'We want to eliminate the harm being caused by unregulated tourism.'

Shantanu is the director and project head of Habre's Nest, a wildlife travel enterprise on a mission to protect the red panda.

Shantanu is the director and project head of Habre's Nest, a wildlife travel enterprise on a mission to protect the red panda.

“I’ve had four years of experience in this region before we set up Habre’s Nest here in Kaiakata. Under the parent organisation Forest Dwellers, Habre’s Nest was our first project which is also rooted in sustainable tourism around rare species. While the red panda is our flagship animal, our intention is to protect the entire habitat. We undertake work where work is required but not enough is being done.

We decided to base our interventions here in Singalila because the belt extending from Nepal to the Indian states of Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh onwards to Bhutan, Myanmar, and China, is the best remaining habitat for red pandas in the wild. Singalila can be considered the epicentre of red panda distribution and could play a vital role in enabling the fragments to connect.

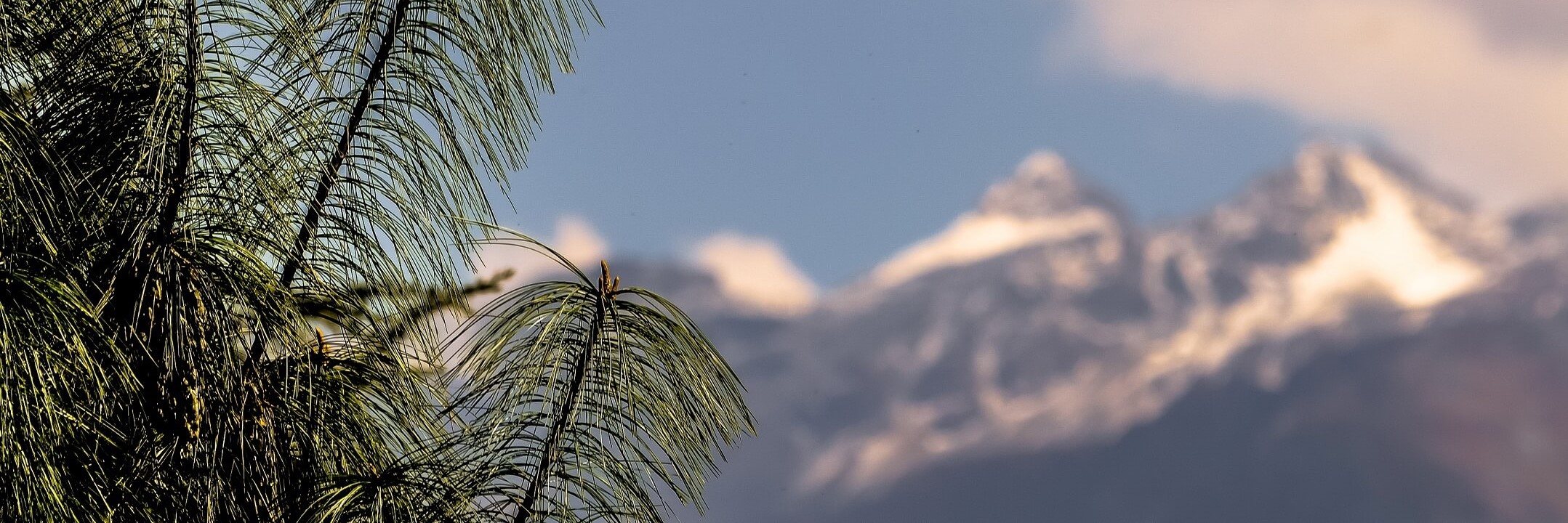

We chose Kaiakata even though the weather can be harsh at times because the views are unobstructed and it is surrounded by greenery on the Nepal and Indian side of the border which increases the probability of sighting the red panda.

We've captured more than 4,000 photographs of wild red pandas over a period of four years through tourism and achieved 98 per cent sighting of the red panda for our guests since 2016.

Our goal is to assign this area the status of a red panda reserve, which would aid with conservation while continuing to track and document red pandas and hosting tourists who might be inspired to do something on their own. We want to continue working with government authorities towards improved regulation within and around the national park to minimise and eventually, eliminate the harm being caused by unregulated tourism.”

Read more about Habre's Nest here.

When COVID-19 put a halt to the stream of travellers who visit the far eastern Himalayas hoping to spot a red panda in the wild, one would imagine a blissful reprieve for the shy creatures.

“Actually, during the pandemic, poaching actually increased,” corrects photographer and conservationist Shantanu Prasad. “We can’t stop it all. We call the authorities. But they have weapons. We don’t.”

Each day, Shantanu and his team of rangers at Habre’s Nest patrol the Singalila Ridge, which straddles Nepal and India. Covering anything from 10 to 20km on foot each day, they watch out for poachers and record any sightings of red pandas, to contribute to research on these elusive animals.

But Habre’s Nest is more than just a beacon of community conservation — it is also a source of livelihoods, ensuring that some of the tourism dollars in this region benefit the local community. The rangers are also employed as hosts and guides to travellers, so that they can explore the region while minimising harm to the environment.

With travel back on the radar, Habre’s Nest hopes to see visitors again and channel funds back towards protecting the environment.

Though daily sightings are currently reported by the Habre’s Nest team, this writer did not spot one during my three-day visit in 2019 (visitors are advised to stay a week to allow for higher chances of a sighting).

But while my expectations were high, surprisingly, I was not crushed by not seeing one. Instead, I went home enlightened by what I learnt about the tireless rangers, and thrilled by the stunning surroundings of the Singalila Ridge, which is more than just second fiddle to its famous russet-furred resident.

Stretching from central Nepal to northwest Yunnan in China, the Eastern Himalayas thread through Sikkim (India), Bhutan, the Tibetan plateau and northern Myanmar along the way. Ardent trekkers come to Singalila Ridge to complete the 50km trek from the town of Maneybhanjang to Phalut, the second-highest peak in West Bengal, India (3,595m). Others make for Sandakphu, the highest peak at 3,636m.

But for less rugged travellers, the route is also renowned as a vantage point to take in four of the world’s five highest peaks: Everest (8,848m), Kangchenjunga (8,586m), Lhotse (8,516m) and Makalu (8,485m).

An Indo-Nepali project, Habre’s Nest’s focus is on the wildlife that call the Eastern Himalayas home — protecting them and encouraging local communities to take up the mantle of conservation.

“Tourists aren’t always aware or sensitive about the forested areas they trek through and the wildlife that abounds within,” shares Shantanu, Habre’s Nest’s director

From trails being too crowded, to hikers making too much noise and leaving trash behind in the forest, “unregulated tourism”, as Shantanu puts it, is one of the biggest challenges faced by Habre’s Nest.

Habre’s Nest, which derives its name from the Nepali word for red panda, was formed by Shantanu after he learnt about the species’ endangered status.

Globally, less than 10,000 remain in the wild, living in the trees in mountainous regions. In the area earmarked for conservation by Habre’s Nest, there are just 32. An estimated 86 per cent of red panda cubs die within a year of being born; human activity is the main threat to the species.

In Singalila, the red panda’s main threats are feral dogs which may carry rabies and other diseases, and the clearing of forested land for wood and agriculture.

After identifying feral dogs as a key threat to red pandas, Habre’s Nest began holding vaccination drives for dogs with the help of animal welfare organisations, targeting dogs that belong to households as well as strays from nearby towns that follow trekkers around.

As they got to know the local community better, they realised there was a lack of medical facilities in the area. So they set up free medical camps, fostering greater trust.

This was followed by outreach sessions to create awareness of the need to protect the environment. Villagers were invited to attend training to monitor wildlife and record sightings in a 100sqkm area. Those working in the tourism sector were offered training to become more sensitive to wildlife.

When it ventured into wildlife tourism, Habre’s Nest made sure to hire only locally, ensuring that benefits from tourism stay local. “While the red panda is our flagship animal, our intention is to protect the Eastern Himalayas,” says Shantanu, who was a photographer before he became a conservationist.

Preserving the unique environment and wildlife of the area would in turn benefit locals in the long run as sustainable tourism also sustains livelihood opportunities.

Catching sight of wildlife is a game of chance; after all, truly wild creatures do not show up on demand to delight travellers.

Habre’s Nest recommends staying at least seven nights for higher chances of a sighting. This includes factoring in the altitude’s unpredictable weather and a day of travel to Kaiakata, which is on the Nepal side of the ridge.

Guests do not take part in tracking red pandas; a walk to see the red pandas is only arranged when rangers spot one on patrols. Each visit lasts no more than 15 minutes.

In the meantime, guests can also spend their time at the bird hide on the premises. I was able to effortlessly pass a few hours here — clicking a few photographs every now and then of the avian company, so I could learn their names later from the in-house naturalist.

For hikers, short trek options to Kalipokhri, known for its lake with dark waters, and to Tumling, a renowned viewpoint of both Kanchenjunga and Everest, are options.

The Habre’s Nest team includes ex-poachers who now work as rangers, and double up as guides for guests, as well as manage the kitchen and homestays. Mohan Thami, a ranger at Habre’s Nest, shares, “Before, the means for livelihood were threadbare so people would set traps and poach. Today there’s awareness and a change in behaviour.”

“As trackers, we do our bit to sensitise villagers. After all, it’s because of the red panda and the training that Kaiakata has gotten visibility and sees tourists from all over the globe.”

Mohan Thami Ranger, Habre's Nest

Currently there are 11 full-time and nine part-time staff. Habre’s Nest’s lodge comprises four rooms, which can house a total of eight to 10 guests. Twenty per cent of the profits are directed towards its conservation efforts, such as local outreach on forest protection.

Shantanu notes that a comprehensive census for red pandas is currently underway, with photograph-based evidence being shared with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

“Our goal is to assign this area the status of a red panda reserve – which would aid with conservation while continuing to track and document red pandas while hosting tourists who might be inspired to do something to protect the red pandas,” he shares.

“We want to continue working with government authorities towards improved regulation within and around the national park to minimise and eventually eliminate the harm being caused by unregulated tourism.”

A visit to Habre’s Nest empowers the local community to protect the environment and the species, while uplifting local livelihoods.

In addition to hiring locals as patrol rangers and in hospitality roles, Habre’s Nest dedicates 20 per cent of its profits to its non-profit arm, the Wildlife Awareness Trust for Empowerment and Research (W.A.T.E.R.)

Even when COVID-19 hit the tourism industry hard, Habre’s Nest continued to employ its rangers to patrol the forests for poachers.Read more about Shantanu of Habre's Nest here.Read more about Mohan of Habre's Nest here.

I want to visit Habre's Nest

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways you can support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

Mohan is a tracker at Habre's Nest, a wildlife travel enterprise on a mission to protect the red panda.

“I am from Maneybhanjang and have been associated with Shantanu and Habre’s Nest from the beginning. I’ve been a part of this initiative from when we were building this homestay ground up in 2016. Today, as a tracker who supports conservation, I earn enough to support my family.

Before, I didn’t understand anything or know enough about the red panda, even though I, like many others, would see them. Now, I understand the need for conservation and the value it adds to the biodiversity here. I understand better some of the behaviour of the red panda from having been able to observe it in its natural habitat.

Until a few years ago, the means for livelihood within and around these villages here were threadbare so some people would set traps and poach red pandas to sell the fur on the black market or sell the animal itself as a pet.

Today things are a lot different. There are laws prohibiting and penalising poaching. But there’s awareness and a change in behaviour too. Employment opportunities exist, thanks to the booming tourism.

As trackers, we do our bit to sensitise villagers every day. After all, it’s because of the red panda and these sensitisation trainings that Kaiakata has gotten visibility on the map and sees tourists from all over the globe.

Quite naturally, it has also brought competition and envy from peers within the tourism sector here. There have been instances when rumours are spread and Habre’s Nest gets wrongly accused, including that we keep red pandas inside the property. which is obviously ridiculous. Some things will need more time to change, I guess.”

Read about Habre's Nest here.

Photo courtesy of Shantanu Prasad

For Sanju Negi, life has come full circle.

From opposing the creation of a national park in the western Himalayas — on grounds that it would destroy locals’ ability to live off the land as they have traditionally — Sanju is now a custodian of the park’s natural environment.

First, recognising the potential of eco-tourism, he became a trekking guide and member of a cooperative committed to responsible tourism in partnership with Himalayan Ecotourism, a travel social enterprise.

Now, with tourism income drastically fallen as a result of COVID-19, Sanju has joined hands with Himalayan Ecotourism to tap the power of carbon offsetting: allowing people all over the world to offset their carbon footprint by planting trees in the Himalayas.

With its never-ending pine and cedar forests, flowing streams and waterfalls, and snow-capped peaks rising grandly above it all, Tirthan Valley, which is part of the Great Himalayan National Park (GHNP), is the postcard-perfect destination travellers dream of.

Himalayan Ecotourism grew out of a desire to divert the benefits of tourism towards the valley’s communities, for whom the creation of the park in 1984 had signalled loss.

Many villagers had depended on the medicinal herbs and forest produce they foraged as a source of income, while the land was also important grazing ground livestock. “As locals, many of us were opposed to the national park because it cut off our right to the forest and our livelihood had depended on it,” says Sanju.

With tourism taking off in the region, Stephan Marchal, a Belgian who had worked on sustainable development projects in India, hatched the idea of an ecotourism cooperative owned and managed by locals.

In 2014, he co-founded Himalayan Ecotourism, a joint venture with the GHNP Community-Based Ecotourism Cooperative, which comprises local guides who are also shareholders. Stephan handles management and marketing needs, while guides like Sanju — who is also the treasurer of the cooperative — take turns to lead treks, from which they keep 60 per cent of the revenue.

“I was opposed to the model of ecotourism where locals are mere daily wage labourers while the business was owned by somebody else. From the beginning I was sure I wanted to develop and grow the business in the right way,” says Stephan.

Himalayan Ecotourism’s philosophy of inclusion, not exclusion, also extends to its guests. While the conventional image of trekking is one of outdoor gear ads filled with lean and fit-looking individuals, Himalayan Ecotourism also organises trips for guests with mobility problems, such as older hikers or people with disabilities.

The trips range from forest bathing — camping in the wild and immersing oneself in nature — to nine-day treks, aided by equipment and specially-trained guides to ensure comfort and safety.

In 2019, Himalayan Ecotourism won not one but two of the Indian Responsible Tourism Awards instituted by Outlook Responsible Tourism.

In early 2020, COVID-19 began its sweep around the world, bringing global travel to a halt and devastating communities that had depended on tourism for their livelihoods.

Himalayan Ecotourism was not spared, with business plunging to zero overnight. “We had to find alternate sources of income for our cooperative members,” shares Stephan.

The response was one that would not only provide relief income to its members, but also expand on its eco ethos: a reforestation programme implemented by members which would repair land damaged by overgrazing, logging, and fires, supported by anyone who wishes to offset their carbon footprint.

For example, someone making a return trip between Paris and Delhi by air will incur around 1,680kg in carbon emissions. To offset this, three trees will need to be planted and maintained for 40 years (Himalayan Ecotourism’s calculations are based on a tree removing an average of 15kg of carbon emissions from the air annually over 40 years).

Through Himalayan Ecotourism, individuals can buy carbon credits, the proceeds of which will be used to plant and maintain the trees for a minimum of 20 years. Customers will be given periodic updates, including geotag-enabled reports.

Although members would not earn as much from replanting efforts as they did from tourism-linked activities, they saw the long-term benefits in reforesting the land.

Over a telephone call, Sanju, who was the first to suggest replanting trees in the eco zone, shares: “There have been a few COVID-19 cases around here. The lockdown changed things for us overnight but between the reforestation project and some work on our own farms, we’ve mostly been able to manage making ends meet.

“We spent a bulk of our time during the monsoon season replanting mostly deodar (Himalayan cedar), silver oak, apricot, and a few persimmon varieties. We will undertake a similar replantation drive during the winter and continue along the treeline in Pekhri.” In a challenging situation that might have seen them slipping into despair and frustration, Sanju notes that these activities helped keep them engaged and contributing to their communities.

With the future of tourism uncertain, the reforestation programme is Himalayan Ecotourism’s main avenue of providing a sustained, non-charity-based source of income to its cooperative members, and to “mobilise and strengthen the capacities of the local communities”. Over 1,000 trees have been planted so far in a 2 sq km area around Pekhri village.

Keeping true to its philosophy of community ownership, Himalayan Ecotourism has also mobilised women from and around Pekhri on a voluntary basis to manage the reforested areas.

They are also being encouraged to organise themselves into self-help groups and set up microenterprises such as traditional kullu shawl making and bee-keeping. Himalayan Ecotourism will provide marketing support for the self-help groups and will share the initial capital costs.

And for children aged eight to 12 years old, Himalayan Ecotourism is offering free basic English speaking and computer skills, taught by two local women who will be paid a stipend for their work.

Over my four days in the GHNP with Himalayan Ecotourism in October 2019, I learnt about the power of involving locals as shareholders in sustainability initiatives, turning them into conscious stewards of their land.

Then, Sanju had shared his pride in Himalayan Ecotourism’s progress and the role of ordinary community members in achieving it. “It has been the ones most in need, the ones without any stable income or alternate means, who’ve given it their most,” he said.

This community spirit is something Stephan hopes will live on as Himalayan Ecotourism navigates a “new normal”. “On the one hand, we will remain a local organisation organising treks and other activities in the national park, and on the other hand, we will be a regional organisation (Himalayas) who will be able to implement bigger projects for conservation,” he says.

He is hopeful that tourism will return to the valley, though he stresses that safety and wellbeing of the entire community comes first.

“The takeaway from the experience of the past eight months has been that it wouldn’t be wise to continue having all our eggs in the same basket. Tourism-based livelihoods are and will remain one of many avenues to support the local community, but we will continue to build on diversifying our approaches and efforts,” he says.

Himalayan Ecotourism, through its cooperative model, engages locals as shareholders — and not as passive workers — with a two-fold agenda: a) a means to livelihood, and (b) as conservators of a fragile ecosystem that has been experiencing the side-effects of human activity.

When you travel with Himalayan Ecotourism, you not only ensure that money from tourism in the region empowers locals who are dedicated to protecting the land they call home but can also opt-in to neutralise your own carbon footprint.

Meet Stephan of Himalayan Ecotourism, and Sanju of the GHNP Community-Based Ecotourism Cooperative, which works with Himalayan Ecotourism to improve livelihoods through eco-tourism and sustainability initiatives.

Help Himalayan Ecotourism stay the course amid the pandemic

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways to support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

Two years ago, I spent a few days with members of the Akha tribe in the hills of northern Thailand, vegetable-picking in the jungles, enjoying a traditional meal in bamboo over open fire, and learning about their culture and traditions. Organised by social enterprise Local Alike, it introduced me to the concept of sustainable, community-based tourism aimed at empowering indigenous peoples.

Unfortunately, tourism came to a sudden halt during the COVID-19 outbreak. Many of Local Alike’s community partners saw their tourism revenue plunge — by about 10 million baht (approximately US$300,000) — with little recourse to alternative income sources. This put the very concept of sustainability to the test.

The solution? Bringing a taste of the hill tribes to city doorsteps, through a new food delivery service.

Local Aroi, which was set up by Local Alike to offer food experiences (aroi means “delicious” in Thai), launched Local Aroi D in Bangkok, a delivery service offering meals made from ingredients sourced from Local Alike’s hill tribe partners, to generate income for them.

The new initiative was a more than palatable solution, tapping on the tribes’ culinary strengths and the rising demand for food delivery due to people working from home amid a lockdown in Thailand. “Bringing food from the community to the platform, we built it for the reason that not every local community was successful in tourism,” adds Local Alike founder and CEO Somsak Boonkam.

Rawimon Mongkolthanapoom, who goes by Keaw, is Akha, from the Pha Mee region — one of the 15 communities who came onboard the initiative.

“There were no tourists and most shops were closed. So the community had to find an alternative way, and they distributed fruits such as lychees, oranges, and so on,” says Keaw. “We had to help farmers in our community to make income instead of relying solely on tourism. Local Aroi also supported our community by using our local ingredients to prepare their dishes.”

So far, about 1.8 million baht (US$57,000) has been directed back to the local communities, while community members have been hired for “chef’s table” experiences. Though the initiative ended in September, Local Alike plans to bring it back in future, while continuing to explore chef's table experiences.

The initiatives are creating new awareness and appreciation of the tribes’ culinary traditions. Recipes handed down from generations like deep fried spring rolls Khlong Toei-style and kanom-tarn (or palm sugar cake) from Baan Pa Nong Khao, are given a fresh twist for events. Akha-style chilli paste, known as a palachong, is reinvented into a spaghetti dish [pictured below] available for delivery on Local Aroi D.

For Keaw, the experience is ultimately “more about culture-sharing and building awareness”. The hill tribes are proud of their abundant land and resources, and are eager to share it, she explains, but for years, they have had to bear with unwelcome notoriety from the region’s history as a trade route for opium.

Though culinary exchange, Keaw is keen to move on from these outworn tales and help visitors see her people through a fresh lens. Sharing that her favourite meal is ku chi lu — crispy pork belly stir-fried with rakshu root — Keaw explains that rakshu is a local herb in the Akha kitchen that enhances taste. Although all parts of the plant are edible, the root is the most popular because of its crispy texture when cooked, and it is said to have anti-cold properties and helps reduce cholesterol.

![Keaw getting ready to showcase the culinary gems of the Akha tribe [left]. She hopes that interest in northern Thailand cuisine creates more interest in the country’s indigenous cultures. Photo from Local Alike](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Webp.net-compress-image_0.jpg)

The effects of COVID-19 have been dire, but it has also piqued the interest of Thais in the diversity of the culture within the country beyond their own. Through platforms like Facebook Live and Zoom, it has organised well-received virtual village tours in Thai, such as “From Local Chefs to Local Aroi” with Baan Luang Neau in Chiang Mai and Baan Khok Mueang in Buriram. Another virtual event, “A Mother Teaches Her Sons to Cook”, brings a new breed of audience-diners along on gastronomical adventures while sourcing local ingredients and re-creating recipes.

With the Thai government encouraging domestic tourism, the hope is that the interest in hill tribe cuisine will eventually lead people to visit the region in person. “We brought local food to people in the central region who haven’t yet had the opportunity to visit Pha Mee. We present these fabulous experiences from special dishes using authentic community ingredients. When tourists finally visit Pha Mee, they are familiar that this is its local dish,” says Keaw.

Somsak holds a warm hope for this relationship with the indigenous communities to continue and to see the Local Aroi brand evolve into one that brings local traditions to the global stage. “It should be the centre of the community's signature recipes,” he says. “I will do my part in bringing these conversations to the dinner table - till the flight paths open up and I get the opportunity to recapture the flavours of Thailand’s hill tribes.”

Local Alike was one of the winners of Singapore International Foundation’s Young Social Entrepreneurs programme in 2014. Through mentorships, study visits, and opportunities to pitch for funding, the programme nurtures social entrepreneurs of different nationalities, to drive positive change for the world.

If you live in Bangkok, consider ordering a meal from Local Aroi D, and look out for pop-up dining experiences featuring menus inspired by hill tribe cuisines. Your order will support the tribes supplying the ingredients for these meals, the chefs hired from local communities to prepare these meals, as well as promote more awareness of the respective tribes’ cultures.

When travel resumes, consider booking a trip with Local Alike. By exploring communities like Suan Pa and Pha Mee through Local Alike, you help to support responsible tourism led by the local community members, and fuel sustainable livelihoods. It also helps to foster cultural exchange and encourage the preservation of traditions. As of 2019, Local Alike has worked with 100 villages in 42 provinces and created over 2,000 part-time jobs.

Read about our trip in 2018 for more inspiration.

Help Local Alike stay the course amid the pandemic

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways to support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

Stephan is Managing Director of Himalayan Ecotourism, an inclusive trekking agency that works with a local cooperative to ensure fair livelihoods and ownership for locals.

“It started when I’d informally organised a trek for a few Belgian friends and learnt about the loss of local livelihoods from the prohibition of access to forest produce within the Great Himalayan National Park.

As many of the locals would also double up as guides and porters during the trekking season in Tirthan Valley, ecotourism emerged as a viable option for an alternate source of income. But I was opposed to the model of ecotourism where locals are mere daily wage labourers while the business was owned by somebody else.

I wanted to earn, but I also wanted the people to grow with me. So, after consulting with locals who showed interest and willingness to come together, the GHNP Community-Based Ecotourism Cooperative was registered in July 2014.

As a company, we have faced a lot of resistance from non-members. It became my responsibility to ensure that the cooperative made business and the members received an income. But there were rumours that I took all the money! Our financial records are transparent, templatised and easy to understand. A significant portion of what is charged to our guests goes towards the guide team while another portion is split between equipment maintenance and overhead costs. The profit is equally shared between the cooperative and my firm, which manages the marketing needs.

In recent times, the rising popularity of Tirthan Valley has not only seen an overcrowding of tourists but also rampant mushrooming of guesthouses and homestays. Not all the properties belong to locals. However, not all properties belonging to locals are constructed in the traditional, earth-friendly manner either. There are locals who are eager to give up their land on lease and earn a passive income that meets their everyday needs.

[In the COVID-19 pandemic], we [have] had to find alternate sources of income for our cooperative members.

On the one hand, we will remain a local organisation organising treks and other activities in the national park, and on the other hand, we will be a regional organisation (Himalayas) who will be able to implement bigger projects for conservation.

The takeaway from the experience of the past eight months has been that it wouldn’t be wise to continue having all our eggs in the same basket. Tourism-based livelihoods are, and will remain one of many avenues to support the local community, but we will continue to build on diversifying our approaches and efforts.”

Meet Sanju of the GHNP Community-Based Ecotourism Cooperative

Read more about Himalayan Ecotourism

Sanju is the treasurer of GHNP Community-Based Ecotourism Cooperative, which works with Himalayan Ecotourism to empower locals and grow sustainable tourism.

“As locals, many of us were opposed to the national park because it cut off our right to the forest and our livelihood had depended on it.

It was also the start of tourists and researchers starting to trickle in this region. A few years down the line, I met Stephan when he was talking about forming a cooperative. To me it seemed like a reasonable way to carry out a business and so I joined.

In the beginning, we would enrol anyone and everyone who was interested as a member of the cooperative. But it has been the ones most in need – the ones without any stable income or alternate means – who’ve given it their most.

All our trekking guides have to complete their training from a mountaineering institute. It’s very risky otherwise – even for us as a business, the reputation is at stake.

I had accompanied Keshavji and Stephan to New Delhi after Himalayan Ecotourism had been shortlisted for the Indian Responsible Tourism Awards by Outlook Responsible Tourism.

Receiving two awards, both of which came to us as a surprise, in a room filled with the who’s who from the tourism sector was not only an honour, but the greatest recognition to date of what we, as a unit, not individuals, had been able to achieve in spite of the hardships and the resistance from local elite.

The lockdown changed things for us overnight but between the reforestation project and some work on our own farms, we’ve mostly been able to manage making ends meet.

We spent a bulk of our time during the monsoon season replanting mostly deodar (Himalayan cedar), silver oak, apricot, and a few persimmon varieties. We will undertake a similar replantation drive during the winter and continue along the treeline in Pekhri.”

Meet Stephan of Himalayan Ecotourism

Read more about Himalayan Ecotourism

Help Batu Batu stay the course amid the pandemic

A fantasy beach holiday may go like this: your boat cruises to a stop, bobbing gently over crystal-clear turquoise waters. You step onto soft white sand, and lush palm trees form a chorus line to welcome you to your tropical getaway.

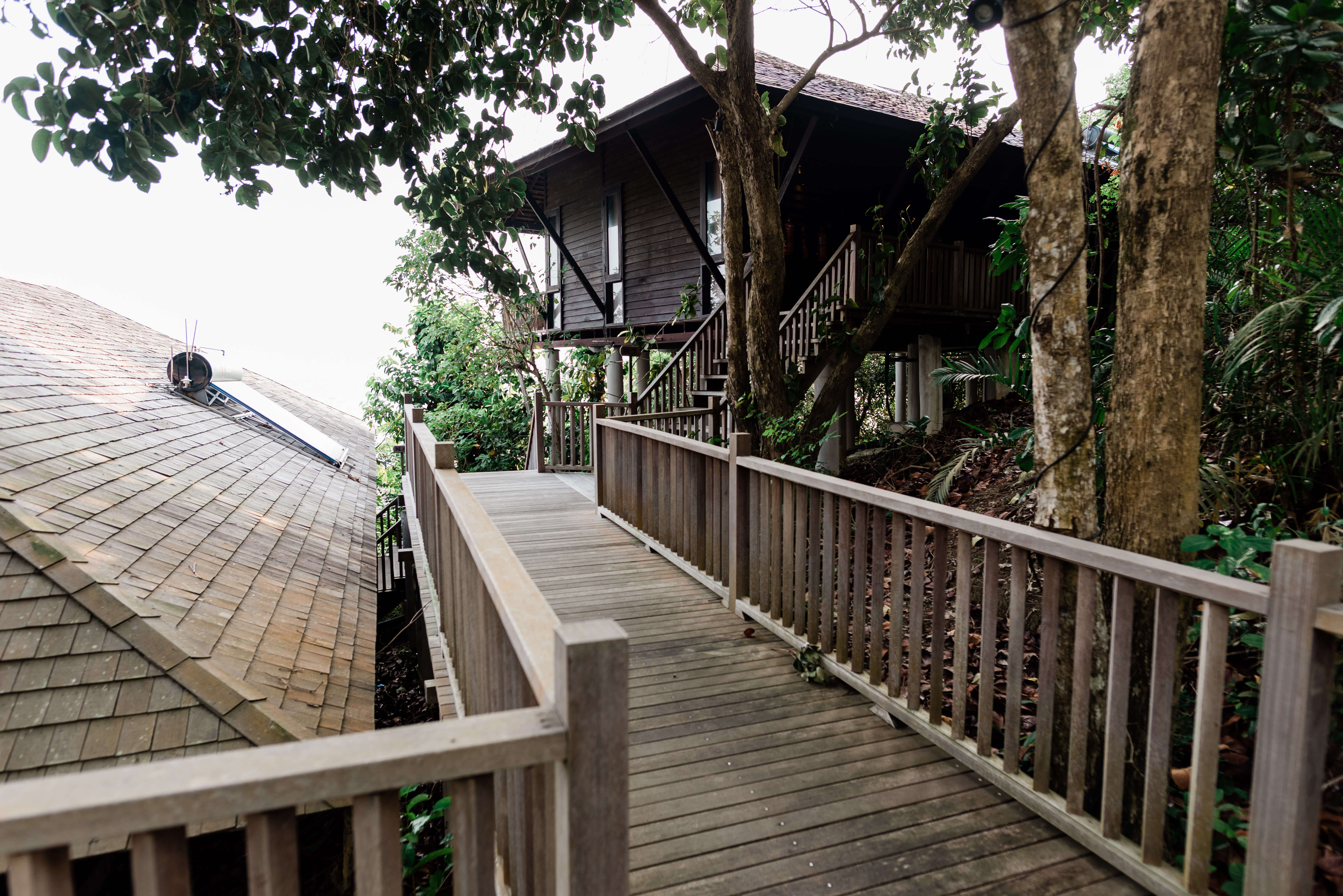

As the only resort on Tengah Island off the coast of Johor, Batu Batu’s wooden villas and eight private beaches indeed fulfils this sunseeker’s dream.

But this isn’t just another good-looking holiday destination. This pristine piece of paradise in the South China Sea also serves as a refuge for endangered green and hawksbill turtles, a centre for environmental conservation and a model of responsible tourism.

Upon alighting at the resort jetty, we had barely taken 10 steps before being drawn to the shimmering seawater teeming with schools of needlefish. A few good minutes passed before we noticed all our fellow boat passengers were still hanging around the jetty, similarly transfixed by the view.

We eventually start strolling towards the villas, shaded by a canopy of coconut, bamboo and palm trees swaying gently in the breeze. I pause (again) for a closer look at the crystal-clear waters, which was when I spot large patches of seagrass and coral reefs – the first hint that a rewarding snorkeling experience awaits at Batu Batu.

As I settle into the spacious villa, I find a copy of the resort’s Green Guide on the coffee table, detailing Batu Batu’s environment and conservation initiatives. It also notes that the reefs surrounding Tengah Island are home to diverse marine life: critically-endangered hawksbill turtles, endangered green turtles, black tip reef sharks, clownfish, barracuda, moray eels, blue-spotted stingrays and more. Occasionally, some dugongs even swim by for a visit.

Such abundant marine life is not something Batu Batu takes for granted, which is why its Co-founder and Managing Director Cher Chua-Lassalvy advocates a “tread lightly” approach in running the resort.

Her care for the environment stems from a personal place, as Tengah Island used to be Cher’s family’s private retreat for close to 15 years. Her father, who bought the property “out of love at first sight”, was happy to keep things as they were.

So in 2009, when her father proposed that they start a resort, protecting the natural beauty of a place they love was a priority.

Johor Marine Park — in which Tengah sits, together with popular island destinations like Pulau Rawa and Pulau Besar — has been affected by human activity such as illegal poaching, reckless anchoring and pollution over the years, causing reef health and marine life to decline.

As such, the resort has been designed to limit negative impact from human activity. “We went from wanting to make sure we didn’t spoil the place by opening something here, to realising after a few years that our presence here meant that some things improved instead,” she shares.

For example, the coral reefs became healthier once boats were no longer allowed to anchor in the area in front of the resort, and turtles also returned to nest on the beaches.

“Because we’re here, poachers no longer come onto the resort’s beaches – whereas on uninhabited islands there is less to stop them,” says Cher.

“It started as ‘We don’t want to destroy the island’… and became ‘Can we actually regenerate it?’”

Cher Chua-Lassalvy Co-founder and Managing Director, Batu Batu

In 2017, Batu Batu founded Tengah Island Conservation (TIC), a non-profit “biodiversity management initiative” to focus on research, rehabilitation and regeneration of the island’s natural environment.

Profits from the resort provide core funding for TIC, which has a team of five full-time marine biologists and environmental scientists stationed on the island. Since TIC began reef restoration efforts, it has seen reefs in its nursery grow up to 5cm per month.

We were listening intently to one of TIC’s Turtle Conservation Talks for resort guests, when we heard excited exclamations — TIC had just excavated a batch of late-to-hatch baby turtles, and were about to release them.

Cue a dozen adults running out to witness this rare sight, and cheering on each tiny hatchling in their race to the sea.

The sea turtle hatchery was set up in 2015 to prevent turtle nests being poached — for sale and consumption — from the back of the island. Today, to protect even more nests, the TIC team conducts daily morning and night boat patrols around the seven neighbouring islands as well.

Between 2015 to 2019, TIC managed to protect 254 nests from poachers and predators, and released 17,581 endangered green and hawksbill turtle hatchlings into the ocean.

After the last tiny turtle found the way to its swim debut, TIC Outreach Coordinator Mohammed Alzam, who was conducting our talk, shares that watching hatchlings being released to sea never gets old – and is in fact, his favourite sight on the island, followed by the black-tipped reef sharks, a relatively gentle species that’s generally harmless to humans. “There are lots of them around here. In the waters around Batu Batu’s restaurant, you can find seven to eight of them circling during low tide,” he adds.

To support the hatchery, guests can adopt a turtle nest for MYR300 (about US$72) or more; in turn, TIC provides sponsors with hatching statistics, photos of the baby turtles and recognition at the sponsored nests.

At Batu Batu, you can relax to the rhythm of waves crashing onto the rocks by the seaside pool, or knead your woes away with a traditional oil massage at the resort spa.

For some outdoor action, kayak into the big blue, or hike through the island’s jungle where multiple lookout points offer panoramic views of the surrounding islands.

Or consider the impact of human action on our planet; check with the TIC team on whether you can participate in its beach clean-ups.

In 2018 and 2019, they collected close to 23,080 kg of mixed marine debris (which included 44,140 individual plastic bottles) and removed 10.56 tonnes of “ghost gear” such as lost fishing nets, through their beach and underwater clean-ups.

At the end of each week, all recyclable items collected are sent to Clean & Happy Recycling in Mersing — the closest town 20 minutes away by boat.

Aside from leading regular beach clean-ups, Batu Batu has also ventured into Mersing schools, conducting environmental awareness programmes.

“Tourism industries are where things are really beautiful. And if that beauty is destroyed, that destroys the tourism industry,” says Cher. “So if we really want to push change and develop sustainable tourism, we can’t sit here and preach. We have to try and win Mersing locals.”

Recalls Zam: “On my first day with TIC, [Cher] wanted me to come up with a proposal for the school programme right away! After months of discussion, we managed to come up with the name ‘PEDAS’, short for Pasukan Pendidik Ekologi Dan Alam Sekitar.

“In Malay, this acronym has a double meaning: It has an environmental theme, but also means ‘hot and spicy’! Which is rather catchy and funny, especially for school kids.”

A multi-stakeholder environmental education programme for Mersing’s schools, PEDAS’ partners include Reef Check Malaysia, Trash Hero Mersing, Johor Marine Park Department as well as Mersing’s District Council, District Office and Education Office.

The partners worked together to create the programme, which comprises five modules on marine ecosystems, coral reefs, sea turtles, marine mammals and marine debris, and visit schools together to conduct outreach.

“The students don’t know we have sea snakes, groupers, dolphins and sometimes dugongs here as well! They say, ‘Really? How come we’ve never seen them? How can we see them?’ That’s when we’re able to tell the children: ‘If you want to see them, you have to conserve them’,” says Zam.

Batu Batu began as a private island destination, but it has grown beyond its shores and into the community at large.

Its latest venture is KakakTua, a guesthouse, cafe and community space in the heart of Mersing, converted from a 1950s shophouse.

“We get 500,000 tourists in the Johor islands and Tioman every year, but Mersing hardly benefits from that. People literally get out of their car or taxi, they look for their boat, and they go,” says Cher.

Through community arts, crafts and cultural programmes, Cher hopes that KakakTua will help to grow local appreciation for the town’s unique heritage, and encourage them to develop initiatives to help Mersing’s tourism scene thrive.

“We believe that increasingly, tourists are looking for authenticity. And what’s authenticity? It’s looking into the soul of a place. Looking into the lives and listening to the stories of its people. By starting KakakTua we hope to initiate the development of authentic tourism products and co-create an ecosystem of regenerative tourism, which will be driven by Mersing’s communities.”

Be a guest at Batu Batu Resort — a stay supports important conservation work on the island and beyond. In 2019, about 10 per cent of Batu Batu’s profits went towards funding Tengah Island Conservation, which has a team of five full-time marine biologists and environmental scientists stationed on the island.

Alternatively, adopt a turtle nest, or make a donation to Tengah Island Conservation.

Batu Batu also practices and champions sustainable tourism practices:

Low-density development (just 22 villas) to limit human population on the island

No disposable toiletries/single-use items (shower gel, shampoo, conditioner are in large refillable bottles; no toothbrush, shower cap, cotton buds)

No single-use plastics (no plastic bottles; glass bottles and glasses provided)

Solar panels that will fulfil 30 per cent of the resort’s energy needs

Water treatment systems to treat sewage (so no dirty water is discharged into the sea)

Weekly recycling – all recyclable items are sent by boat to Mersing’s Clean & Happy Recycling

An organic garden that supports guest and staff kitchens

Cher Chua-Lassalvy is co-founder of Batu Batu, a private island resort that funds a conservation non-profit to research and protect marine biodiversity.

“Islands are like a microcosm of the world. So if I chuck rubbish or sewage into the sea around Tengah Island, we’ll see the impact really quickly. We’ll see the coral reefs dying. And if that happens, we’ll see the fish population decrease. We might stop seeing turtles coming to nest.

It dawned on us that people in towns and cities need to care about what’s out here, or the environment is going to get destroyed really fast. That’s when we started to think about how we could reach out to Mersing, the nearest town to us.

So my team and I came up with the idea of opening KakakTua, a guesthouse and community space in Mersing town, where we can run programmes to upskill locals, and so on, so they can benefit economically from the tourism that comes through Mersing.

Currently, 500,000 tourists visit the Johor islands and Tioman every year, but Mersing hardly benefits from that. Tourists literally get out of their car or taxi at the jetty, look for their boat, and off they go. And that’s a shame because the locals don’t get why the tourists come here – and they don’t see the fragility of the marine environment.

Practically speaking, KakakTua is also a benefit to Batu Batu, as our guests who arrive later in the day can choose to stay a night at KakakTua – and we’ll give them a little guide on where to go around Mersing town. Where the nice seafood restaurants are, where they can eat nice ikan bakar, perhaps even visit a nearby kampung.

And then the next morning before setting off to Batu Batu, they can have roti canai at Rasa Sayang or head to Sri Mersing kopitiam for homemade custard tarts, boiled eggs and coffee.

The more we spend time in Mersing and hear stories from locals like Mr Lim Poo Ker, the more meaningful the town becomes. For instance, I never noticed the old Chinese medicinal shop until he pointed it out. And there’s the goldsmith – which has been around since 1935!

We believe that increasingly, tourists are looking for authenticity. And what’s authenticity? It’s looking into the soul of a place. Looking into the lives and listening to the stories of its people.

So we hope to create a really nice ecosystem of people who actually want to protect Mersing’s heritage, and then start working together to protect it.”

Meet Zam of Batu Batu and Poo Ker of Clean & Happy Recycling

Read more about Batu Batu

Zam is an Outreach Coordinator at Tengah Island Conservation, a non-profit that researches and protects marine biodiversity funded by Batu Batu resort.

"I got my degree in Marine Science from University Malaysia Sabah. My passion for the sea came up during my foundation year at the university, when I was exposed to other career options aside from being a doctor! In my family, it was either you become a doctor, lawyer or engineer. But one of the lecturers opened my eyes to the opportunity to explore the marine world.

“One of the main problems around the Johor Marine Park is pollution due to plastics and ‘ghost nets’ (abandoned fishing nets). In 2019, just from the six islands where we do regular beach and underwater clean ups – Tengah, Besar, Hujong, Mensirip, Harimau and Gua – we’ve collected more than 11 tonnes of ghost nets, plastics and other debris. On Harimau alone, we collected two tonnes of ghost nets and abandoned fishing gear such as fish cages.

Can you imagine what happens if ghost gear isn’t picked up? I’ve personally seen scars on dead fish that are trapped inside abandoned cages. These cages are often made from chicken coop wire, so it can be sharp as well. And when fish are trapped in there for an extended period of time, they get stressed and start to scratch themselves against the cages.

On the bright side, what has been encouraging to see is the impact from PEDAS – our multi-stakeholder environmental education programme in Mersing’s schools.

Every two months, PEDAS partners take turns to go into schools to teach students five modules on marine ecosystems, coral reefs, sea turtles, marine mammals and marine debris. The kids have no idea how beautiful Johor Marine Park actually is!

In 2019, PEDAS reached around 500 students across three primary schools and two secondary schools. And we’ve started to see a change in attitudes. For example, at SMK Sri Mersing, they’re limiting the usage of plastics in the school. Students have started bringing their own water bottles and even food containers to buy food from the canteen. And this change isn’t being enforced by us, but by the school. It’s great to see the school realise these everyday changes have an impact on the environment.”

Meet Cher of Batu Batu, and Poo Ker of Clean & Happy Recycling

Find out more about Batu Batu

People doing good. Causes you can support. Subscribe for a weekly dose of inspiration.

Our Better World is the digital storytelling initiative of the Singapore International Foundation, which brings world communities together to do good.

Our Better World is the digital storytelling initiative of the Singapore International Foundation, which brings world communities together to do good.