Celebrate! A Mollo gathering of arts and food

Support Lakoat.Kujawas and Decotourism

In Timor’s Mollo highlands, life-giving waters, rocks and trees — and their devoted guardian clans — flourish. Lakoat.Kujawas rekindles intimate knowledge of this land through creative arts and food.

MEET DICKY AND LAKOAT.KUJAWAS

“We, Orang Mollo, are a people of gatherings,” says Christianto “Dicky” Senda. “We called our gatherings elaf. It’s a moment where people meet and hear the spoken word, tales, and genealogies.”

Elaf came to life before my eyes, writ large in the form of a celebration marking Indonesia’s Independence Day, where, with the state’s blessing, North Mollo residents dressed up and performed traditional songs and dances at a talent show in Kapan Square, the district’s centre.

But nearby, another celebration was taking place: an exhibition of photography by 11- to 15-year-olds; and the launch of a book of poems by To The Lighthouse, a writing club at Kapan’s St Yoseph Freinademetz Catholic Middle School. Under a flowering tree by the bonfire, a youth choir harmonised.

“These teenagers are making contributions to this village,” observes Father Jeremias “Romo Jimmy” Kewohon, principal of St Yoseph, with pride. He credits this creative revival among his students to Lakoat.Kujawas, a Timorese literacy centre and social enterprise founded by Dicky.

Now, Lakoat.Kujawas also welcomes travellers to explore this corner of South Central Timor, in Indonesia’s East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) province.

CELEBRATING TRADITIONS

A former student guidance counsellor in Yogyakarta and Kupang, Dicky started writing stories inspired by Timorese fairy tales from his childhood. The need to conduct research for his books, and care for his ailing father compelled Dicky to move home to North Mollo’s Taiftob village in 2016.

Upon his return, Dicky saw that Mollo hadn’t changed much since his childhood. Children still had little access to educational playtime. Meanwhile, knowledge of Timorese oral tradition, indigenous spirituality, guardianship of natural resources, Timorese cuisine, and tenun (handwoven textiles) was dwindling.

“Lately, festivities, rituals, and harvest thanksgivings are not happening anymore,” says Dicky. “Without elaf, we’re deprived of spaces for telling our stories.”

So Dicky opened a library — a little elaf space for North Mollo children. It has since hosted English classes, a writing club, dance workshops, photography projects, music rehearsals, and a residency for visiting creative professionals.

Eventually, adults who miss their elaf joined in too. Working with local schools and creative youth communities, Lakoat.Kujawas now brings back the arts into everyday life for Orang Mollo (Bahasa Indonesia for the Mollo people), while recording them for future generations.

CELEBRATING HERITAGE

“We are our world. Soil cover our land like our skin.

Water flows through the land like our blood

The stones holding the land together are our bones

The forest moving with the wind is our hair.

We are our world.”A Mollo philosophy

Dubbed “the heart of Timor,” North Mollo’s Mount Mutis is the source of four major Timorese rivers, with diverse ecosystems like bonsai forests, eucalyptus woodlands and horse-grazed meadows.

Travel experiences to Mollo were not on Dicky’s mind when he started Lakoat.Kujawas. The venture into tourism — focusing on heritage trails, culinary products, and tenun textiles — happened in response to outsiders’ appreciation for his community’s creative revival.

Hence, once a month, from January to August, Lakoat.Kujawas runs the M’nahat Fe’u Heritage Trail, which are guided trips introducing travellers to North Mollo’s natural landscapes, culture, and food.

M’nahat fe’u, which means “new food” in Dawan language, is a harvest elaf, and each trip varies according to the harvest of the season.

I was lucky enough to join the last trip of the year, which kicked off with a satisfying breakfast prepared by Lakoat.Kujawas members: black beans, steamed yams and coconut sweetened with palm sugar syrup, and pumpkin cake with marmalade. This was served with coffee (including a robusta blended with pumpkinseed), sweet fruity cascara tea made from coffee cherries husks, and loquat leaf tea.

Guiding this tour is Willy Oematan, who takes us to the Oematan wellsprings, introducing native plants and related rituals along the way. The Oematans are a revered Mollo clan traditionally designated as guardians of water sources, with their rituals being passed down through strict protocols.

From there, we hiked up Napjam Rock, where Lakoat.Kujawas members were cooking jagung bose maize porridge and broadbean stew over bonfires. Banana leaves became a picnic blanket set with palm leaf trays and claypots of Timorese dishes: smoked beef (seʼi), sweet-spicy chili-tomato relish (sambal lu’at), baked purple yams, cassava leaves in roasted pumpkinseed sauce, and a vegetable flower stir-fry.

Members of music collective Forum Soe Peduli lead a communal singalong as a prelude to lunch, and Dicky served consenting guests sopi lakoat: loquat-infused Timorese palm wine garnished with dried fruit.

Sopi, he shares, has cultural importance as a gesture of peace and camaraderie, and economic importance as a commodity that affords some Timorese families an education.

CELEBRATING LIVELIHOODS

Homegrown Mollo cuisine is a major component of the Lakoat.Kujawas brand. On the day before I joined the heritage trail, Marlinda Nau, a farmer and member of Lakoat.Kujawas, welcomes me with a bountiful display of fresh produce.

With a basket in hand, I follow the cooks to a pink flowering tree called gamal (Gliricidia sepium). At a distance, they could be mistaken for cherry blossoms.

Whack! Someone climbs the tree and chops off a branch. Petals fall like confetti. The flowers, I learn, were a seasonal Timorese vegetable before it fell out of favour to commercially-grown vegetables.

“Lakoat.Kujawas gives us the space to revive our traditional agricultural knowledge and innovate our homegrown food,” says Marlinda.

Her husband Willy adds that Taiftob produces more carrots than people can eat, so they sell some to middlemen at unfairly low prices. “Now, we make carrot noodles and carrot-based snacks. Our produce gets consumed, and we save money otherwise spent on children’s snacks,” says Willy.

“In Mollo, we joke that we sell our organic fruits and vegetables, and buy instant noodles and cookies instead. We used to think what we have at home isn’t important. But now we know better and we laugh because it’s ridiculous.”

Dicky Senda Co-founder, Lakoat.Kujawas

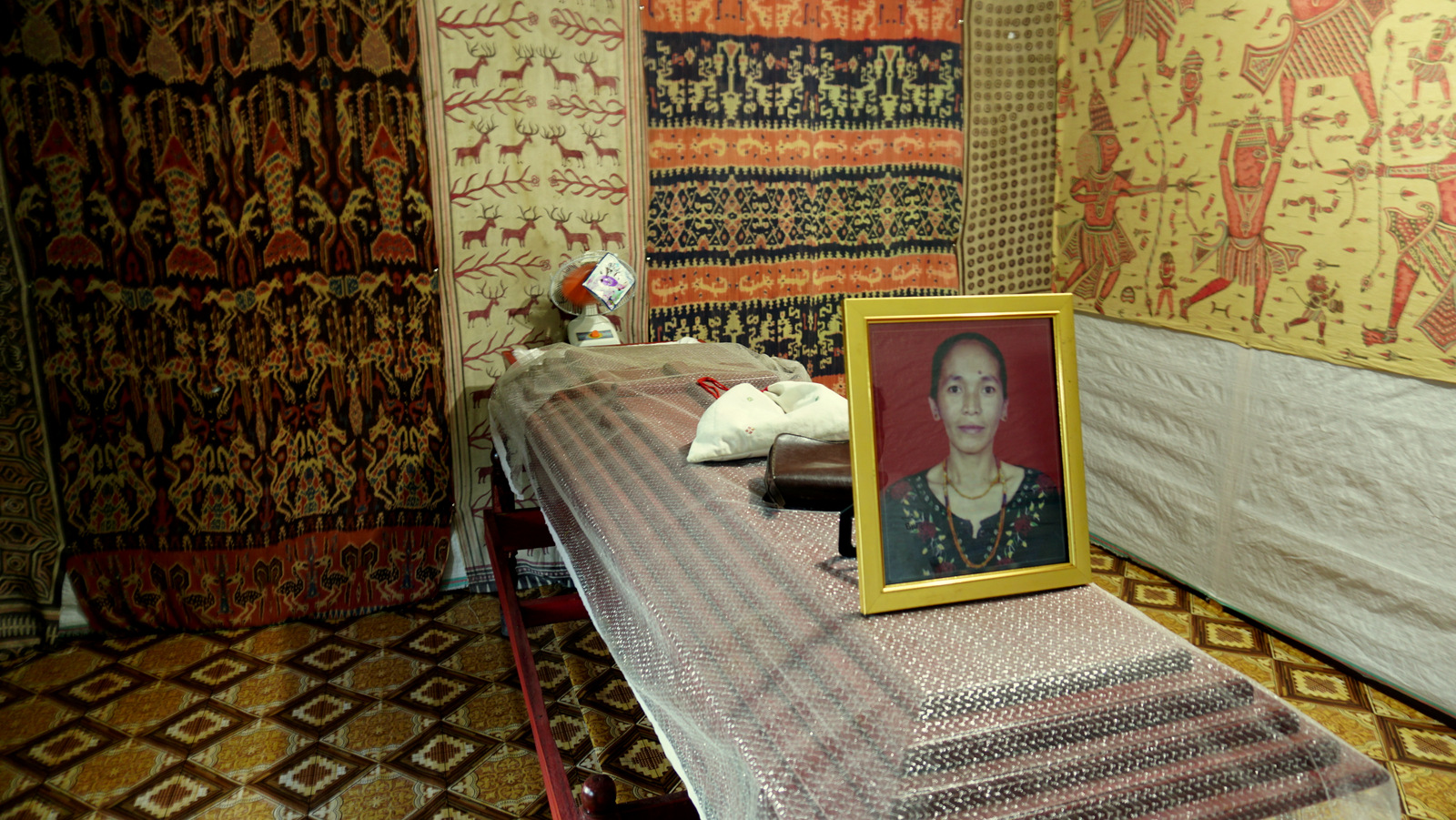

Tenun handwoven textiles is another aspect of Timorese culture Lakoat.Kujawas strives to preserve. This ancient craft involves the weaving of coloured threads into complex motifs, requiring imagination, meticulous hand-eye coordination, and patience.

In Nusa Tenggara society, tenun is a marker of a person’s social status, clan kinship and geographical origin. Today, tenun is also a profitable commodity marketed to travellers, fashionistas and collectors.

A prominent Lakoat.Kujawas weaver is Amelia Koi, who runs a family collective comprising her six daughters. “It’s hard to find young ones interested in tenun, so I teach mine,” says Amelia, who has them fully trained by age 11.

The girls stay in school until they graduate their final year of secondary school, around age 18 or 19. Although none attended university, her elder daughters are financially independent and experienced weavers.

Months earlier, I ordered a tenun backpack from a Yogyakarta-based brand that partners with Lakoat.Kujawas. The tenun is Amelia’s. “The work of my hand has returned ,” says Amelia, recognising the bag (pictured below). “My textiles travel further than I do. It feels that a piece of me travels along.”

My trip culminates in a march with thousands of North Mollo residents in Kapan’s Independence Eve Parade, many dressed in tenun as a statement of their local identity. But even as the most festive occasion of the year comes to an end, elaf is never over at Lakoat.Kujawas.

Says Dicky: “At Lakoat.Kujawas, we continue to grow and nurture… Our spirit is not project-based — it’s an elaf spirit that restores our cultural spaces with dignity.”

Lakoat.Kujawas runs seasonal single day tours, as well as creative residencies and Timorese food workshops. Bookings must be made in advance.

When you book a tour with Lakoat.Kujawas, or shop via their social media accounts, you help to fund local children’s educational programmes like the To The Lighthouse writing club, photography exhibitions, and performing arts productions — activities that are otherwise scarce in rural Timor.

Revenues from the Lakoat.Kujawas tours, artisan food production, and tenun partnerships fund the Lakoat.Kujawas cooperative, which is a source of income for adult members.

The cooperative is designing a collective savings programme, which they hope will someday help Lakoat.Kujawas families fund their children’s higher education, or support them through hard times.

Meet Dicky of Lakoat.Kujawas