An ikat collective weaves its way through knotty times

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, is there a more iconic accessory than the ubiquitous face mask?

On the website of Noesa, a Jakarta-based favourite among the sustainable style-conscious set, face masks made with beautiful ikat fabric are front and centre, as part of their Corona Survival Kit collection.

But these colourful textiles are more than just a symbol of these unusual times: they are part of the tapestry of empowerment and cultural preservation woven by Watubo, a collective from Sikka regency in Flores, Indonesia.

A traveller could once participate in a weaving workshop by Watubo in their village of Watublapi, which provided the weavers a vital source of income while safeguarding their craft. But the pandemic has ground these efforts to a halt.

With a little help from customers looking for something special, Watubo weavers hope to restore not only some of their income, but also their platform for sustaining and reinventing their ancestral craft.

Meet Rosvita

“Ikat represents a woman’s worth,” says Rosvita Sensiana, an ikat artist with more than 20 years of experience. “Our ancestors didn’t have clothing stores, [so] to clothe her children and husband, a Sikkanese woman toils with her body to weave ikat.”

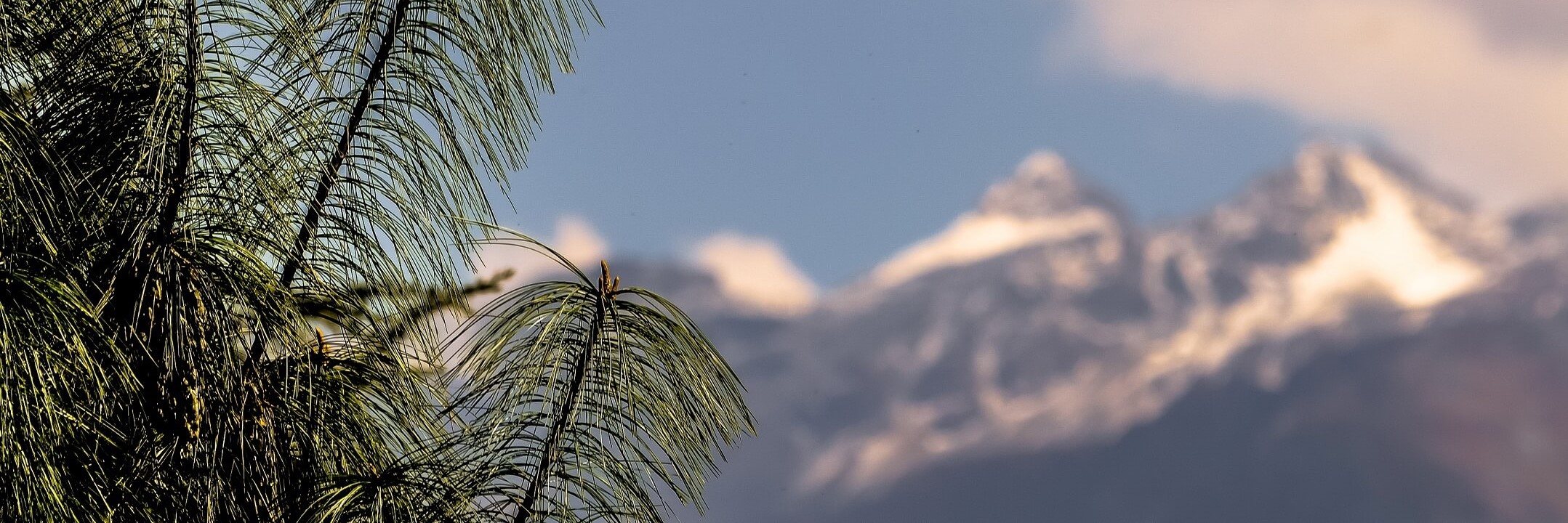

Ikat means “to bind” or “knot” in Indonesian languages, and Sikka regency is one of the most reputable producers of fine ikat in Indonesia, with centuries’ worth of vegetable dye traditions. Born into a family of Sikkanese master weavers, 36 year-old Rosvita is the founder of Watubo.

Before the pandemic, Watubo made most of its income from taking part in national and international exhibitions, as well as hosting travellers to its ikat workshop, where participants could learn the craft while enjoying the sights, sounds and stories of Sikka.

All this changed when the pandemic struck in 2020, but Rosvita is confident that Watubo will find a way to prosper again. “Watubo means ‘breathing rock’ or ‘living rock.’ It represents our belief that no matter how hard a place is, we will certainly survive,” she says.

Introduction to ikat

I met Rosvita in 2019 before the pandemic when I took part in Watubo’s ikat workshop, a collaboration between Watubo and Noesa.

“An ikat workshop would attract visitors, which would help promote Watubo and increase weavers’ earnings,” said Rosvita then, adding that participants’ respect for ikat is also the goal.

Noesa provided the funds to build a homestay for guests and handled the online bookings. The workshops also included a tour of Sikka led by Rosvita.

But these workshops are on hiatus indefinitely, and for now, avid travellers can only experience the rich history of Watubo’s ikat through the wares sold on Noesa.

Ikat is popular worldwide, but my interest in it is personal. My maternal great-grandmother, originally from Roti island near Timor, was a weaver who clothed her family in elegant, handwoven ikat bearing intricate motifs identifying their surnames.

I never met her, but I still hold a sarong that she wove for my grandmother in the 1950s — an heirloom no one in my diasporic extended family can replicate.Since my family had lost this cultural knowledge, I had come to Sikka to learn from another weaving culture. But even in Sikka, where ikat is considered to be thriving and current, perpetuating the culture has neither been easy nor straightforward.

Many Watubo weavers are alumni of Bliran Sina, an older collective founded by Rosvita’s father, which focuses on the most traditional forms of Sikkanese ikat, and subjects weavers to a myriad of protocols and taboos.

Although Rosvita supports preserving tradition, she believes that innovation upgrades weaver’s livelihoods because it opens up markets otherwise impenetrable by traditional ikat.

In 2014, she started Watubo with Noesa’s support. The collective allows younger weavers to explore creative innovations such as novel colours and contemporary motifs. These updated iterations of ikat can be applied to products such as camera straps and wallets. In contrast, traditional ikat bear sacred images and cannot be used in the same way.

Watubo became Noesa’s first artisan partner, connecting its weavers to Noesa’s urban consumers, and becoming a success story of a woman-led rural creative enterprise.

Threads of a rich history

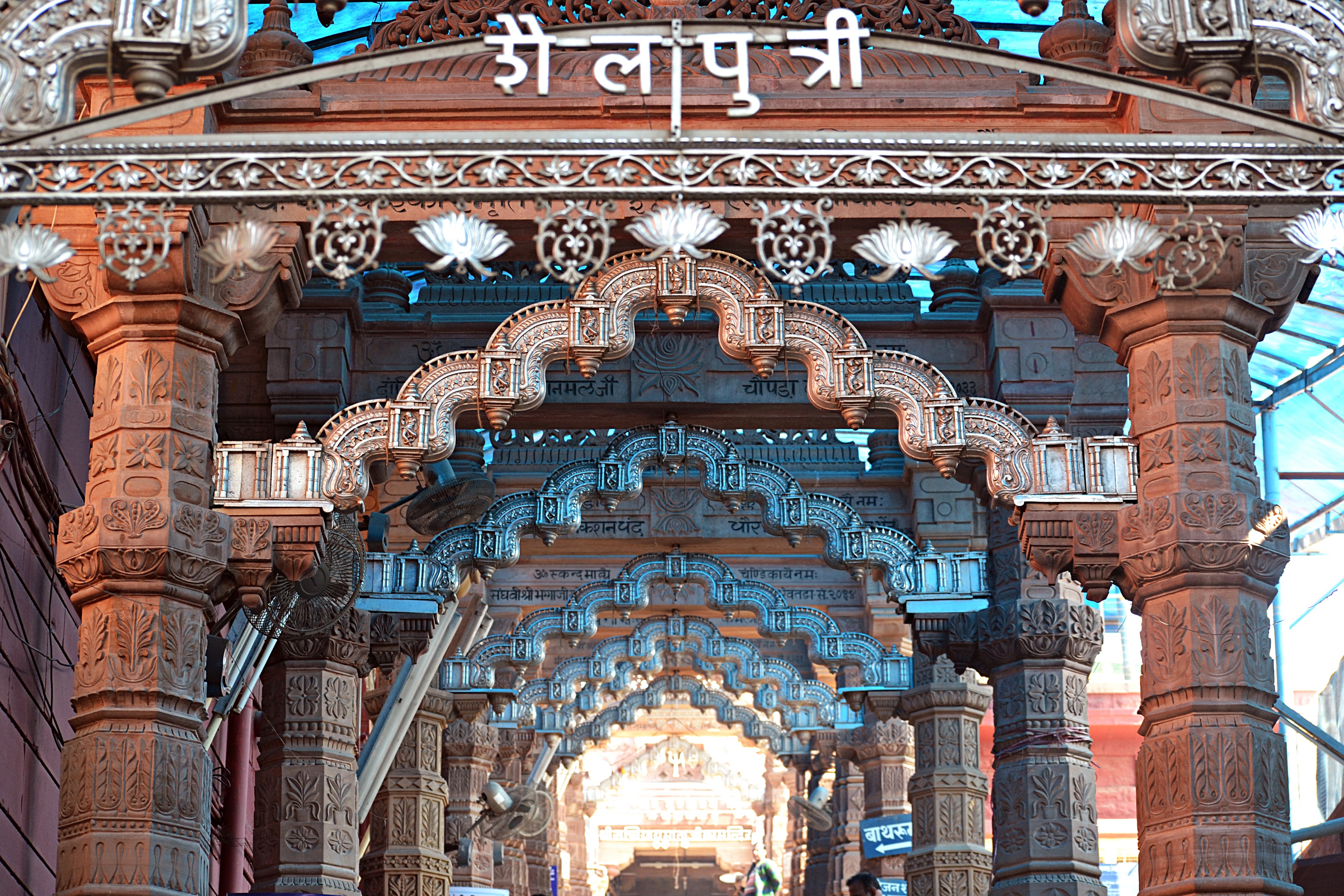

A former Roman Catholic kingdom that ruled parts of central Flores from 1607 to 1954, Sikka may not have royal heritage sites matching Java and Sumatra’s grand royal palaces , but it can hold up ikat as one of royal Sikka’s biggest remaining testaments.

It is a discipline that is not only arduous, but also easily rendered meaningless when divorced from a practicing community and their culture, which provide ecological and historic context to the craft.

Watubo’s workshop, named Orinila (“House of Indigo” in Sikkanese), aimed to preserve this connection. Guests are welcomed with a ceremony involving dance, music, offerings to Watublapi ancestors, a formal introduction to express the guest’s intention for visiting, chewing betelnut, and a Holy Communion-like ritual of eating chicken and rice.

Next, the weavers and I discussed our lesson plan. I produced a grid paper drawing of my grandfather’s Johannes clan motif, to be woven into a scarf.

No newbie finishes a scarf in three days, so the workshop involves a dozen weavers demonstrating works-in-progress at different stages, and allocating time for a guest to practice each stage. Watubo then completes the scarf and ships it to the guest later.

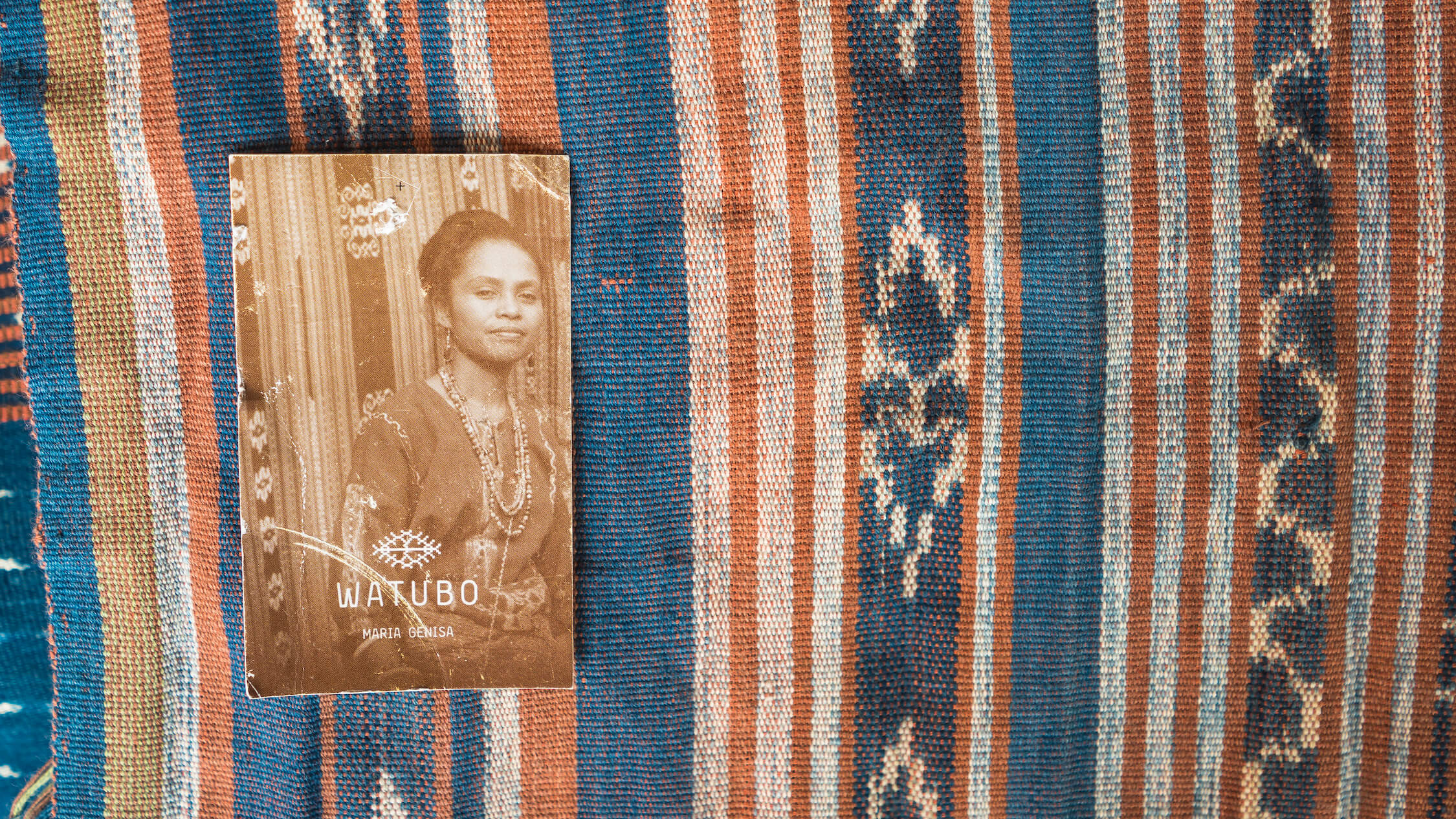

On day one, I recognised my instructor Maria Genisa, having previously bought her work. Though I had only seen her photograph and name on a Watubo label, it felt like I was meeting an old friend.

Genisa and I spun hanks of cotton thread into balls, and wrapped them around a warp frame. I learned that Genisa’s husband Yohanes Mulyadi is a Watubo colourist. Yohanes also grows cloves, but he and Genisa found weaving a better source of income.

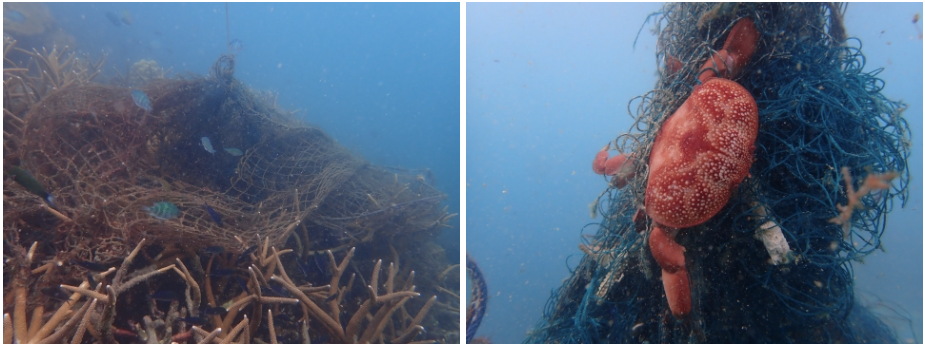

A weaver from Watubo demonstrates resist-binding, a process of binding the yarn to create the desired motif. Photo by Andra Fembriarto

Meanwhile, on another frame, Virgensia Nurak taught me how to translate my paper study into the right proportions for resist binding — binding yarn with a tight wrapping applied in the desired pattern.

It was hard. The shape of my resist kept skewing as though it was having spasms, and I needed Virgensia to pull them back into the motif’s normal shape. We spent three laughter-filled hours together, where I only managed to bind 8cm of resist over 5cm of warp.

The next morning, Virgensia had finished binding the resist for my scarf, and it was ready for dyeing.

Rosvita explains Watubo’s commitment to vegetable dye: “Firstly, it preserves our ancestors’ cultural heritage. Secondly, it is safe for women, children, and the environment. Thirdly, it encourages us to regrow and conserve culturally important plants, and harvest them sustainably.”

Vegetable dyeing also allows weavers to experiment and be surprised by the results. “Soaking threads in experimental vegetable dye recipes makes my heart pound,” says Rosvita.

Morinda red is the trickiest colour. Threads need prepping overnight in an oily candlenut pre-mordant before colouring red. I was already breaking a sweat as I pounded the pre-mordant using a tall wooden pestle and a deep stone mortar. After that, I still had tough morinda roots to cut up and pound into a pasty dye.

When I was done, I felt like I had finished rowing cardio at the gym, but with an awestruck feeling as I watched milky white threads turn crimson with a touch of berry.

I started day three watching the vibrant threads we dyed dry in the sun. Opening the resist and rearranging the resist-dyed threads over the warp frame to form the intended motif is painstaking work.

When I finally sat at the loom, I moved the weft to and fro through the warps and watched them transform into fabric. In two hours, I weave a mere 4cm.

My emotions brimmed over the goodbye dinner. I’d always thought my urban lifestyle and career made it impossible for me to learn ikat, but Watubo made my first step in this long journey possible, immersing me in a labour-intensive process that revived our ancestors’ creative spirits.

A pandemic pause

Rosvita has been vocal about how Watubo has financially changed her life.

“I had nothing before Watubo,” Rosvita had told me during my visit. “[After Watubo] I’ve bought a house and a motorbike. I am reaching prosperity. I have everything I need.”

Other weavers have used money earned from Watubo to send their children to university, or to develop farms from which they can earn even more.

Because of this, Watubo had become a full-time livelihood for many weavers and their families, who would otherwise earn less as farmers, labourers or working for the government.

Now it’s a different story. “During the pandemic our finances haven’t been as great,” says Rosvita. “Earnings from ikat have been difficult to rely on, so weavers currently rely more on agriculture.”

The few sales that happened during the pandemic were mainly from Noesa and “very few other visitors,” mostly Flores locals. For now, Watubo has to sustain the resources to resume full production in future. “We hope this pandemic ends soon, to resume our activities and join exhibitions again,” says Rosvita.

Until then, a simple ikat mask remains to tell the rich history of this inspiring collective.

By shopping Watubo products, you support the development of Sikkanese ikat as a sustainable livelihood for Watublapi residents. To date, Watubo has worked with 25 weavers, most of whom are women under the age of 50, as well as a few men.

Supporting demand for vegetable-dyed ikat also encourages weavers to stick with dyeing processes that are safe for people and the environment, and to conserve culturally important plants such as morinda and indigo.

Supporting ikat as a sustainable profession in Watublapi would encourage their young people to stay in the village and contribute to the community. A strong ikat business also encourages other collaborations, such as working with Watublapi graduates who have left the village but whose business skills and connections to the outside world can benefit weavers.

You can find Watubo's original creations on Noesa's website. Look out also for ikat items made with fabrics from Watublapi by Noesa.

Noesa can be contacted for further enquiries about Watubo via WhatsApp at +62 81315556670.

Meet Rosvita of Watubo

Help Watubo stay on course during the pandemic

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways you can support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

![Keaw getting ready to showcase the culinary gems of the Akha tribe [left]. She hopes that interest in northern Thailand cuisine creates more interest in the country’s indigenous cultures. Photo from Local Alike](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Webp.net-compress-image_0.jpg)