The magic of a simpler life with rice

Visit Tigerland Rice Farm

Visit Tigerland Rice Farm

This farm in Chiang Rai will allow you to dig into the ins and outs of organic rice farming and experience the traditional way of life in the lush countryside. You also get the opportunity to support social impact programmes that benefit the community.

MEET KITT

Say hello to your intrepid host Kitt as he welcomes you with the warm hospitality of Northern Thailand. Kitt and his family are members of the Karen Sg’aw hill tribe community and they will guide and teach you all you need to know during your visit. Kitt’s mum, Mother Tomei, will keep your tummy happy and full. Kitt's father will not only work the fields with you, he may even serenade you with a folk song or two as you till the land together.

We use nature, we take many things from nature. So we should take care and give something back.

Kitt Tiger

Co-Founder, Tigerland Rice Farm

LOTS TO DO AND TONNES TO LEARN

Depending on which season you visit, you’ll learn how to either plant or harvest rice, from ploughing the rice paddy, planting rice seedlings, to getting the rice ready for consumption. Through this process, you will also learn about traditional and organic farming methods.

The serenity of Tigerland Rice Farm makes it an ideal place to practice yoga and do deep meditation. You can spend a few hours (or days) in silence in your private hideout. There are meditation huts and platforms out in the paddy field and in the bamboo forest.

There are also half-day or whole-day hill tribe cultural tours you can go on to explore the history and charm of the local communities.

When you stay at Tigerland Rice Farm, you help in the organic farming of rice, but there are other ways you can get involved in other community projects.

You can donate English story books with the Raise-a-Library project which helps set up more libraries in the village. This provides the hill tribe children with sufficient resources to improve their English.

You can be a sponsor in the Raise-a-Piggy project which provides a deserving family with a piglet to raise with care before they sell it off after a year. The money from the sale supports their children’s education.

You can donate a cow in the Raise-a-Moo-Moo-Cow project. A family raises the cow for about two years, during which they can use or sell the milk. Once the cow bears a calf, the cow will be returned to Tigerland Rice Farm to help another family. The money will support their children’s education.

Visit Mangalajodi Ecotourism Trust

After years of poaching, it didn’t look good for the birds in Mangalajodi. Then locals, realising the harm of their actions, reversed course. Let Mangalajodi Ecotourism Trust show you how they brought the birds back to this wetlands paradise — and travellers with them.

Meet Subhash

“When we didn’t know better, we’d kill and eat bird meat. On some occasions, we sold it to earn some money,” says Subhash Behera, a fisherman.

Two decades earlier, sentiments like Subhash’s were not unusual. Thanks to poaching, Mangalajodi’s bird population had dwindled to 5,000.

But today, Mangalajodi is a village transformed. Locals proudly show off the rich biodiversity of the area, and virtually all of them can rattle off the names of every bird species there in English, despite the language being foreign to them.

And every year, from October to March, the sleepy village is transformed by a flurry of activity.

Coming from as far as Siberia and Mongolia, migratory birds make Mangalajodi’s Chilika Lake — the second largest coastal lagoon in the world — their temporary haven. In turn, they draw flocks of passionate bird-watchers.

Hitting bottom, rising up

Mangalajodi, located in the state of Odisha, entered the spotlight in the 1990s when environmentalists began sounding the alarm over the plummeting native and migratory bird population numbers.

Then, fishermen like Subhash thought nothing of eating the various birds that had somehow gotten entangled in their nets. Others poached the birds, in the hopes of selling them for money.

A solution was desperately needed, and it wasn’t long before eco-tourism emerged as the prime candidate: perched on the edge of the serene Chilika Lake and its vast wetlands of swaying reeds, Mangalajodi is perfectly situated as a base for bird-lovers.

Thus, Mangalajodi Ecotourism Trust (MET) was established in 2010, uniting various ongoing efforts in the area into a community-managed and community-owned enterprise.

Guided by RBS Foundation India and its implementing partner Indian Grameen Services (IGS), MET succeeded by placing locals like Subhash at the front and centre of its efforts.

“The phenomenal knowledge of birdlife that the community had, was seen as a skill that an enterprise could use,” says Abhinav Sen from RBS Foundation, who helps manage the programme with the villagers.

Interested members of the fishing community have been trained as boatmen — including Subhash — while former poachers who once used their keen eyes and ears to hunt for the birds, now use them to complement their new roles as guides.

All bookings are made through the Trust and every member is paid their fee on a per diem basis, depending on the type of services delivered (e.g. Rs300 per boat ride).

The Trust runs also four earth-friendly cottages and one dormitory for large groups, and can accommodate up to 25 to 30 people at a time. Meals comprise items sourced from local fisherfolk and farmers.

Once down to just a few thousand, today, the bird population has rebounded to 300,000 at its peak.

A day in birder’s paradise

Armed with only oars and binoculars to help them spot as well as identify birds, the boatmen and guides are the eyes and ears of the guests, as they accompany them into the wetlands.

During bird-watching season, a typical day starts with an early morning boat ride where guests spend around two-and-a-half hours on a boat, quietly lapping through the waters to spot birds like glossy ibises, swamphens and godwits.

After breaking for lunch, one can relax for the day, before heading out in the evening to spot more prized birds, while being embraced in a glorious sunset.

“It feels good to have people come visit our village and stay here for a couple of days. It is a matter of pride and honour for us,” says Purna Chandra Behera, a guide.

One of the first to take to guiding, Purna Chandra was sent for training at the Indian Institute of Tourism and Travel Management in Bhubaneshwar, after he joined MET.

He now works as a guide during bird-watching season. “Today, my son, who is also a guide, has attended the same training programme and has been taught by my teacher,” he shares with pride.

Adds Subhash, now a boatman and conservationist: “It’s because of these birds that people from different parts of the country, and even the world, come to stay in our tiny village.

“In turn, this helps us earn a better income for five to six months of the year and take better care of our families.”

Looking at the future

Awarded “Innovation in Tourism Enterprise” at the United Nations World Tourism Organization Awards in Spain in 2018, MET is gaining traction.

Recognition has brought visibility and in turn an increase in not just the number of tourists, but also the number of stakeholders: governmental, corporate and individuals.

Purna Chandra, for example, has been seeing more boatmen ferrying travellers around, although they are not part of the trust.

But as they reap benefits from the tourism boom, MET is also asking itself: how much is too much?

“At an operational level, it means understanding how many boating trips can be offered per day without crowding Chilika and disturbing the birds in their habitat. It also means identifying ways in which we can accommodate tourists,” says Sanjib K Sarangi from IGS, who has been advising MET.

A village that rose to infamy as one of bird poachers has managed to rewrite its narrative, and demonstrate the power of collective action and reform.

Now it must decide how to chart its course, as it straddles the dilemma of economics and ecology.

Mangalajodi Ecotourism Trust is a community-owned initiative, which means every trip and stay with them, brings income to participating villagers.

This provides the community with greater income security and a vested interest in protecting the environment from further harm. Wildlife can flourish, while the standard of living for the community improves.

In January 2019, MET’s efforts won them the gold trophy for Best Wildlife Stay at the India Responsible Tourism Awards, organised by Outlook Traveller. MET was also recognised by the state government for its contribution to wildlife protection at the second National Chilika Bird Festival in 2019.

Visit Green Acres Orchard and Ecolodge

A treehouse getaway...on a durian farm? Fear not, you don’t have to love the stinky, divisive fruit to fall in love with the lush, eco-conscious surroundings of Green Acres Orchard and Ecolodge. This 16-acre orchard will show you why a sustainable life is a good life.

MEET THE CHONGS

With their galoshes, wide-brimmed farmer's hats, and glowing, tanned skin, Eric and Kim Chong are unlikely to be mistaken for corporate shills.

But the cushy office life was what this couple left behind, when they returned to their hometown of Penang in search of a more environmentally-conscious future for their son.

"We wanted [our son] Aldric to grow up in a place where he could run around in the great outdoors,” says Kim.

The answer came in the form of the stinky, spiky “king of fruits” — durians. A 16-acre orchard in Penang, to be exact, painstakingly cultivated by the Chongs into Green Acres Orchard and Ecolodge, a haven for durians to thrive as nature intended.

MORE THAN JUST A DURIAN FARM

Balik Pulau, literally “back of the island” in Bahasa Melayu, is Penang’s rural side, famed for cultivating different varieties of durian.

In an area chock-a-block with durian farms offering guided tours, durian parties and homestays, Green Acres has quietly emerged as a preferred destination for durian lovers looking for an escape from the crowd.

Eric and Kim keep visiting groups small because they want to keep things personal as they share their knowledge and experience in organic fruit farming, composting, building sustainable homes, and the heritage of Balik Pulau orchards.

Exploring the farm in their company, the Chongs' passion is palpable, and it’s not hard to see why. Many of their durian trees, inherited from the previous owner when they took over in 2009, are over 50 years old, and still productive.

For each tasting session, the Chongs pick durians on the morning of each group’s arrival to ensure they get the freshest fruits.

Don't worry if you're not a durian lover; there are plenty of other tropical fruits to sample — rambutans, cempedak, pineapples, and bananas, to name a few — as well as rare herbs and spices that many urbanites may have never seen.

Moreover, a stay at the farm’s eco-lodges is, despite the durian’s pungent reputation, a relief for the senses. Breezes roll in from the forest across gleaming wood floors and all is quiet, save for the soft thump of durians hitting the ground, ready for harvesting.

Guests can also relax in a pool that draws its water from a spring, and dine on the freshly-laid eggs of 70 chickens and ducks, which roam in a 10,000 sq ft coop, and supply, ahem, fertiliser for the trees.

"Here, the air is cleaned by the leaves. The water is filtered by the sand...We had a medical check-up recently and the doctor said, ‘Whatever you're doing, keep doing it!’"

Eric Chong

Co-founder, Green Acres

GREEN DREAMS

Staunch advocates of the slow food movement, Eric and Kim went on a three-year search before they found their hidden gem at 250m above sea level — ideal for growing durian trees, and accessible only via a steep, gravelly road punctuated by hairpin turns.

The farm already boasted a whopping 450-plus trees from 35 cultivars. More importantly, it had been chemical-free for three generations.

In the Chongs, they found the perfect torchbearers to carry on their all-natural legacy. No gentlemen farmers, the couple threw themselves into nursing the land back to health — the previous owners, then in their 80s, had been unable to keep the farm as productive as it could have been.

"In the early days, we had to put one bag of organic fertiliser next to each tree. Imagine doing this for 500 trees,” says Eric.

On any given day, there were fruits to be wrapped, heavy equipment to be carried, trees and animals to feed. Slowly but surely, the Chongs began to notice changes. "Our caretaker, who is from the original owner's family, told us the trees haven't been this healthy for years. During one bumper year, we harvested over 500 durians a day!" Kim shares elatedly.

A CUT ABOVE THE REST

Anchored to the forest floor by an 80-year-old durian tree, the Musang Loft Treehouse is one of the Chongs’ most striking additions to the property.

For one, there are no walls between your bed and the trees around you — just wooden railings and bamboo screens that can be unrolled for privacy.

Standing in the treehouse, the wow effect is almost enough to make you forget the durian party you probably just had. Almost.

To minimise environmental impact, solar panels are used to generate electricity. The water pump relies on kinetic energy, instead of electricity, to pump fresh spring water uphill from the foot of the farm.

For raw material, abandoned old kampong (Bahasa Melayu for “village”) houses were disassembled, transported to their current location plank by plank, and repurposed into the lodges.

Opening their orchard to strangers was not part of the initial plan. "Green Acres was intended to be a holiday home for us and we built the lodge as a resting place after working the farm," says Kim.

They made the foray into hospitality when they realised it could be a viable stream of income during the months when durians aren’t in season.

"Durian season is only about three months a year. There's little income for the rest of the year. That's why a lot of farmers have quit. We thought, what if you could create a business model that brings in additional revenue? Maybe we could get young people who have traditionally shunned farming to reconsider farming as a profitable vocation," says Eric.

Anyone unconvinced need only look at the Chongs’ glowing good health for proof. "Here, the air is cleaned by the leaves. The water is filtered by the sand. So now we only need to worry about the food we eat," says Eric. "We had a medical check-up recently and the doctor said, ‘Whatever you're doing, keep doing it!’"

Green Acres doesn’t use chemical pesticides or fertilisers on the farm, thus minimising pollution to the surrounding environment.

It is also committed to sustainable tourism, using reclaimed materials to build the facilities, and electricity generated by solar panels.

The Chongs hope to show that agritourism is a viable path forward. Every tourist visit to the farm, allows the Chongs to continue to do their work.

Visit Torajamelo

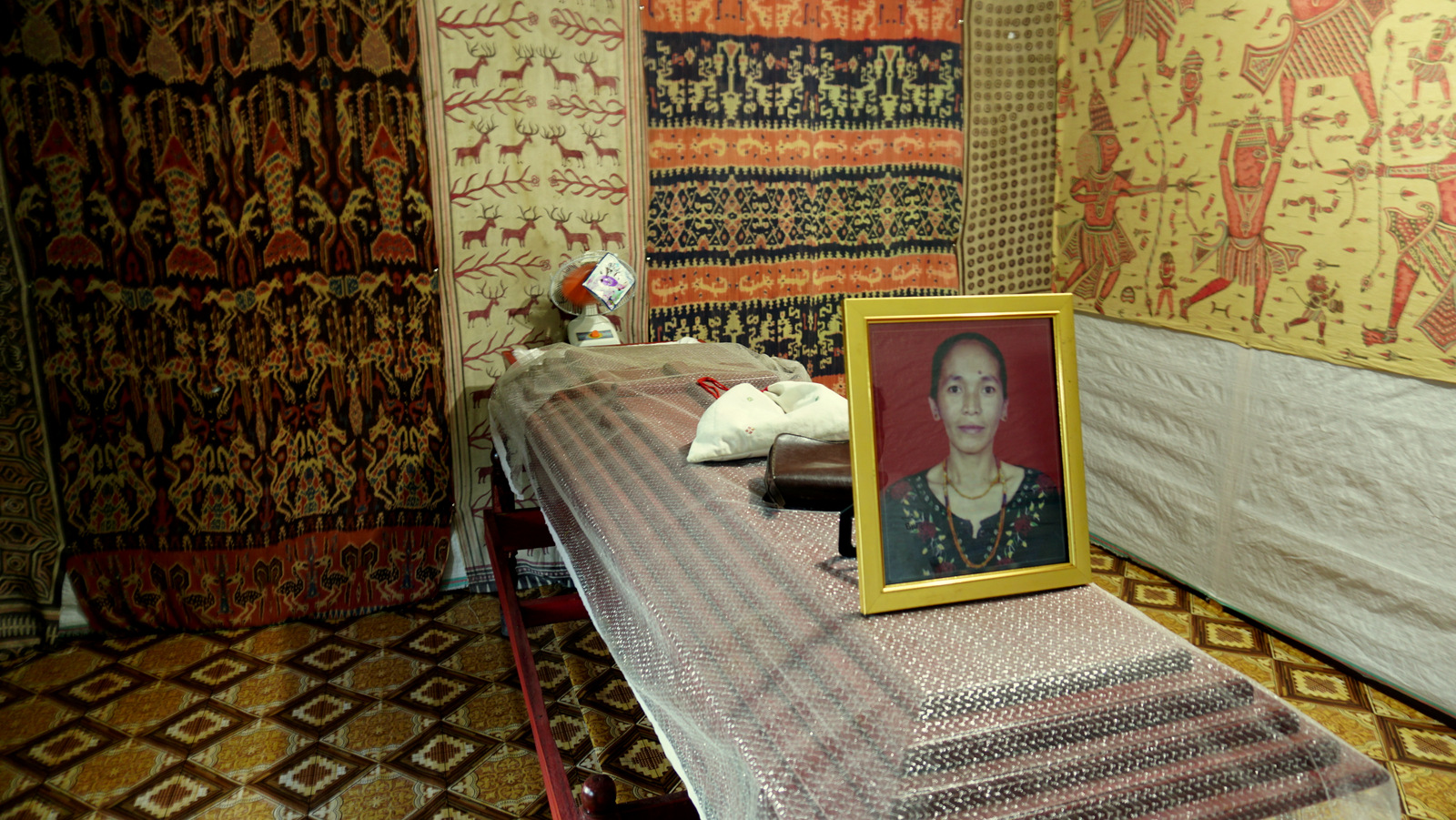

Famed for their elaborate rituals honouring the dead, a trip to Toraja is an adventure set in the highlands of South Sulawesi. Now through Torajamelo, you can stay in the homes of locals to experience the community’s heart and soul, while supporting their fledgling livelihoods in tourism.

MEET MERI AND THE TORAJANS

When Meri is able to bring a pig to every ceremony in the community nestled in the mountains of Toraja, her hallowed dream will be fulfilled.

One of many weavers living in this region, Meri’s dream echoes that of many in her unusual community, whose culture would strike even seasoned travellers as a world apart.

Elaborate funerals, amongst other rites and rituals, have become the way of life for the 450,000 inhabitants — an indigenous ethnic group also called Toraja — on this land in South Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Pig and water buffalo offerings are the main currency of exchange during these events and a stern label of your social prestige in the community.

The community blends Christian beliefs, as brought in by the Dutch missionaries in the early 1900s, with local religion known as Aluk to Dolo or “Way of the Ancestors”. Living 14,000 feet above ground, this mountain tribe has stuck firmly to its ancient roots, spanning generations.

But in a place where the dead are exalted in grand ceremonies, female empowerment, which has long taken a backseat, has been quietly making inroads. And I was here to see this for myself, even as I took in Toraja’s colourful culture.

#SOULFULTRAVEL

Toraja has long been a magnet for adventurous travellers, but the benefits of tourism has not always trickled down to the community as a whole.

“Most of the tour guides and agents were coming from outside the region, like Bali and Makassar, and the money was not coming back to the community. And with that, the special traditions and stories of this community were also being diluted,” shares Dinny Jusuf, founder of social enterprise Torajamelo.

Determined to do it differently, Dinny, who was already successful in helping women weavers in the Sa’adan region find an international market for their handcrafted products, joined hands with the local Tourism Village Association in Suloara’. Together, they ventured into community-based tourism.

Under this initiative, dubbed #SoulfulTravel, Torajamelo’s weavers and participating villagers earn additional income by renting out their homes and offering tours that may include traditional home cooking and learning the local dance.

Arriving at the village, I am greeted by stunning views of the green, hilly landscape, and the sound of rooster crows and chuckling children in the background. I felt as though I was on the cusp of an adventure in a strange new land, yet in a welcoming embrace that felt like home.

The homestays are simple but cozy, and some are fitted with amenities like western-style toilets. Those seeking a less rustic experience can choose to stay with Dinny at her house, Banua Sarira, at Batutumonga, a villa hugging the mountainsides of Toraja amidst sweeping rice fields.

Less than a year since the venture was made official, Torajamelo is seeing results, with participating Torajans gaining a sense of agency through improved economic circumstances and sense of dignity, especially among the women.

Arriving for my weaving workshop, I was greeted by weavers who were initially reticent, their reserve only dissolving when they demonstrated their skills.

Over coffee and kue, we overcame the language barrier to learn more about each other. I was amazed at how delicately they managed both technique and artistic flair, and how earnestly they passed on these skills to their daughters — who in turn skillfully balance their school work with this traditional art of weaving.

Says Dinny, “The weavers are proud to share their culture with guests from abroad. They find it useful to transfer their skills in communication, financial literacy and leadership skills in this new context. Plus, they can now sell directly to the tourists and earn additional income.”

An ex-banker from Bandung, Dinny’s connection to Toraja is a personal one — her husband is Torajan nobility, whom she met and fell in love with during one of her trips.

Staying with Dinny is akin to staying with a friend: she is happy to engage in conversations under the stars of her second floor verandah, sharing intimate insights into the traditions of the Toraja community.

The key to Torajamelo’s success has been keeping the community at the heart of its mission. “As long as the community remains at the core of this venture, and we keep them involved in all our programmes, we can stay authentic,” says Dinny.

HEAD IN THE CLOUDS

The Toraja landscape boasts scenic mountain views and wobbly roads opening up to rice fields and boat-shaped roofed ancestral houses called tongkonan.

There are no postal codes. Clans still live together in compounds. These houses are built with bamboo and raised from the ground to reduce the impact of frequently-occurring earthquakes in the area.

Rice is the subsistence crop, and the harvested rice is stored in special “rice barns” — carved and painted with traditional motifs like the buffalo or the sun, telling a story through the symbols.

Travelling on an itinerary planned by Torajamelo, I dove into diverse facets of the community. Cultural music and dance performances. Visits to the workshops of the traditional weavers, woodcarvers and coffee planters.

Soft spoken by nature, every person greeted me with a smile and a friendly handshake, locking my attention with gentle gazes as they shared their unique practices. Unlike many other places I have travelled through, there was no touting at any point of the tour — which I was told stems from the proud Toraja culture.

Torajamelo also designs tours according to individual preferences, catering to its diverse spectrum of tourists. The tours have attracted the likes of Indonesia’s Master Chef, William Wongso and film actress, Christine Hakim.

Dinny is working closely with the newly reorganised local tourism board, which has recently set up the Tourism Information Center dedicated to boosting tourism in Toraja in a healthy and harmonious way.

The last thing they want is to attract travellers who are just in Toraja to “tick boxes on their tourist trails, and have no interest in understanding the community or nature”, says Dinny.

AT DEATH’S DOOR

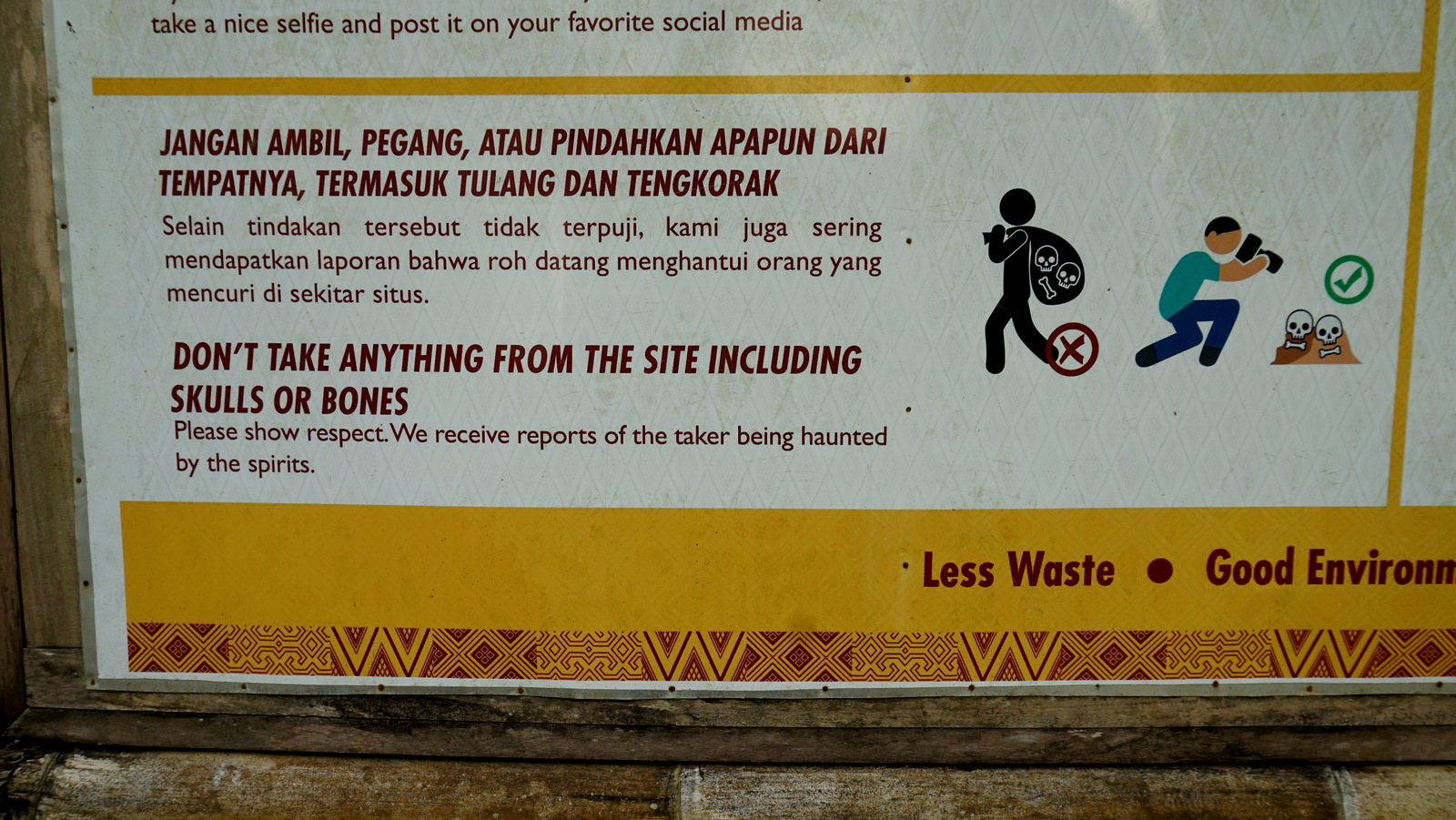

No visit to Toraja is complete without a visit to the local market, and the many graves sites that dot the region and form the centrehold of the community.

Toraja’s death rites are a big draw for travellers, who feverishly take photos as the Torajan go about their business, unperturbed by the attention.

Tipped by Dinny on a funeral gathering nearby, I venture to see this for myself, though not before I am given a primer on the significance behind the elaborate rituals, which can cost anything between US$50,000 to US$500,000.

When a Torajan dies, the body is embalmed as funeral preparations can span months as the family saves enough money for the rituals. The funeral, when it happens, can go on for days, with sacrifices of pigs and water buffalos, processions, chanting, dancing and feasting.

The meat from the animals sacrificed is divided among the guests to take home, and the government receives taxes on the animal offerings.

After the funeral, the bodies are buried in stone graves carved into cliff sides, and marked with wooden effigies meant to protect the deceased.

Every few years, families gather to clean the graves, where the dead are taken out of the coffins, washed, and dressed in fresh garb.

After the ceremony, when the sensory overload wore off, I could not help but feel slightly envious. While I grapple with urban existentialist tendencies, here is a community deeply in tune with their ancestors, holding firmly to their belief and values, celebrating life and death in perfect unison.

Not every traveller gets the chance to attend a funeral here, and I consider myself very fortunate. All I can say is, be respectful, be mindful. And always carry a black shirt whilst travelling in Toraja, in case you are invited to a pesta orang mati — a party for the dead.

Torajamelo works in partnership with PEKKA — The Association of Women Headed Households — to train and help market the weavers’ hand-woven products outside the local market.

Founded in 2008, Torajamelo works with a community of around 1,000 weavers in Toraja & Mamasa in Sulawesi, and Adonara & Lembata in East Nusa Tenggara. In Toraja, it now has over 100 women weavers earning a sustainable income of about of 3 to 5 million rupiah (US$197 to $328) a month.

The collective, located in the Sa’adan region of North Toraja became self-sufficient in early-2015. Women who had to leave their families to work in other parts of Indonesia or Malaysia are returning home as they are now able to earn a sustainable livelihood with weaving.

With community-based tourism, their incomes can be boosted further. At the same time, the interaction between the Toraja community and foreigners allows the beauty of the local culture to be preserved and shared globally.

Visit Lost Paradise

An eclectic and eccentric home away from home, Lost Paradise Resort offers an escape from the bustle of downtown Penang. But what makes this resort extraordinary is that owners Dr Chew Yu Gee and Melody Chew run an inclusive school right in the middle of it, where children with special needs learn alongside their mainstream peers.

MEET THE CHEWS

Their love is palpable. Not just for each other, their children and grandchildren, and long-time friends who work at Lost Paradise. But also for the people they help in their community. From the less fortunate to the marginalised, the young and the elderly.

A shared passion for making a difference, among other reasons, has united them for more than 30 years. And it is clear they are a match made in heaven — they finish one another’s sentences and tease each other with ease and charm. More significantly, they support one another unquestionably: Melody with her school, Dr Chew with the resort and his medical practice.

Together, they have nurtured a partnership doing good, at home and at work — a fine line, in this couple’s case.

ECLECTIC STYLE, WITH HEART

If it feels like you are experiencing a psychedelic epiphany when you arrive at the resort, do not panic. Lost Paradise is a rainbow-draped sensory overload; a long-lost, Southeast Asian cousin of Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory. Without the candy.

You might spy influences from Minangkabau and Balinese architecture; an enthusiastic flourish of batik furnishings; technicolour wallpaper, tiles and flowerpots; heavy, Majapahit-period wood furniture; intricately carved doors shipped in from Bali; collectors’ pieces from India and China; and art made from recycled materials.

After giving your senses time to acclimatise to the explosion of colour and the hodgepodge of designs from various cultures, you will likely be in the right frame of mind to appreciate how idyllic Lost Paradise is.

The Chews built the seafront property as a home for their family of five children, who have since left the roost. The confluence of colour, textures, materials and cultures reflects Dr Chew’s effervescent personality.

“Most people cannot understand the theme. It doesn’t fit a pattern, but it’s very interesting.”

Dr Chew Yu Gee Co-founder, Lost Paradise Resort

“A piece of art is appreciated in its own way by a person. To somebody it’s horrible, but hey, it looks good to me,” he explains, with a laugh.

THE “RELUCTANT” HOTEL

Dr Chew calls the resort a“reluctant hotel”. Their home was never meant to welcome strangers to enjoy its peaceful grounds and unobstructed views of the Malacca Strait.

But health issues forced Dr Chew to find another source of income, besides his medical practice. This was so Melody and he could continue to fund the school, Lighthouse Academy, in the resort.

They opened their doors to paying guests in 2014.

“We didn’t have to stay in such a big place, we could rent (the house) out, and it could be sustainable. So we vacated our house,” explains Dr Chew. “We stayed above the school. It was noisy, we didn’t have any privacy, but it was okay. The hotel took off.

“I know now if anything happened to me, it can support the school.”

A SPECIAL SCHOOL, FOR SPECIAL STUDENTS

It’s 8.30am, and the resort’s quiet is broken by the squeals and laughter of the Academy’s pupils splashing in the pool.

For those who baulk at the idea of sharing a holiday with excitable children for about 30 minutes every weekday morning, the Chews suggest choosing another hotel. Mind you, they are not being rude, just honest, as you will not find a couple with bigger hearts this side of Batu Ferringhi.

Says Dr Chew, “To us it’s happy laughter, but for the rare few, who don’t like it, we have refunded their money.”

If you like the notion of contributing to the education of children with learning and developmental challenges, and from marginalised communities, then consider unpacking your suitcases and unwinding at Lost Paradise.

Melody, a former teacher from Singapore, says some guests, who warmed to the idea of the school, have even helped out in classes.

Dr Chew also operates a free children’s clinic in his home, for patients who mostly come from less fortunate backgrounds - often the children of fishermen from Batu Ferringhi and nearby suburb, Telok Bahang.

FINDING PARADISE

Still, you’re at Lost Paradise to relax and put your feet up. And there are plenty of ways to do this.

Beautiful landscaping, including a wide variety of flora and fauna, a particular source of pride for Dr Chew, creates a perfect setting for this to happen.

The rooms and suites are spacious, and most have fantastic views. You’ll be sure to sleep like a baby in the comfortable beds. And if you don't mind a few mosquitoes sharing your space, let the sea breeze envelop your room, and awake to the sound of lapping waves.

During the day, spend a leisurely afternoon lazing by the pool. Or reserve a spa treatment in advance, to relieve those tense muscles in the comfort of your room.

For the more active, there are kayaks to take out and other sea activities, such as windsurfing and sailing. Dr Chew says otters sometimes visit at dawn.

A taxi will bring you into the centre of town in 20 to 30 minutes. If you prefer to stay in, you can order delivery, or you could ask to use the kitchen to whip up a meal — one of the perks of being a guest, albeit a paying one, in someone’s home.

Dr Chew says one Dutch couple, who were long-term guests, grew so comfortable they used the main kitchen to cook for staff. “They will help clean the pool, cut the grass. They treated Lost Paradise like their own home.”

A HAPPY HOME IS A HAPPY PLACE

Set against the shifting tones of the open sea, and framed by coconut and palm trees, sand between your toes and tinkling wind chimes, this ‘home away from home’ does have the makings of a lost paradise.

Granted, it might not be to everyone’s taste. But while the characters of this tropical stage keep changing, what remains constant, is the warmth of family and friends from all corners of the world. And that, in this traveller’s books, is paradise.

Visit Grassroutes

In Walvanda, a verdant hamlet inhabited by the Warli, a rustic way of life has quietly survived amidst the pressures of modernisation. Spend a day there taking in their distinctive art and the joys of rural life, and help the Warli preserve their traditions.

MEET THE WARLIS

As you trundle into sleepy Walvanda, you can’t miss the fifty and more shades of green — a mesmerising landscape created by a sea of paddy fields, lush and green after the monsoon rains.

Located in the state of Maharashtra, it’s just 130 km from the hectic metropolis that is Mumbai, but it feels like a world away.

Literally, for Walvanda is home to the indigenous Warli tribe, who have managed to hold on to some of their beliefs, customs and language, despite the pressures of urbanisation.

It is also one of the few places in India where you can watch them create their distinctive art, with which the tribe shares its name.

This sense of being enveloped into a new world and a different culture is evident from your arrival in the village.

Waman, a guide from the village welcomes you, not just to his home, but to the village — because you are the guest of the entire community.

He applies a tikka along the length of your forehead as a sign of a good omen, and you are handed a flower and a “Gandhi cap” to don on for the rest of your time in the village — just like the locals do.

THE LIVES BEHIND THE ART

Look up “Warli” on the Internet, and you are likely to be inundated by images of their richly-detailed art. A form of pictorial storytelling, the paintings are an avenue for the tribe to impart their way of life — from important traditions and beliefs to the minutiae everyday life — through the generations.

A visit to Walvanda, organised by social enterprise Grassroutes, is an invitation to look at the lives behind the art.

Leaving behind your shoes at the main entrance of the house, your host family readies you to start the day right — with breakfast.

Poha — dry flakes of flattened rice — served with roasted groundnuts and a lemon wedge, is the staple breakfast in most parts of Maharashtra and Walvanda is no exception. Over a cup of piping hot tea (another favourite of the locals), Waman outlines the activities of the day, while the host family chimes in with tips on what to watch out for.

After breakfast, a local artisan adept in Warli painting guides you through its creation process.

Traditionally, rice-paste, gum and water would be mixed together to make the paint, and a chewed bamboo stick served as the paint brush. For centuries, the red-ochre walls of the houses — built from cow-dung and mud — served as the canvas.

But modern life has chipped away at this practice: acrylic paint and actual canvas are used today, as mud houses have been replaced by their brick-and-mortar counterparts.

In the past, Warli painting was an important ritual of village life, undertaken during important ceremonies like marriage or harvest time. The distinctive geometric patterns and brushstrokes served as the medium through which Warli culture was passed down through generations.

But now, Warli art is only practised by a few in Walvanda and other villages in the region, with pieces created mainly for exhibition or for sale.

A walk through the village with the host reveals more nuances of the Warli way of life. Agriculture is the main source of livelihood for the tribe, and rice — so integral to Warli painting — is the staple kharif (monsoon) crop.

The gentle rhythms of working the land and gathering this precious crop fill the village, from the sway of the lush green fields, to the swish of rice being husked, to pounding of rice being milled by hand in rooms found in every Warli home.

For city-bred folk like us, who are used to seeing polished rice in its final form in shops, witnessing the effort involved in growing and harvesting the rice can be eye opening.

Another plant cultivated is bamboo, which can be used to make ghungda — a mesh that serves as a protective covering for farmers during monsoon season.

Waman explains that the villagers had started using plastic sheets a few years ago, but have once again returned to tradition: “We’re slowly making a return to the ghungda after we saw how it has remained a practice in Purushwadi (another village working with Grassroutes). We realise plastic isn’t a sustainable option.”

A WAY OF LIFE, A WAY FORWARD

Like many indigenous communities, the Warlis are caught between maintaining their authentic ways and adapting to the ever-changing macro-environment.

Learning to speak English, picking up basic computer skills and working 9-to-6 shifts have come at the cost of letting go of their inherent way of life. Some have chosen the “practical” course, by taking up government jobs that guarantee employment, for example.

Enter Grassroutes: a social enterprise that promotes rural tourism to create livelihood opportunities for rural communities such as Walvanda.

“While many tourism initiatives are trying to create a market for the locals in a particular region, it is the outsiders who end up taking control, (while) the locals are left to do the menial jobs,” says Richa Williams of Grassroutes.

Grassroutes emphasises community involvement, by building a rapport with the gram panchayatsthat govern rural villages.

A village tourism committee is formed to ensure maximum involvement from all households, and locals are trained in hospitality skills, thereby giving them a source of livelihood without having to renounce their indigenous ways.

It currently works with close to 600 rural families across four states in India. These households have seen their incomes go up, while fewer have chosen to migrate to urban areas for work.

“All our projects have been self sustainable within two years of functioning.”

Richa Williams, Grassroutes

And there is a sense of pride felt by the community too, in seeing their traditions in the spotlight.

Shares Waman: “A few years ago, a journalist had visited our village with his wife, who unfortunately happened to get stung by a bee. She was both scared and in pain. It was a paste of two medicinal leaves which when applied to the inflamed area provided her with immediate relief. He (the husband) went on to write about it for the newspaper he was working with!” Leaving Walvanda and watching the emerald green fields disappear in the rear-view mirror, one may be struck by the intriguing lesson on sustainability the village offers.

Their farming processes may appear “inefficient” to modern eyes, but they produce enough for their needs, let nothing go to waste, and do minimal harm to the land.

They own little by way of material possessions, but they are the masters of the land they live on.

Time takes on a different quality in Walvanda, and it is tempting to write it off as a “throwback” and a relic of a bygone era.

But even as the Warli adapt modernity into their lives, perhaps they still have a few lessons in store for modern world, after all.

Grassroutes supports rural communities such as Walvanda in developing tourism as a way to earn an income, so that villagers would not need to migrate to urban centres to work and live under harsh, sometimes exploitative, conditions.

Through its tourism initiatives, the average annual household income of communities engaged by Grassroutes has grown by 25 to 30 per cent.

Meanwhile, local culture is preserved, while the tours give urbanised travellers a chance to understand a different way of life.

Your visit gives rural communities a chance to pass on their traditions, while earning a living.

Visit SaveAGram

If waking up to birds chirping, enjoying fresh home-cooked meals and being surrounded by nature is your thing, then explore a homestay with SaveAGram in Kerala. Your visit will leave you feeling rejuvenated, and your stay will help empower the villagers hosting you.

MEET THE NAMBIAR FAMILY

“These are villages that God created in the best way possible.”

Amala Menon, Founder, SaveAGram

Kesavan Nambiar lives in his ancestral home in Wayanad, Kerala, with his wife Sumathi, their son Rijesh and daughter-in-law Sowmya, and granddaughter Niranjana. A forward thinking man, Kesavan grows all his produce organically. Working with the SaveAGram initiative, he has opened up his home and farm as a homestay, so that he and his family can preserve and share their peaceful way of life, while earning an income to better run their farm.

SaveAGram (gram is Hindi for village) was founded by Amala Menon to offer rural homestay experiences in India, thus keeping traditional village culture alive while providing host families with a source of income.

NATURE, CULTURE, FOOD

Awaken to the sounds of nature and step out for a leisurely walk in the morning mist. Explore the village and its surrounding forests, and you may even find a waterfall only locals know about. Learn about or even take part in local customs, or visit ancient temples. Come back home to a freshly-cooked meal by Sumathi, who uses organic produce picked from their farm to create mouth-watering dishes cooked over a wood-fired stove. Around the house, Kesavan cultivates rice, beans, pepper and other crops using organic methods.

You will live in Kesavan’s ancestral home, built traditionally and maintained with great care and attention. The simple but cozy house has two bedrooms for guests and a refurbished bathroom.

IMMERSE YOURSELF IN THE COMMUNITY

Wayanad is home to the largest population of indigenous people in Kerala, and a school was founded to provide free education to some 250 children, who might not otherwise go to school at all. Visits to the school can be arranged for you to spend time with them.

Not only will you empower the Nambiar family through the homestay so that they can continue with (and share) their way of living, your visit to the village school may even inspire you to do more, such as by volunteering to spend time with them.

Visit The Dorsal Effect

Explore Lombok’s natural beauty and laid back charm with a former shark fisherman who has hung up his nets in favour of guiding tourists, instead of hunting down the dwindling shark population. When you book an eco-tour, you support his new livelihood.

After we first told their story a few years ago, many like Eunice were inspired to go on these eco-tours. We also made a journey with The Dorsal Effect to take in the natural wonders of Lombok - and find out how it has changed lives.

MEET SUHARDI

He dives into the clear blue waters of Lombok, proudly guiding snorkellers as they take in the vibrant coral reefs.

It is a long way from his previous trade - shark fishing. Born and bred in Lombok, Suhardi became a shark fisherman when he was 10 years old.

He would go out to sea two to three weeks at a time, cut off from his wife and two children. As the relentless demand for sharks decimated their numbers, his income dwindled.

Fishermen have had to venture further to hunt sharks, which meant that each expedition cost more. Depending on the catch, Suhardi would take home around S$50 to S$200, notwithstanding the inherent dangers of being out at sea.

Now, working for The Dorsal Effect, “I can sleep at home every night with my wife and kids,” he shares. He has also saved enough from his four years as a guide to buy a second boat, which he uses to run a local boat taxi service for extra income.

And he loves meeting new people, and showing off the beautiful and pristine islands of Lombok.

DIVE INTO THE DREAM

A trip with The Dorsal Effect is both a venture into a dreamscape and stark reality.

As a guest, you will be taken on a boat to pristine snorkel sites and secluded beaches far away from the touristy areas, where you can swim in crystal clear waters amid healthy reefs. If you’re lucky, you may even spot sharks swimming in their natural habitat.

And you can choose to trek around scenic rice paddy fields and visit beautiful waterfalls in Lombok’s luxuriant rainforests. Meals consist of local delicacies such as nasi campur (mixed rice with vegetables) and yummy curries.

But you also visit Tanjong Luar market to see firsthand the shark trade, and learn how precarious it is for both the sharks and the men who hunt them, as the trade is increasingly unsustainable.

And you see the pitfalls of tourism, when you see how little care other tourists take when traipsing through the islands. During our trip, we saw some guides and tourists on other tours picking up corals from the sea floor, to pose for pictures.

You also learn how to not just enjoy, but also respect the environment - Suhardi, unlike other boat operators, only lands his anchor on sand, to ensure that the coral reefs are not damaged from the boat tours.

THE ONE WHO STARTED IT ALL – KATHY

An ex-secondary school teacher from Singapore, Kathy’s passion for the environment and dismay over shark trade spurred her to start The Dorsal Effect. Her solution? Persuade shark fishermen to earn their livelihoods as eco-tour guides, and save sharks from being hunted down for their fins.

“When you see sharks in their natural habitat, I think there is a point where something would change in you and you really want your future generations to able to experience that as well.”

Kathy Xu, Founder, The Dorsal Effect

Booking an eco-tour could help fulfill Kathy’s audacious dream - to get more shark fishermen to switch to leading such eco-tourism tours for a sustainable income.

Demand from responsible travellers like you encourages fishermen to consider eco-tourism as an alternative to hunting sharks for income.

In the long run, this could improve the situation for the shark population in the region, and result in a healthier marine ecosystem in and around Lombok.

People doing good. Causes you can support. Subscribe for a weekly dose of inspiration.

Our Better World is the digital storytelling initiative of the Singapore International Foundation, which brings world communities together to do good.

Our Better World is the digital storytelling initiative of the Singapore International Foundation, which brings world communities together to do good.