Coffee, crater lakes — and the Lio way

Visit RMC Detusoko

Kelimutu is more than its famed crater lakes. Travel with RMC Detusoko and immerse yourself in the agricultural heritage of Flores’ Ende-Lio highlands, and its role in the founding of modern Indonesia.

MEET THE LIO PEOPLE

“The house is our mother. The mother has an esteemed position in our society,” says Aloysius Leta, a Wologai village elder, as he shows me into his traditional house in the village.

Known for its traditional houses with its distinctive thatched roofs, Wologai is one of the oldest Lio villages in Flores’s Ende-Lio highlands. Lio people profess to be descendants of one mother and one father from Mount Lepembusu, and the Lio traditional house reflects this “one mother” narrative.

Though predominantly Catholic, much of the Lio people’s daily life are still governed by their pre-Christian customs. As such, rituals such as agricultural ceremonies, prayer offerings to ancestors, and the annual Kelimutu festival honouring ancestors are commonplace.

An invitation to enter a traditional Lio house is a sacred and intimate gesture. The veranda through which guests enter symbolises the mother’s open hands and heart, says Aloysius.

Next to the entrance is a carving of a pair of female breasts, which guests are to touch with quiet reverence upon entering. The interior of the house symbolises the mother’s womb and a communion of brotherhood.

Striking as they are, all of Wologai’s houses are reproductions of the originals — fires are a recurrent plague, and Aloysius has witnessed four Wologai fires in his lifetime. The last one in 2012 took just 15 minutes to consume every single house in the village.

“Despite these trials, we don’t run away. We remain here to guard our mother,” says Aloysius.

And it is this sense of pride and guardianship over Lio heritage that Ferdinandus “Nando” Watu seeks to preserve and share with the world through RMC Detusoko.

ONE HEARTH, ONE MOTHER, ONE HOUSE

RMC Detusoko is a collective founded by Nando and a group of young Lio farmers from Detusoko district, which encompasses Wologai, as well as Detusoko Barat, Nando’s village.

Deeply grounded in their agricultural and spiritual traditions but aware of the need to tap economic opportunities beyond their home, RMC develops the capacity of local farmers for ventures into hospitality and artisan food production — fields beyond traditional farming, but within reach with the proper support.

In 2017, RMC founded Decotourism to manage RMC’s travel venture, taking advantage of the Lio villages’ proximity to one of Ende regency’s prime attractions: Mount Kelimutu and its famed tri-coloured lakes.

With Decotourism, you take in not only the wonder of the lakes, but also the diverse ways in which young Lio farmers interpret the spirit of Kelimutu.

Revered as the final resting place of Lio ancestors, Kelimutu was once restricted as a Lio prayer ground. In the 1930s, an exiled Sukarno (also spelled Soekarno) — who later became Indonesia’s first president — used to trek here to meditate. During his exile in Ende, Sukarno became influenced by Lio philosophy, which he tapped for his vision of a decolonised, multicultural republic.

“Our Lio identity can be summed up as lika, iné and oné: we are a people of one hearth, one mother and one house.”

Nando Watu, founder, RMC Detusoko

Our visit began at 4am, where, dressed in layers to ward off the chill, we set off on a drive in pitch dark for our Kelimutu sunrise walk. Halfway through, our car pulls over. Nando steps out with a cigarette and a preparation of areca nuts, betel peppers and ground limestone.

But this isn’t a cigarette break; we are at Kelimutu’s ritual gate, the Konde Ratu prayer rock. Presenting these offerings to his ancestors, Nando prays for our travels.

We then commenced the 30-minute light trek. Initially, I needed a headlamp to light my way. But soon, the first glimmers of daylight came piercing through the velvety violet skies, and the cold receded.

A Kelimutu sunrise is like watching nature’s orchestra — the wind conducts blankets of clouds in waves over the three lakes as the landscapes change colours, accompanied by a choir of rare garugiwa, the Bahasa Indonesia name for the bare-throated whistler.

The three lakes in Kelimutu’s craters are known for changing colours, possibly due to the chemical reactions between the minerals and volcanic gases. Locals believe changes in the lakes’ colours present certain omens, and that each lake is designated different spirits: the spirits of those who died young, those who died in old age, or those who used supernatural powers for evil when they were living.

These spiritual landscapes are the foundation of RMC’s work: drawing on the philosophies of Lio identity to develop opportunities relevant to today’s world.

A FUTURE AT STAKE

A former journalist, Nando had long been interested in developing the Ende highlands’ tourism potential. In 2014, he was awarded a scholarship to an ecotourism management study programme in the United States.

On his return home, he worked as a facilitator for community-based tourism and solid waste management projects in the Ende highlands. One of his projects was Waturaka village, which won a national award in 2017 for Best Rural Ecotourism in Indonesia.

Drawing on his lessons with Waturaka, Nando, who was recently elected village head of Detusoko Barat, hopes that RMC can persuade young locals to stay home instead of venturing abroad for jobs.

“Indonesia loses up to a million farmers each year because young adults shun the farm. Although it’s good that farmers’ kids are getting higher education, it is a problem when parents establish the mindset that farmers are a low social class not worth joining.” says Nando, who is in his 30s.

“Our farmers are now typically over 45 years old, and we wonder why we’re suffering labour shortages for harvesting our otherwise profitable cloves, cocoa, rice and coffee,” he adds.

RMC seeks to show young Ende-Lio highlanders the kind of future in store for them if they choose home.

Its achievements include a partnership with Javara, a premium indigenous artisanal food brand, and participation in the British Council’s Active Citizens programme, the annual Kelimutu Festival, and exhibitions in Thailand and South Korea.

It also provides scholarship opportunities ranging from half-year tourism programmes in Bali to bachelor degrees in agriculture.

Decotourism now sees steady bookings from around the world, as well as support from Wonderful Indonesia — the state tourism authority — for participating homestays.

During our trip, we visit Waturaka, where we meet one of its ecotourism pioneers, Blasius “Sius” Leta Oja, a farmer who owns Sius Homestay. The homestay is also the rehearsal space for Nuwa Nai, a music group that handcrafts Lio instruments similar to the mandolin, flute, and violin.

Nuwa Nai performs a Lio song about the spirits of Kelimutu and for the community to stay united in a changing world, moving our driver Igen to tears.

“We are proud to preserve our culture,” says Sius. He adds that economic opportunities from performances and tour packages at Nuwa Nai keep young Waturakans home, who otherwise would migrate to work in East Malaysia’s oil palm fields.

FROM FARM TO TABLE

Back in Detusoko, we go on a scenic half-day hike, consisting of an uphill walk through vast swathes of rice fields, panoramic views at farmers’ resting huts, and moments of peaceful silence at megalithic gravesites.

The destination is Nando’s coffee plantation, where Igen and a crew of interning university students have prepared a picnic over the bonfire. After lunch, we picked ripe robusta coffee cherries and drive back with Igen.

At Nando’s house, RMC members are busy sorting the harvest with members of Universitas Flores’ agricultural faculty. Sorting is a social event filled with chatter and hot drinks, during which I learn about the different grades of robusta coffee.

Later, we taste the coffee in RMC’s Lepa Lio café, a hangout spot for Decotourism guests decorated with classic Flores details such as bamboo furnishings and palm leaf weavings.

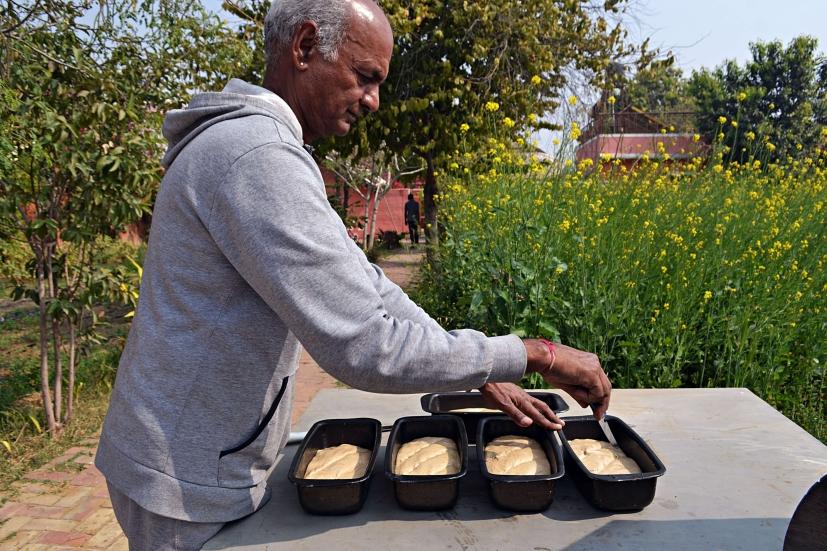

Lepa Lio is also the production hub for RMC’s house brand, From the Fernandos’ Family Farm. Products — developed in collaboration with Javara’s food artisan academy — include peanut butter, marmalade, koro degalai (Lio for chilli-tomato relish), coffee, black rice, and sorghum.

Imelda Ndimbu, one of Lepa Lio’s employees, demonstrates how to create peanut butter — roasting the peanuts to perfection, weighing the right amounts of other locally-sourced ingredients such as sea salt and virgin coconut oil, and sterilising the jars in a hot bath.

Naturally, I bought all the jars of peanut butter we made, and then some.

Nando also makes it a point to bring his guests to shop at other social enterprises in the Ende-Lio highlands, including the Wologai coffee shop and the Sokoria farmers’ collective.

This rings true to the Lio philosophy of equal opportunity and interdependency in business; good fortune is shared with the folks of one hearth.

We end our trip with a tour of Ende city, visiting the historic sites where Sukarno drew influence from Catholic priests and Ende-Lio communities for the nation he would later found in 1945 — Indonesia.

Months later, I am still processing and learning from the memories of this eclectic trip. What lingers is the sincerity of the relationships that make the Lio identity, how these relationships promise a bright future for its young farmers, and how, not too long ago, they served as inspiration for the nation I call home.

“Come as a guest, leave as family.”

Nando Watu, founder, RMC Detusoko

Travelling with Decotourism supports sustainable livelihoods for young Lio highlanders who choose farming at home over careers in cities. Retaining well-educated, productive youth in the village promotes economic growth, cultural resilience and indigenous stewardship in the Ende-Lio highlands.

By including in your itinerary visits to cultural heritage sites such as Wologai, and activities such as the Nuwa Nai performance, you help keep alive the sacred spaces where Lio highlanders share their cultural memories.

Proceeds from Decotourism also help RMC invest in its members through higher education and career opportunities, in fields previously beyond locals’ reach, such as hospitality, artisanal food production, and enterprise.

RMC members are selected through an interview process and assigned to suitable business units. It retains 10 per cent of the rates paid for these jobs, to cover operational costs.