems and ensuring local livelihoods even as travel is restricted.

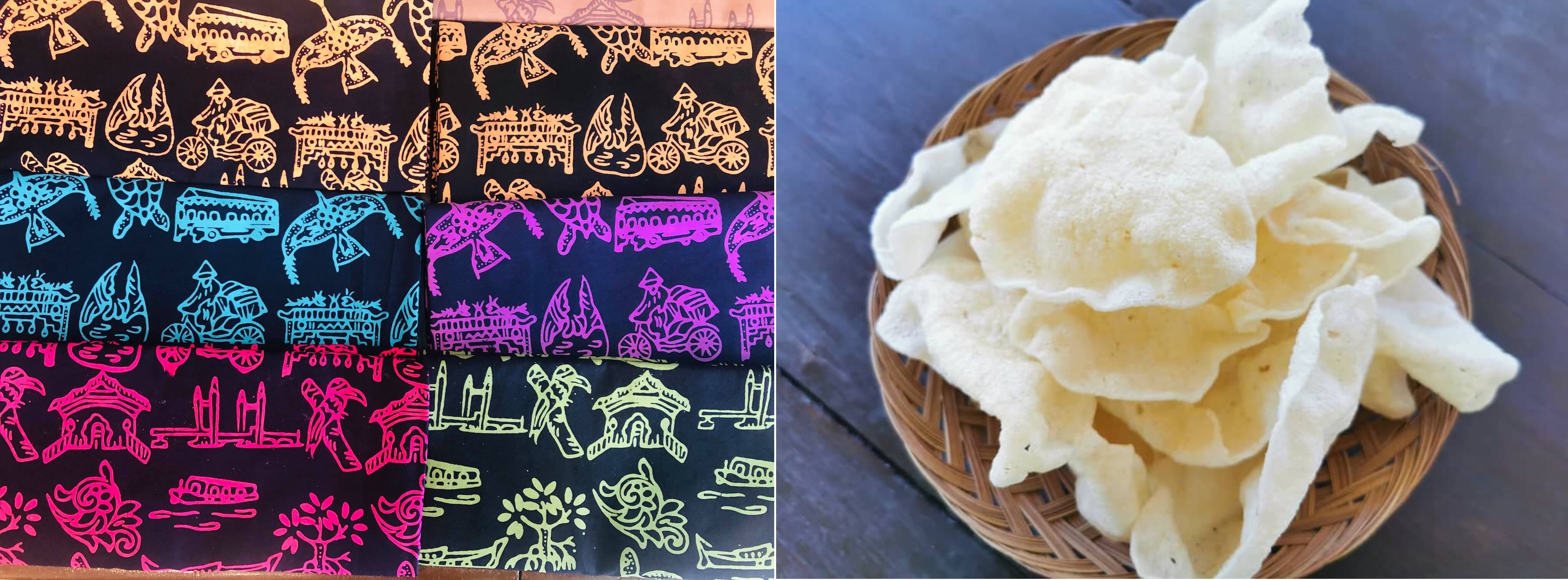

Without tourists, demand for local crafts and specialities like batik fabrics, woven baskets, and keropok keping (fish crackers) have plunged, so Alex has set up Terrapuri online stores for these products via e-tailer platforms, to help their makers develop a modest stream of income. “It’s still very new but there is some good response,” he shares.

Bestsellers include the batik sarongs and the keropok keping, a traditional Terengganu snack invented as a way to use up excess fish. Made of seasoned fish paste, these salty, crispy crackers are delicious eaten with chilli sauce, and can be bought in both raw and ready-to-eat form.

Amid the slump, there have been flowerings of interest among Malaysians for Terrapuri’s offerings; Alex has received commissions from individuals seeking classic Malay furnishings for their homes, which has provided much-needed income for the artisan communities.

“A lot of people buy furniture from Java or Bali. We want people to see the value of Malaysian lifestyle and Malay culture, and what our artisans have to offer,” says Alex. “We have a showroom now, and we will keep working on these collaborations, to bring work to our communities.”

A Heart for Heritage

Growing up, Alex was fascinated by the beauty and ingenuity of traditional Malay architecture, while immersed in the outdoors as well as local foods like budu ( fermented fish sauce) and belacan (shrimp paste).

These formative experiences came together when he ventured into the travel industry in the late 1990s, by renting out his grandfather’s shophouse in Marang town to backpackers on their way to Terengganu’s popular resort islands, dubbing it Marang Inn.

When guests asked for excursions, he engaged his fishermen friends to organise boat tours and river safaris, splitting the profits. Seeing the potential of the travel industry, he set up his own travel agency, Ping Anchorage.Marang Inn did well, earning mentions in Lonely Planet and The Guardian. But more than that, his international guests became his window to global trends and issues. From them, Alex learnt the concept of heritage conservation, a concept in its infancy in Malaysia. "Here, old wooden houses were seen as a symbol of backwardness and poverty, not as precious antiques. What was not valued by the locals was prized by foreigners,” he laments.Marang Inn was eventually demolished to make way for urban development. Seeing the same fate befall other buildings in the town, Alex realised the urgency of creating awareness about heritage preservation. Terrapuri became the project that turned this vision into reality.

It is a message that has seeped into the consciousness of those working alongside him. “When people come here, we are excited to promote our traditional food,” says Wati.

“What's the use of flying thousands of miles only to eat spaghetti? When visitors come, we must introduce them to our heritage food like ayam hikayat.”

Wati General worker, Terrapuri Heritage Village

She appreciates how Alex has been steadfast in hiring locally, unlike bigger hotels. “With stable finances, I’ve been able to gradually upgrade my lifestyle...I am thankful to Mr Lee for employing locals from nearby villages to improve their economy.”

“I hope this resort will stand strong. You need a place like this to let the next generation know about the arts and crafts of Malay culture. Nowadays, children typically stay in big cities; they only know apartments and stone houses,” she adds.

Nature's Grocer and Guardian

Tempting as it is to luxuriate in Terrapuri, venturing out rewards the intrepid traveller. A day tour of the nearby Setiu Wetlands, created by the ocean meeting coastal rivers, is a chance to encounter rare wildlife and meet the communities living there.

The richness and diversity of Setiu Wetlands is not lost on Alex, who believes that ecotourism can help protect the land while empowering those who call it home.

Though an important ecosystem that acts as a storm buffer and is home to 29 species of mammals, 161 species of birds and 36 species of reptiles and amphibians, the wetlands are under threat from uncontrolled land use. The World Wildlife Fund estimates nearly 20 per cent of Setiu’s natural vegetation was stripped between 2008 and 2011.

To increase local sensitivity towards conservation and improve locals’ livelihoods, Alex recruits fishermen as boatmen for Terrapuri’s day tours during monsoon seasons, when they do not go out to sea. With other stakeholders, he organised workshops and retraining programmes for locals to help them understand the importance of protecting their mangroves.

“If in the old days, they would simply chop down the trees to obtain wood, now they help us to replant them. They have become our eco-warriors,” Alex says with a smile.

Through Terrapuri, visitors get to meet other living legends too: “Botol Man”, a retiree who created a mini-museum from over 7,000 discarded bottles he collected from the beach; a heritage boatmaker who crafts sailing vessels for world competitions; and Pak Harun, a fisherman who can detect specific species by skin diving into the ocean and listening to fish sounds.

To support traditional Terengganu products, Terrapuri’s tours also include a visit to a village to shop for handicrafts and food items made locally from materials harvested from the wetlands.

Says Alex, “We have plenty more local legends and hidden gems yet to be discovered. The problem is that all these stories are not properly recorded. I’m hoping to get them documented someday so that at least the future generation will know.”

In 2015, local lobbyists scored a major victory when the government agreed to gazette 400 ha of the wetlands as a state park, and RM8 million was pledged to conduct eco-training for locals to manage the land.

Alex hopes the value of community-based tourism takes root, so that the people and culture can thrive, and find greater appreciation among their fellow Malaysians.

“During COVID, Malaysians cannot travel overseas, so we are seeing more Malaysian guests,” he shares. “Most of our guests came from Europe, from Singapore, but we hope to see more Malaysians appreciate what we have here, and keep the culture alive.”

Terrapuri Heritage Village is more than just a resort — it is a conservation and restoration project breathing new life into centuries-old Terengganu houses that otherwise would have been demolished or would have fallen into ruin. Saving the architecture means preserving the cultural motifs, history, folk tales and values behind it.By booking a stay at Terrapuri, you promote heritage conservation and cultural stewardship of traditional Terengganu architecture. You also provide additional stable income for the local community.

Amid COVID-19, you can make advance bookings to help Terrapuri to continue its projects and keep its staff employed, and enjoy your stay when travel restrictions are lifted.

Or consider bringing a taste of Terengganu culture to your homes — shop local crafts and snacks via Terrapuri’s online stores on Shopee and Lazada (Malaysia only).

Help Terrapuri stay the course amid the pandemic

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways you can support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

“Our history is in danger of disappearing”

Alex is the founder of Terrapuri Heritage Village, a resort that doubles as a conservation project to rescue and restore centuries-old Terengganu houses.

“I had actually been buying up old houses for years, dismantling them piece by piece, and storing them in my backyard. But only in 2006, did the perfect storm create the right conditions to build my dream resort, when I found a piece of freehold land for sale on Penarik beach.

My accountant was dismayed. He told me Penarik was not a tourist destination. I was better off investing my money in Langkawi, Bali, Phuket. I stayed firm. It must stay in Terengganu, or else it will disappear.

The project ended up costing RM10 million. It was hard to get banks to approve the project. I had to sell my properties and my cars to fund it. Some of my staff resigned because they were worried for their livelihoods. People called it ‘Projek Orang Gila’ (Crazy Man’s Project).

But the longer I worked on the project, the more I was convinced that I made the right call. From doing this, I could see the magic of the traditional houses. They are built without a single nail, using an ancient technique called pasak, so you can dismantle the structures like Lego. Imagine, this kind of innovation existed hundreds of years ago in Asia, yet we worship the West.

During construction, over 5,000 people came to see what we were building. Some, like artist Chang Fee Ming, were moved to contribute gifts: he created kisaran semangat, a unique water feature by the swimming pool that symbolises the cycles of life. Another artist created our logo, free of charge. Their encouragement motivated me to keep going.

Since opening, we’ve developed our own niche fans. This is not a place for everybody. We have more inquiries from foreigners than locals. Locals complain that it’s hot, buruk (Bahasa Melayu for “old”), dark, haunted. I joke, ‘I am a big bomoh and I will scare away all the ghosts!’ But seriously, how come you can travel to Europe and it’s okay to stay in a 600-year-old castle hotel? How do we implant into Malaysians a deeper appreciation for their identity and values?

Since completing Terrapuri, one of our carpenters has gone on to restore a RM3 million (US$710,000) museum and other houses in Sungai Lembing. Lately, the Terengganu State Government restored Rumah Haji Su, a house at Kampung Losong. Other people started buying and restoring old houses for their own collection. But we have to be careful. The problem comes when foreigners buy them and bring them back to their countries. Even we get a lot of offers.

During the process, I met so many carpenters, house owners and villagers who opened my eyes to the richness of our local heritage. If nobody champions all this, our history is in danger of disappearing.”

Read more about Terrapuri here.

Meet Wati of Terrapuri here

“Guests are like our window to the outside world”

Nozirawati Rohim is a general worker at Terrapuri Heritage Village, a resort that doubles as a conservation project to rescue and restore centuries-old Terengganu houses.

“I have been working at Terrapuri since August 2015. After my divorce, I was looking for a job and asked the cook here whether Terrapuri was hiring. I was worried because I had not worked for a while, but she told me to just come here the next day.

For me, the work here is not difficult because it’s like our housework at home. We prepare breakfast for the guests, clean the rooms, keep the surroundings tidy. The only difference is, we have to communicate frequently with foreigners using a language that’s not our mother tongue.

Initially, I felt rendah diri (Bahasa Melayu for ‘inferior') because I am not good at speaking English. If it’s local guests, I can handle. The other kakak (local ladies) told me they too were raw and inexperienced in hospitality when they arrived. They told me, ‘Don’t worry, you can learn on the job.’

I had a strong desire to try and learn. If I could excel at my job, then I can provide a good livelihood for my child.

When I started, I made a lot of mistakes. People say ‘tea time’. I say, ‘time tea’! I could understand what they wanted when they spoke to me, but when I wanted to answer, I didn’t know how to put the words in the proper order.

It took time, but my English has improved tremendously. Now I enjoy getting to know our guests and comparing their lives to ours. They are like our window to the outside world.

With stable finances, I’ve been able to gradually upgrade my lifestyle. I’ve bought a new washing machine and TV for my home. I am thankful to Mr Lee for employing locals from nearby villages to improve their economy. At Terrapuri, all the staff are locals, unlike big hotels that employ foreigners.

When I first saw Terrapuri, I was shocked. I had never seen any place like this. Here, you really get a kampung atmosphere and lifestyle.

When people come here, we are excited to promote our traditional food. What’s the use of flying thousands of miles from the West only to eat spaghetti? They can get it in their countries. When visitors come, we must introduce them to our heritage food like ayam hikayat.

I hope this resort will stand strong. You need a place like this to let the next generation know about the arts and crafts of Malay culture. Nowadays, children typically stay in big cities; they only know apartments and stone houses. Where else in Malaysia can you find beautiful traditional houses like these [in one location]?

”Read more about Terrapuri here.

Meet Alex Lee of Terrapuri here.

Stories of Good, Delivered to You

People doing good. Causes you can support. Subscribe for a weekly dose of inspiration.

Our Better World is the digital storytelling initiative of the Singapore International Foundation, which brings world communities together to do good.

Our Better World is the digital storytelling initiative of the Singapore International Foundation, which brings world communities together to do good.