Meet Nash, Rumah Tiang 16 host

Nash is the founder of Rumah Tiang 16, a boutique homestay in Lenggong, one of Malaysia’s four UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Nash is the founder of Rumah Tiang 16, a boutique homestay in Lenggong, one of Malaysia’s four UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

“My dream is to see Lenggong become a model of community-based tourism. I’ve seen many examples of how tourism done right can bring prosperity to a community, and my hometown has so much to offer the world!

Because of my extensive exposure to hospitality with fine hotel brands for almost two decades and my own travels, I learned that culture is something that people cannot copy. I believe that promoting a cross-cultural experience is an important pillar of tourism.

As a Pattani descendant, I try to inject cultural elements into the whole Rumah Tiang 16 experience. For the past few years, I’ve brought in locals to share their skills and knowledge in heritage crafts.

Out of the nearly 300 guests of 25 nationalities I’ve hosted, 90 per cent are from other ethnicities. They are always curious about life in a traditional Malay kampung. I’ve seen the delight in their eyes when they try their hand at weaving, making bedak sejuk — a traditional Malay skin powder — when they’ve experienced a true forest-to-fork lunch, or the simple act of sarong donning! Many guests become self-appointed ambassadors, promoting Lenggong after the Rumah Tiang experience. This is my ‘booster jab.’

By showing locals that their traditions and heritage is invaluable, and considered a treasure by outsiders, I hope to encourage the younger generation to learn and inherit this precious heritage, turn it into a sustainable living, and carry it into the future.

I am very lucky to come across a few families who are willing to share a piece of their lifestyle with visitors. Without them, I would not be able to come up with the quintessential Rumah Tiang 16 homestay experience that showcases the “stars” of Lenggong in archaeology, anthropology and ecology.

Kampung folks are usually very shy. They don't have much, but they have enough. With rice and salt at hand, people in the rural area can survive. For their protein, they can just catch some fish or do some trapping for bush meat. The locals feel very happy that people from the world over come to experience the little things that they have.

I truly believe the very essence of a nation lies in the pockets of the pockets of the rural population, in the interior, not in a big metropolis.

Mak Ani serves sumptuous forest-to-farm home cooking at Rumah Tiang 16, a boutique homestay in Lenggong, one of Malaysia’s four UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

“The first time I met Nash was in 2019. He came over to my neighbour Mak Lang’s house because he wanted to see how she made atap rumbia (thatched roof). It is a craft that requires skill. After that, he brought two guests who wanted to learn from Mak Lang. That was how I knew that Nash was the son of a Lenggong teacher, and after being overseas many years, he wanted to create tourism awareness amongst locals.

After that first visit, he continued to bring more people. Somebody in the kampung would provide lunch while Mak Lang would serve the guests a sweet at the end of the meal, cendol sagu rumbia. I provided the sago using our harvest from sago palm trees in our garden.

Then during one of the visits, Nash’s lunch caterer couldn’t make it. He asked me if I could do the cooking that day so that he could bring them over to my house instead of taking the guests to another place.

Honestly, I panicked a little at the beginning. I had nothing fancy to serve the guests, no meat or chicken. But Nash told me, ‘No need. The guests are interested in eating something traditional, kampung cooking.’ He told me to just cook what my family eats, using whatever I have. So that’s how we began. We initially started at an old dangau (shelter) in my orchard that seats only a few people. Later we expanded it to cater for groups of 20 to 25 people.

I really enjoy having guests come to my home. It gives me so much pleasure to see people from all over the world enjoying dishes that are unique to our kampung such as ikan pekasam, gulai rambutan, sambal nyior, masak lemak and many more. I learnt these dishes from my mother and grandmother before I got married.

I have not worked outside, as my responsibilities as a mother and homemaker take up all my time. In addition to taking care of my five children, I also look after our orchard, where we plant fruit trees, herbs and vegetables for our own consumption. One of my daughters helps me with the cooking for Rumah Tiang 16, so I get to pass on my skills and knowledge to her.

Before Nash came into the picture, we didn’t have many visitors to Lenggong even after the UNESCO award was given. Nash explained that his intention was to introduce Lenggong to the outside world. He said that we have a lot of history and culture and by sharing it, we can preserve the future of Lenggong. When he started, there were naysayers. But now they can see with their own eyes, there is a regular stream of visitors from both local and overseas.

I am happy I got to play a part in this change.

We started working with Nash in 2019, but had to stop during the pandemic for more than a year. During that difficult period, we had to survive on my husband’s pension. Now that the borders have opened again and we are back in business, the extra income enables me to treat my family, buy clothes and give pocket money to my six grandchildren when they come back to Lenggong.

We are very thankful to Nash for helping to bring all the visitors to Lenggong. We nicknamed Nash the tourism ambassador of Lenggong. I hope we will continue to work together so that our community will benefit from tourism and our town can prosper.”

In Long Mỹ, a village in Vietnam's Mekong Delta region, Phan Thị Nga and her childhood friend, Chiêm Thị Bé, are working on a batch of colourful patchwork cushions destined for customers from as far as Europe.

As they work, Nga recounts a time in Long Mỹ when travelling on xuồng, local-style wooden boats, was a daily occurrence. "We used to bathe and even cook using the river water, now no one would dare do that," she exclaimed with a laugh, referring to the pollution that has swept the waters.

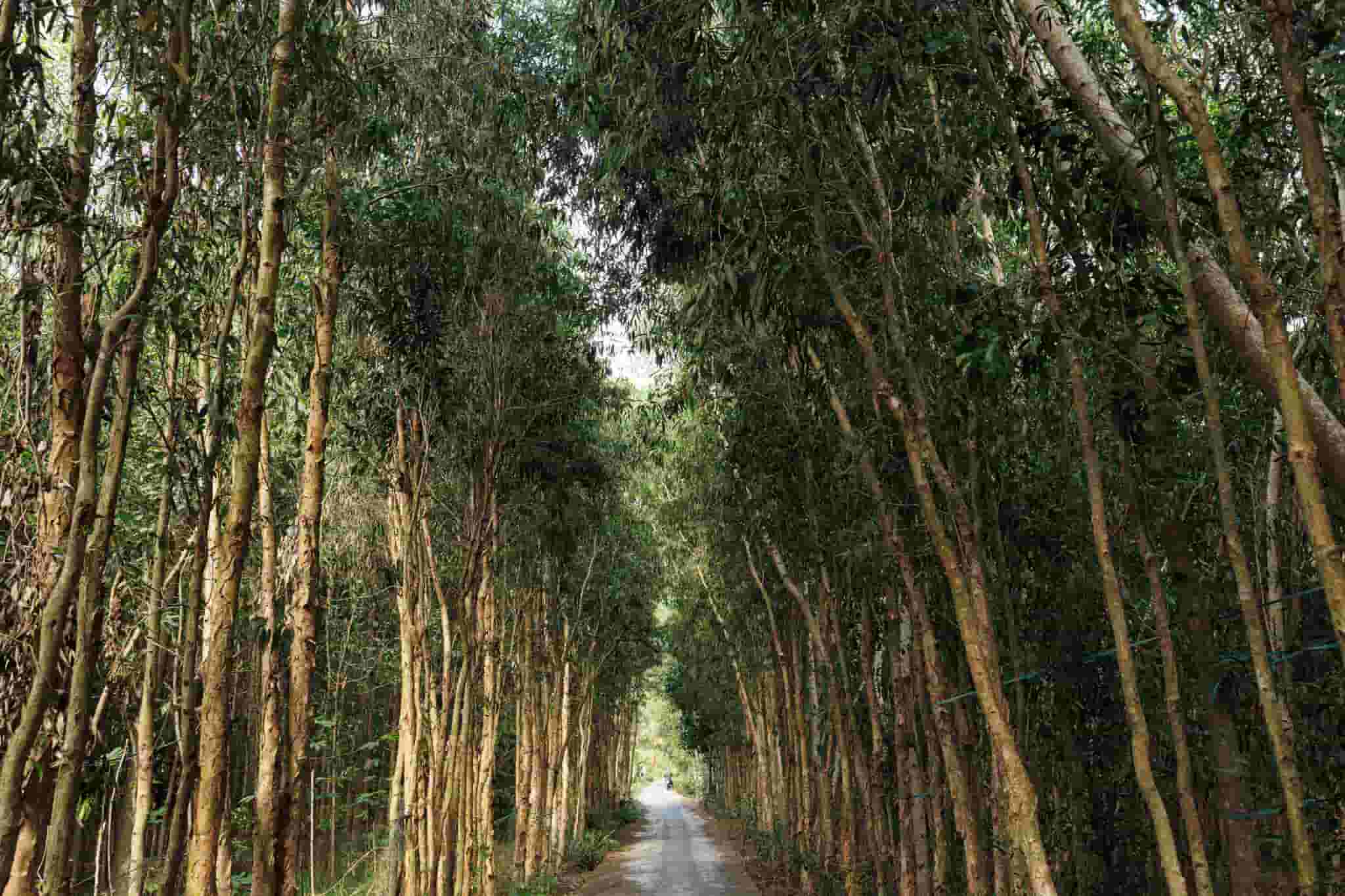

Located in Hậu Giang province, water still flows into Long Mỹ from the grand Mekong itself, forming countless tributaries and streams, flanked by rows of Flame of the Forest trees.

But the picturesque setting hides decades of poverty from casual eyes. As the land becomes less suited for farming owing to unsustainable farming practices and pollution, the flowing streams leave villagers, who cannot afford their own transport, stranded from schools and other services that might lift them out of poverty.

For women like Nga and Bé, crafting quilts for Mekong Quilts, a social enterprise that creates sustainable work for underprivileged women, was a boon to their fortunes — until orders dried up.

The COVID-19 pandemic’s halt on international travel meant the end of demand for the women’s intricate quilts, which were highly popular with travellers.

But sustained by a small stream of online orders and a pivot towards making new products like face masks, Mekong Quilts, which still operates one shop in Ho Chi Minh City, has held onto its mission to uplift the community.

And as travel gradually resumes, Mekong Quilts is now also running cycling tours to the Mekong Delta, where visitors can get to know the communities behind the crafts.

Nga belongs to the first batch of women trained by a British fabric designer when Mekong Quilts first started in 2001. “[Partly] because I love the job, and because of my previous experience as a seamstress,” Nga says, recounting how she came to join Mekong Quilts.

“Many [of the ladies] saw me making quilts and asked to join and learn the craft!”

Extremely passionate about quilting, she explains the labour-intensive process: "We soak the fabric [in soap water] for one day before drying for another day. After that, we iron all the pieces of cloth to make sure the patterns are well-aligned.”

Larger details are then completed using sewing machines, with smaller details and patchwork finished painstakingly by hand.

"Once [the quilts are] finished, we wash them one more time!" says Nga, who is now the leader of Mekong Quilts sewing team in Long Mỹ village’s Thuận An ward. She hopes that demand recovers as the pandemic dies down.

Adds Bé: “Quilting work gives us stable work. It also gives us voice in the household. Without it, many of us [women] would need to go to Saigon to work.” She notes that it would also be “very difficult for kids to stay in school”, as they may need work to support their families.

For poorer families in the region, traversing 'monkey bridges’, or cầu khỉ, as the locals call them, is an everyday ordeal. Life without a motorbike may mean being trapped in a never-ending cycle of poverty.

In 1994, when Bernard Kervyn founded NGO Mekong Plus — the parent organisation of Mekong Quilts — funding the cost of building better roads and bridges was top on the list of priorities.

"Accessibility means children can go to school and stay in school," says Bernard, who worked in the human rights sector before starting Mekong Plus.

Mekong Plus offered to fund up to one-third of the cost of construction, but early efforts were stymied by a lack of support from local authorities. “We finally arrived in Long Mỹ, and established a long term working relationship with Ánh Dương centre, an independent NGO that shared similar ideals,” shares Bernard. Since the 1990s, Mekong Plus has helped construct at least 10 to 20 bridges and about 20km of rural roads annually.

Then came Mekong Quilts, which was started as a social enterprise to create employment for local women. “Providing the mothers with work means the children can stay in school,” Bernard notes.

So far, over 150 women from the Mekong Delta have been engaged as artisans, who are paid for each item they create — a product range that before COVID-19 included festive papier-mâché hangables to water hyacinth fibre tote bags. Mekong Quilts was such a success that the social enterprise was able to open five shops in Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi, Hôi An, Siem Reap and Phnom Penh.

Before the pandemic, Mekong Quilts was able to fund a scholarship programme with its proceeds. Due to the Mekong Delta’s remote and difficult terrain, distance and the affordability of basic transport can be hurdles to a child's education. “The average cost of keeping a child [from the Mekong Delta] in high school is almost VND12,000,000 (US$530) a year,” Bernard notes.

The scholarship programme has helped the families of youth like Nguyễn Văn Huynh, who is now working remotely for a European company; his sister Nguyễn Thị Huỳnh Như has managed to continue her schooling.

Mekong Quilts was also able to modestly contribute to Mekong Plus which runs programmes to improve access to healthcare, education and microfinance opportunities for underprivileged communities in the Mekong Delta. For example, the micro-credit schemes help locals to start small-scale pig, eel, duck egg and even straw mushroom farming projects.

‘Brother’ Phạm Thanh Trần, one of Ánh Dương's farming experts, describes how locals with little land can farm straw mushrooms for a quick turnover. A single stash of straw can produce up to US$30 worth of mushrooms a month, using less than a sqm worth of space.

As the pandemic worsened, Mekong Quilts’ quick-thinking team, not willing to simply wait for work to dry up, were able to launch a line of hand-sewn triple-layer fabric masks with eye-catching designs, several of which feature traditional batik and Hmong indigo fabric acquired sustainably from tribeswomen.

The masks helped keep the artisans employed as quilt orders dropped 60 per cent by June 2020. "We began focusing on baby quilts, cushions and also, fashion," Hồ Tiêu Đan, a long-time volunteer, added.

Although less than half of Mekong Quilts’ pre-pandemic headcount of artisans remain working regularly, the social enterprise has managed to stay afloat.

“We make about 1,000 masks every month [now],” shares Út. “Many of us have returned to working in big factories or in the fields but at least there’s still work to do.”

Meanwhile, Mekong Quilts’ bamboo bicycles are finding a growing audience.

Designed by Bernard with Alain Kit, a French bicycle designer, the bicycle takes advantage of the abundance of bamboo in Vietnam. “Except for the wheels, tyres and joints reinforced by hemp fibre and epoxy, the bicycles are fully bamboo!” Bernard says with pride.

At its peak, Mekong Quilts’ bamboo bicycle workshop kept nearly 20 craftsmen and women employed. Currently, only four remain, as the pandemic has driven down demand.

In the last few months however, cycling tours — when allowed by the authorities — on these bikes have helped to support Mekong Plus. Cyclists can visit Long Mỹ over a two-day trip where they see a side of Vietnam that is often overlooked amid the rapid transformation of the country.

First organised in 2014 for donors of Mekong Plus, the trips have become popular since Mekong Quilts opened them to the public, generating some US$2,780 in the first six months after tours were allowed to resume. “[Beyond travelling costs], participants contribute freely to Mekong Quilts at the end of the tours, largely going back into our scholarship programme,” Bernard says.

Tours aside, Mekong Quilts hopes that more people are inspired by the beauty and the stories behind its crafts to make a purchase, while looking forward to Vietnam opening the door to international tourism, allowing more artisans to be employed. As volunteer Đan puts it: “It’s a gift that gives twice.

When you buy something from Mekong Quilts, you support a community of women who have been able to earn a sustainable livelihood close to home, instead of leaving their families behind to find work.

Consider also exploring the Mekong Delta region with Bernard via Mekong Quilts’ bamboo bicycles; proceeds go to Mekong Plus, Mekong Quilts’ parent organisation, which supports underprivileged communities with micro-financing, scholarships, and health, hygiene and agricultural education programmes.

I want to support Mekong Quilts

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases remain a concern, and various travel restrictions and safety measures remain in place across countries. During this time, we encourage you to respect prevailing rules and precautionary measures while travelling, and seek out experiences that support communities hit hard by the pandemic.

Nestled amid tall pines and lingering sea breezes – a hint of the sweeping beaches that await – Zambawood lulls travellers into utter relaxation almost as soon as they step onto the property.

But if the soft embrace of its breezy-chic villa doesn’t warm your heart, its mission will – the resort is also a training ground for youth with disabilities, where they can socialise and acquire livelihood skills.

The inspiration? The founders’ son Julyan, who will become a familiar sight over your stay, as he works on Zambawood’s organic farm, which supplies the resort’s meals. Diagnosed with autism at age two, Julyan’s transformation after he made Zambawood his home motivated the founders to open the property to more youth.

Like many other travel destinations, this slice of paradise-meets-empowerment was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic that swept the world in 2020 and 2021, leaving a wake of uncertainty and broken dreams.

Igmedio Jaco Jr recounts how his son John Rex felt when he learnt that he could not go to work at Zambawood’s cafe due to a COVID-19 lockdown. “He kept asking me when he can work again,” he said of John Rex, who has autism.

Yet Zambawood not only prevailed, it has grown. Founder Rachel Harrison has opened a second resort just 90 minutes from Manila: Julyan’s Garden, driven by the same ethos.

Sitting on the western shores of Luzon, Zambales is about four to five hours by car from Manila, nestled between magnificent mountains to the east and the serenity of the sea in the west.

Zambawood is located in the town of San Narciso, which is known for its beaches and surf spots. Originally the holiday home of Rachel and her family, the property was transformed into a resort after Rachel saw how her son Julyan was thriving on its idyllic grounds and becoming more independent.

Setting foot on the resort feels like coming home from a hectic day, and finding a space that has been lovingly arranged for your comfort and needs. The nearby beach offers a chance to tackle the waves or simply relax on its shores.

On the premises is an organic farm which is open to guests, a field of sunflowers, and a tree nursery where guests can plant seedlings and stay updated on their growth. In the evenings, Zambawood staff can organise a beach bonfire, complete with marshmallows and hotdogs ready for toasting as you take in the sunset.

Since it opened in 2014, the resort has become popular with families, and is a destination for wedding photo shoots and parties. “We want [guests] to feel good through the aura of relaxation,” says Rachel, a former flight attendant who trained as an architect.

With easing travel restrictions in the Philippines, the villa is now open and ready for visitors who wish to spend quality time with Zambawood’s signature warmth, good food, and relaxation fit for the physically and mentally tired.

An “aura of relaxation” was also what Rachel and her husband Keith sought for Julyan when they first bought the property. When Julyan was diagnosed, “it was as if our world stopped,” recalls Rachel.

Researching various methodologies to help Julyan, Rachel learnt about the positive effects of nature on people living with autism. This prompted the Harrisons to move to Zambales – to remarkable effect.

Before moving to Zambawood, Julyan had a temper and found it challenging to take instructions and do household chores, notes Rachel.

With the setting up of a farm on the property, Julyan was able to channel his energies to tending the farm, growing flowers, vegetables and fruits. He also became an avid painter, finding a new way to express himself by mixing colours and creating works of art, which soon filled the villa.

Encouraged by Julyan, the Harrisons decided to do more. Partnering local organisations in Zambales, the resort hosted on-the-job training programmes for youth. Behavioural therapists and instructors taught barista skills, arts and crafts, and skills in housekeeping, cooking and baking.

As soon as a student acquires the required skills and hours of training, Zambawood and its cafe, Julyan’s Coffee Spot, match the trainee with part-time jobs with the villa, the cafe or at partner establishments.

The pandemic put a stop to the training, and the resort and cafe closed in 2020. When at last a soft opening was held at Zambawood in 2021, the trainees were given rotating shifts to provide income and motivation. “It was very difficult telling them that they cannot report to work,” Jennifer Uy, the cafe’s manager shares.

Even as quarantine guidelines changed nearly monthly, baffling guests and staff alike, they held on. When dining in was not allowed, the staff switched to food delivery. “God will provide because we are helping,” Jennifer adds.

Among the returning staff is John Rex, 27. According to his father, Igmedio Jr, John Rex has the mental capacity of a seven-year old, but this has not hindered his ability to deliver good service to the table.

When he was asked to return, John Rex couldn’t contain his excitement. “He had his uniform prepared days before his schedule,” Igmedio shares. “He was really dedicated and he loves doing his housekeeping tasks there.”

At Zambawood, John Rex sweeps, washes the dishes and waters the plants. When he is assigned in front of the house at the coffee spot, his big smile greets every customer as he sets the table and serves the meals.

With Julyan’s Garden just 90 minutes by car from Metro Manila, the same healing and soul-refreshing wonders of Zambawood can now be experienced sans the long travel.

If Zambawood flaunts the sea, Julyan’s Garden boasts the mountains. At sunset, the Taal volcano and surrounding mountains glow, and the light changes as the staff sets up the best outdoor dining experience. Feast blissfully as you watch the parting sun, followed by the moon and numerous stars as you enjoy a glass of wine or hot coffee to ward off the cold breeze.

Healing and wellness through food is also a key feature, with a partnership with vegan restaurant Studio PlantMaed by Chef Mylene Vinluan Dolonius. Ingredients are harvested from the garden, prepared in front of guests and served with the same artistry and gusto as at Zambawood.

Instead of a villa, guests stay in artistically customised container units with all the creature comforts like air-conditioning. More adventurous guests can camp — staff will set up tents and bonfires while guests take in the stars.

As with Zambawood, Rachel remains intent on her mission to support the employment of people with disabilities. Among the trainees at Julyan’s Garden is Aguinaldo, fondly called Ging-ging, who is 28 years old and has Down syndrome.

When asked what he wanted to do at the resort, Ging-ging said he wanted to farm, adding that he also enjoys doing household chores.

“Opportunities like this are important to us and most especially to Ging-ging. We want him to be exposed to such training so we know what his skills are,” says Irene, Ging-ging’s sister.

Ging-ging is also proud that he is not a burden to their family. He knows he is helping their family through the earnings he gets from selling cleaning materials, and soon, from his work at Julyan’s Garden. “I am happy because I can help my mother to buy rice for us to eat,” he shares.

Going from supporting Julyan to supporting other people with disabilities on a sustained level has been a challenge for Rachel, but she is determined: “You just need to find your passion, something that motivates you to go on and do it all again.”

Her dream, she says, is to leave her son and her extended Zambawood family with a legacy that will always make them feel “loved, accepted, and empowered”.

Zambawood has also partnered with artists to create awareness of their trainees’ talents, and some of the paintings by Julyan and other trainees have been sold, with the proceeds going back to Zambawood and Julyan’s Garden’s advocacy work.

The more people interact with persons with disabilities, the more they will understand them, creating more opportunities for them, believes Rachel.

The closures may have set back the mission but Rachel has responded with innovative ways to keep the enterprise afloat: selling plants sourced from Bulacan, loam soil, fruits and vegetables from the north and recently, bringing sunflowers from Zambales to Manila. “You just need to do it, you cannot give up because no one else will do this for them,” says Rachel.

“The pandemic taught me that I can do more, I can love more and I can surpass more. It taught me that I am really blessed. I am grateful that I didn’t lose hope.”

Rachel Harrison Founder, Zambawood

Zambawood is a social enterprise. From relaxing at the resort, to visiting the farm and harvesting the produce, to enjoying a coffee at its cafe, you are supporting a platform that gives youth with disabilities a chance to grow their skills.

With the Philippines easing its travel restrictions, both resorts are ready to welcome tourists and employ and re-employ people with disabilities.

Its training programme is for youth aged 18 and above who have medical clearance to work, and the duration varies — a barista programme by government agency TESDA for example, is 178 hours. The trainees graduate with a licence that certifies that they are fit and trained to work. As of March 2022, Julyan’s Coffee Spot has rehired two of the trainees, while there are three trainees awaiting assignment at Julyan’s Garden. Rachel is in constant communication with TESDA and nearby schools for possible partnerships to train more youth.

Before the pandemic, corporate establishments such as GLOBE Telecom’s office in Makati opened their doors to Zambawood’s deaf trainees, who ran pop-up coffee kiosks on their premises. Zambawood hopes to see more corporate partnerships return as the pandemic eases.

I want to go to Zambawood

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases remain a concern, and various travel restrictions and safety measures remain in place across countries. During this time, we encourage you to respect prevailing rules and precautionary measures while travelling, and seek out experiences that support communities hit hard by the pandemic.

Shantanu is the director and project head of Habre's Nest, a wildlife travel enterprise on a mission to protect the red panda.

“I’ve had four years of experience in this region before we set up Habre’s Nest here in Kaiakata. Under the parent organisation Forest Dwellers, Habre’s Nest was our first project which is also rooted in sustainable tourism around rare species. While the red panda is our flagship animal, our intention is to protect the entire habitat. We undertake work where work is required but not enough is being done.

We decided to base our interventions here in Singalila because the belt extending from Nepal to the Indian states of Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh onwards to Bhutan, Myanmar, and China, is the best remaining habitat for red pandas in the wild. Singalila can be considered the epicentre of red panda distribution and could play a vital role in enabling the fragments to connect.

We chose Kaiakata even though the weather can be harsh at times because the views are unobstructed and it is surrounded by greenery on the Nepal and Indian side of the border which increases the probability of sighting the red panda.

We've captured more than 4,000 photographs of wild red pandas over a period of four years through tourism and achieved 98 per cent sighting of the red panda for our guests since 2016.

Our goal is to assign this area the status of a red panda reserve, which would aid with conservation while continuing to track and document red pandas and hosting tourists who might be inspired to do something on their own. We want to continue working with government authorities towards improved regulation within and around the national park to minimise and eventually, eliminate the harm being caused by unregulated tourism.”

Read more about Habre's Nest here.

When COVID-19 put a halt to the stream of travellers who visit the far eastern Himalayas hoping to spot a red panda in the wild, one would imagine a blissful reprieve for the shy creatures.

“Actually, during the pandemic, poaching actually increased,” corrects photographer and conservationist Shantanu Prasad. “We can’t stop it all. We call the authorities. But they have weapons. We don’t.”

Each day, Shantanu and his team of rangers at Habre’s Nest patrol the Singalila Ridge, which straddles Nepal and India. Covering anything from 10 to 20km on foot each day, they watch out for poachers and record any sightings of red pandas, to contribute to research on these elusive animals.

But Habre’s Nest is more than just a beacon of community conservation — it is also a source of livelihoods, ensuring that some of the tourism dollars in this region benefit the local community. The rangers are also employed as hosts and guides to travellers, so that they can explore the region while minimising harm to the environment.

With travel back on the radar, Habre’s Nest hopes to see visitors again and channel funds back towards protecting the environment.

Though daily sightings are currently reported by the Habre’s Nest team, this writer did not spot one during my three-day visit in 2019 (visitors are advised to stay a week to allow for higher chances of a sighting).

But while my expectations were high, surprisingly, I was not crushed by not seeing one. Instead, I went home enlightened by what I learnt about the tireless rangers, and thrilled by the stunning surroundings of the Singalila Ridge, which is more than just second fiddle to its famous russet-furred resident.

Stretching from central Nepal to northwest Yunnan in China, the Eastern Himalayas thread through Sikkim (India), Bhutan, the Tibetan plateau and northern Myanmar along the way. Ardent trekkers come to Singalila Ridge to complete the 50km trek from the town of Maneybhanjang to Phalut, the second-highest peak in West Bengal, India (3,595m). Others make for Sandakphu, the highest peak at 3,636m.

But for less rugged travellers, the route is also renowned as a vantage point to take in four of the world’s five highest peaks: Everest (8,848m), Kangchenjunga (8,586m), Lhotse (8,516m) and Makalu (8,485m).

An Indo-Nepali project, Habre’s Nest’s focus is on the wildlife that call the Eastern Himalayas home — protecting them and encouraging local communities to take up the mantle of conservation.

“Tourists aren’t always aware or sensitive about the forested areas they trek through and the wildlife that abounds within,” shares Shantanu, Habre’s Nest’s director

From trails being too crowded, to hikers making too much noise and leaving trash behind in the forest, “unregulated tourism”, as Shantanu puts it, is one of the biggest challenges faced by Habre’s Nest.

Habre’s Nest, which derives its name from the Nepali word for red panda, was formed by Shantanu after he learnt about the species’ endangered status.

Globally, less than 10,000 remain in the wild, living in the trees in mountainous regions. In the area earmarked for conservation by Habre’s Nest, there are just 32. An estimated 86 per cent of red panda cubs die within a year of being born; human activity is the main threat to the species.

In Singalila, the red panda’s main threats are feral dogs which may carry rabies and other diseases, and the clearing of forested land for wood and agriculture.

After identifying feral dogs as a key threat to red pandas, Habre’s Nest began holding vaccination drives for dogs with the help of animal welfare organisations, targeting dogs that belong to households as well as strays from nearby towns that follow trekkers around.

As they got to know the local community better, they realised there was a lack of medical facilities in the area. So they set up free medical camps, fostering greater trust.

This was followed by outreach sessions to create awareness of the need to protect the environment. Villagers were invited to attend training to monitor wildlife and record sightings in a 100sqkm area. Those working in the tourism sector were offered training to become more sensitive to wildlife.

When it ventured into wildlife tourism, Habre’s Nest made sure to hire only locally, ensuring that benefits from tourism stay local. “While the red panda is our flagship animal, our intention is to protect the Eastern Himalayas,” says Shantanu, who was a photographer before he became a conservationist.

Preserving the unique environment and wildlife of the area would in turn benefit locals in the long run as sustainable tourism also sustains livelihood opportunities.

Catching sight of wildlife is a game of chance; after all, truly wild creatures do not show up on demand to delight travellers.

Habre’s Nest recommends staying at least seven nights for higher chances of a sighting. This includes factoring in the altitude’s unpredictable weather and a day of travel to Kaiakata, which is on the Nepal side of the ridge.

Guests do not take part in tracking red pandas; a walk to see the red pandas is only arranged when rangers spot one on patrols. Each visit lasts no more than 15 minutes.

In the meantime, guests can also spend their time at the bird hide on the premises. I was able to effortlessly pass a few hours here — clicking a few photographs every now and then of the avian company, so I could learn their names later from the in-house naturalist.

For hikers, short trek options to Kalipokhri, known for its lake with dark waters, and to Tumling, a renowned viewpoint of both Kanchenjunga and Everest, are options.

The Habre’s Nest team includes ex-poachers who now work as rangers, and double up as guides for guests, as well as manage the kitchen and homestays. Mohan Thami, a ranger at Habre’s Nest, shares, “Before, the means for livelihood were threadbare so people would set traps and poach. Today there’s awareness and a change in behaviour.”

“As trackers, we do our bit to sensitise villagers. After all, it’s because of the red panda and the training that Kaiakata has gotten visibility and sees tourists from all over the globe.”

Mohan Thami Ranger, Habre's Nest

Currently there are 11 full-time and nine part-time staff. Habre’s Nest’s lodge comprises four rooms, which can house a total of eight to 10 guests. Twenty per cent of the profits are directed towards its conservation efforts, such as local outreach on forest protection.

Shantanu notes that a comprehensive census for red pandas is currently underway, with photograph-based evidence being shared with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

“Our goal is to assign this area the status of a red panda reserve – which would aid with conservation while continuing to track and document red pandas while hosting tourists who might be inspired to do something to protect the red pandas,” he shares.

“We want to continue working with government authorities towards improved regulation within and around the national park to minimise and eventually eliminate the harm being caused by unregulated tourism.”

A visit to Habre’s Nest empowers the local community to protect the environment and the species, while uplifting local livelihoods.

In addition to hiring locals as patrol rangers and in hospitality roles, Habre’s Nest dedicates 20 per cent of its profits to its non-profit arm, the Wildlife Awareness Trust for Empowerment and Research (W.A.T.E.R.)

Even when COVID-19 hit the tourism industry hard, Habre’s Nest continued to employ its rangers to patrol the forests for poachers.Read more about Shantanu of Habre's Nest here.Read more about Mohan of Habre's Nest here.

I want to visit Habre's Nest

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways you can support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

Mohan is a tracker at Habre's Nest, a wildlife travel enterprise on a mission to protect the red panda.

“I am from Maneybhanjang and have been associated with Shantanu and Habre’s Nest from the beginning. I’ve been a part of this initiative from when we were building this homestay ground up in 2016. Today, as a tracker who supports conservation, I earn enough to support my family.

Before, I didn’t understand anything or know enough about the red panda, even though I, like many others, would see them. Now, I understand the need for conservation and the value it adds to the biodiversity here. I understand better some of the behaviour of the red panda from having been able to observe it in its natural habitat.

Until a few years ago, the means for livelihood within and around these villages here were threadbare so some people would set traps and poach red pandas to sell the fur on the black market or sell the animal itself as a pet.

Today things are a lot different. There are laws prohibiting and penalising poaching. But there’s awareness and a change in behaviour too. Employment opportunities exist, thanks to the booming tourism.

As trackers, we do our bit to sensitise villagers every day. After all, it’s because of the red panda and these sensitisation trainings that Kaiakata has gotten visibility on the map and sees tourists from all over the globe.

Quite naturally, it has also brought competition and envy from peers within the tourism sector here. There have been instances when rumours are spread and Habre’s Nest gets wrongly accused, including that we keep red pandas inside the property. which is obviously ridiculous. Some things will need more time to change, I guess.”

Read about Habre's Nest here.

Photo courtesy of Shantanu Prasad

On an ordinary day, Phare The Cambodian Circus’ big tent is filled with the excited cries of guests as they watch Phare’s artists perform gravity-defying feats, the rising music of the live band, the colourful lights that catch the graceful moves of the dancers. All in celebration of Cambodia’s rich artistic history, presented through a contemporary lens.

But 2020 is no ordinary year, and Phare’s big tent has stood silent for much of the past nine months. plunging its staff and artists’ livelihoods into deep disarray.

No thanks to COVID-19, international travel had ground to a halt. The town of Siem Reap, usually bursting with over 2.5 million tourists a year flocking to the famed Angkor temples, is eerily empty, with boarded-up shop fronts and empty hotels.

“The atmosphere is devastating, a lot of people lost their livelihoods. Drivers, guides, hotels. No jobs. We don’t see the end in sight.”

Dara Hout CEO, Phare Circus

Phare circus, previously featured on Our Better World, is no ordinary circus. It is a social enterprise under Phare Ponleu Selpak, based in Battambang that has made art one of its pillars of improving life for the underprivileged.

The circus’s acclaimed performances, which tell stories of Cambodian social issues and history through theatre, music, dance and modern circus arts, have drawn over 100,000 spectators over the years, helping to sustain Phare Ponleu Selpak’s non-profit work. With performances halted, its reserves are stretched and its capacity to keep offering free education and training to Cambodian children and youth is under threat.

Kitty Choup, a Phare artist, had performed nearly daily, specialising in contortions, jumps and other aerial performances. This ended abruptly in March 2020, when the Cambodian government ordered public performances to close, to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Although she is still paid a basic salary, the income from performing stopped. To make ends meet, Kitty sells clothes online and makes fruit and vegetable juices at home to sell in a makeshift stand on her street. She continues to rehearse and train at home with her husband (also a Phare artist), in order to stay in shape and ready for Phare re-opening.

In August 2020, Phare was permitted to reopen for performances in a limited capacity on weekends. This was welcome news, but the situation remained perilous amid a near shutdown of international travel into Cambodia, as most of Phare’s usual audience were foreign tourists or travellers from Phnom Penh.

Undeterred, Phare decided to tweak their model. Previously, its steady revenue from tourism allowed it to offer free 100 tickets daily for Cambodians during its low season from April to October. Amid COVID-19, it is unable to offer free tickets, but it lowered ticket prices, and called for supporters — no matter where they were — to donate US$10 to sponsor a Cambodian family to watch a performance.

“Cambodia as a nation has lost the culture of going to live theatre and patronage, we are trying to revive the culture of going to live performances,” says Dara.

Complemented by street art displays and street food stalls, the revived programme was a hit. Though the audience size was a fraction of what it was before COVID-19 (about 70 to 100 nightly compared to 400), it still meant the artists were being paid for performances again.

More importantly, it was also a morale boost to see the big tent lit up once more. “We are a beacon of hope for our community. They see that we are open, not closed, during this time. And people will try and persevere,” says Dara.

The path to recovery is not without speed bumps. In November, amid a rise in COVID-19 cases, the government ordered Phare to halt performances once more. It was only allowed to resume performances on Jan 15, 2021 and the outlook remains uncertain.

Without performances to drive revenue, Dara says Phare will have to rely on its reserves built up over the years, and go into “sleep mode” in a few months and staff will only be paid a basic income. “We persevere, we try. We don’t want to lose our staff. We want to help everyone to survive, even on a pay cut,” says Dara.

Donations are welcome while Phare develops new revenue streams and brings in potential investors to help the non-profit cope in future, and hopes for travel to open up in 2021.

“We know Cambodia will be very reliant on tourists for a while,” says Dara. “I hope everyone who travels will take responsible travel seriously, and realise their money can impact the local community. There are grassroots, impactful organisations like Phare, and when you travel, you should do research and support these kinds of activities as tourists.”

And even amid the severe challenges, he hopes the stories of resilience in Cambodia travel far and wide. “People continue to have hope in their lives. When people plan their holidays to Siem Reap, I hope they support activities that bring hope to people.” Says Kitty, “I really love Phare, it is not just a business, it is a family. They have helped to keep us going, so that we can support ourselves and our family at this time.

“I just keep working, keep rehearsing, and keep thinking about the future performances. I know I will be performing again.”

Some members of Phare Ponleu Selpak are alumni of the Singapore International Foundation’s annual Arts for Good Fellowship, which fosters a community of practice that harnesses the power of arts and culture to create positive social change.

Phare The Cambodian Circus’ performances are not only original and deeply riveting to watch, they also support the social work of its parent non-profit Phare Ponleu Selpak and its education initiatives in Battambang.

Amid COVID-19, Phare has been allowed to hold performances in a limited capacity. You can sponsor a Cambodian family to catch a performance, and help Phare keep the lights on on its social mission. Check Phare’s website for latest updates on operations.

Any donation to Phare also helps bring the arts to underprivileged communities in Battambang, and develops livelihoods in theatre, graphic design and other visual arts. As the pandemic wears on, your donation can also help Phare continue to provide income and relief to its team and community.

Help Phare stay the course amid the pandemic

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways you can support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

Photo by Malika Virdi

“It’s not just about how much we can earn, but also about being able to share our dukh-sukh (sorrows-joys).” - Kamla Pandey, homestay host

As Kamla Pandey tells me this over a WhatsApp call, I could picture her in warm layers wrapped over her sari, as the winter sun bathed her house through its large glass window.

Just a couple of hours ago, the sun would have risen over the five snow-clad Panchachuli peaks, casting an otherworldly glow over the remote mountain village of Sarmoli. The village sits in Uttarakhand’s Munsiari district, close to the borders of Tibet and Nepal in the Greater Himalayan region, an 11-hour drive from the nearest airport and train station.

It was over many such mornings, way back in 2016, that I first got to know Kamla. Like many women in Sarmoli – and the neighbouring villages of Shankhdhura and Nanasem – she runs a homestay as part of Himalayan Ark, a community-owned social enterprise committed to responsible, purpose-driven travel in the region.

When COVID-19 decimated tourism incomes across the world, Himalayan Ark shifted its focus from tourism to digital upskilling, reviving traditional crafts and long-term food security.

As we chatted over the phone about the threat of the Omicron variant, Kamla confessed that yes, the pandemic came as a big jhatka (shock). But as a community that has been together through many storms over the years, they continue to sail together, no matter which way the winds blow.

Homestays seeded in conservation

Photo by Malika Virdi

Kamla didn’t always have the confidence — or the opportunity — to host strangers from around the world in her home.

In fact, back in 1992, when avid mountaineer Malika Virdi moved to Sarmoli, the only livelihood opportunities available to women were meagre earnings from agriculture, or demanding daily wage labour at construction sites.

About a decade later, when Malika was elected sarpanch (head) of the van panchayat — a 70-year-old village institution for the sustainable management of forests — she set out to change this, by connecting conservations and livelihoods.

“The use of the forest needed to be regulated, but why would anyone be interested in conserving something they were so desperately dependent on [for fuel and fodder]?” recalls Malika in a recent conversation over a video call.

The proposed alternative: a nature-based tourism initiative that became the foundation of Himalayan Ark. Himalayan Ark would assist members in accessing tourism-linked incomes, and they would commit to participating in local conservation work like planting, maintenance and safeguarding of the land.

The homes of Himalayan Ark’s members became a vehicle for empowerment when they started hosting travellers. Photo by E Theophilus

Back in 2004, only 13 out of 300 van panchayat rights holders signed up, including Kamla. “People were sceptical as to why someone would choose to stay in our village over the hotels in the bustling Munsiari bazaar,” Kamla had told me when we first met.

Global and domestic visitors however, quickly became drawn to Sarmoli, both as a base for high-altitude treks in the Kumaon Himalayas, as well as for volunteer tourism, student trips and slow travel.

By 2019, Himalayan Ark’s network had grown to 20 women-led homestays, managed by a roster system where priority is given to those who have no alternate source of income. Twenty-five guides had been intensively trained in birding, high-altitude trekking and natural history, of which over half are women. Having travelled extensively in India, that is a statistic I constantly marvel at, for Sarmoli is one of the only places in the country where I have hiked with a female high-altitude guide.

A community that celebrates its cultures

A feast for the eyes and the appetite on Ghee Tyohaar, an Uttarakhand festival. Photo by Trilok Singh Rana

What first drew me to Sarmoli though, was not its equitable tourism model but Himal Kalasutra, a mountain festival for the locals (not tourists, though they are welcome to join). People from villages across the Gori Valley come together to go bird watching, learn outdoor activities like yoga or ultimate frisbee, and get a sneak peek into digital tools like Wikipedia.

I joined a bird watching excursion amidst oak and deodar forests bursting with blooming red rhododendrons, participated in a yoga session in the surreal backdrop of snow and mist clad mountains, and cheered on locals as they set out on a high altitude marathon to Khaliya Top, a spectacular alpine meadow at an altitude of 3,500m (an altitude gain of 8,000 feet over 20km) — best hiked slowly by city folk like me.

Photo courtesy of Himalayan Ark

Inspired by the festivities, I offered an impromptu Instagram tutorial to young adults from Sarmoli and Shankhdhura – which led to the creation of @voicesofmunsiari, India’s first Instagram channel to be run entirely by a rural village community. In 2017, with smartphones crowdsourced via my blog, an Instagram and photography workshop became part of the official festival line-up.

Later, I learnt that in true spirit of community ownership, Himalayan Ark’s homestay hosts keep 80 per cent of the revenue, and voluntarily contribute 5 per cent towards community development — 2 per cent goes to the van panchayat, while 3 per cent goes to a fund that offers interest-free loans for community members to upgrade their homestays.

Over the years, guests have also volunteered their skills to help Himalayan Ark grow, sharing their knowledge in mapping local geography, environmental issues, women’s rights and rural tourism development. “They get an insider's view of community life in the Himalayan mountains and also end up making lifelong friends,” shares Malika.

A return to tradition, an eye on the future

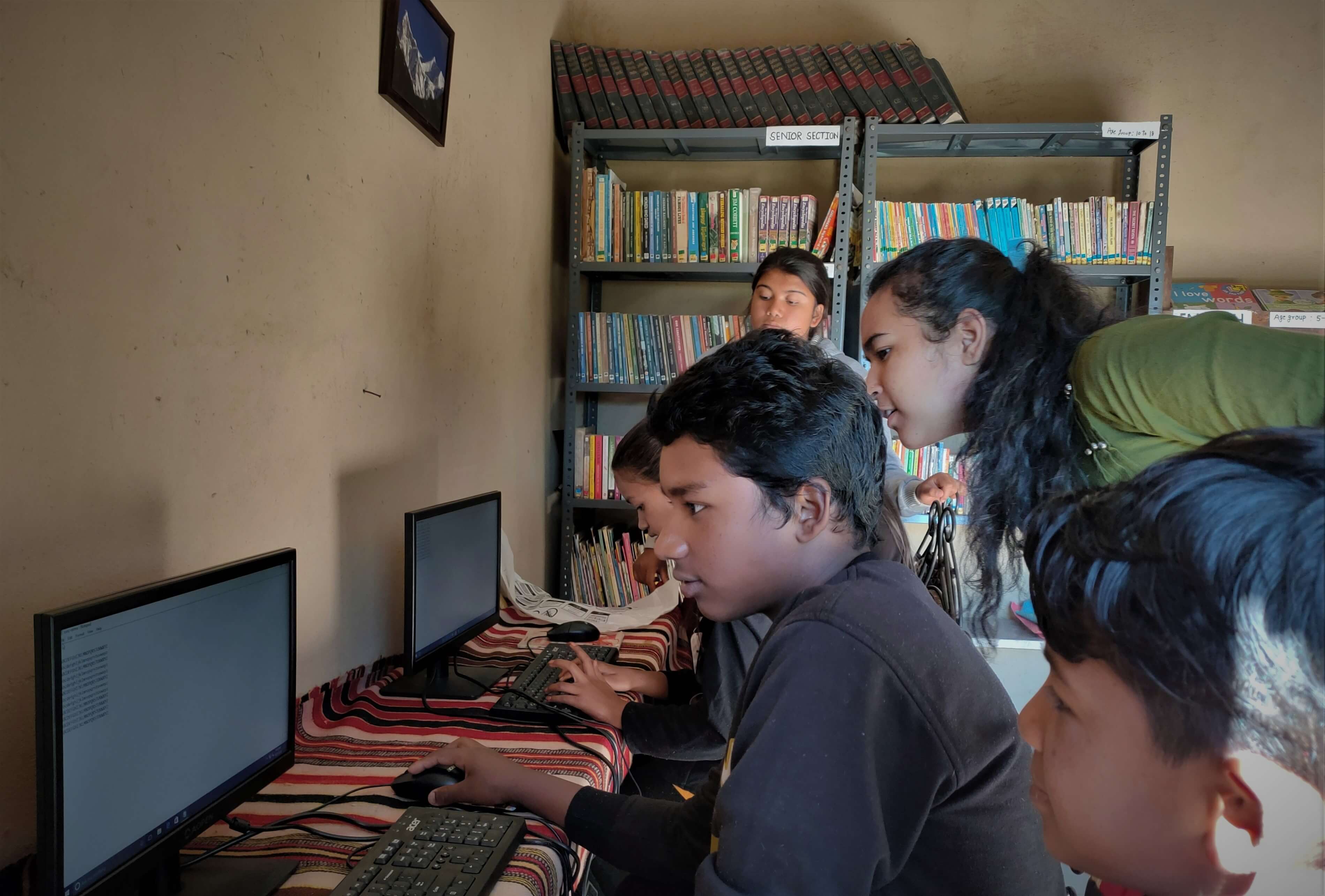

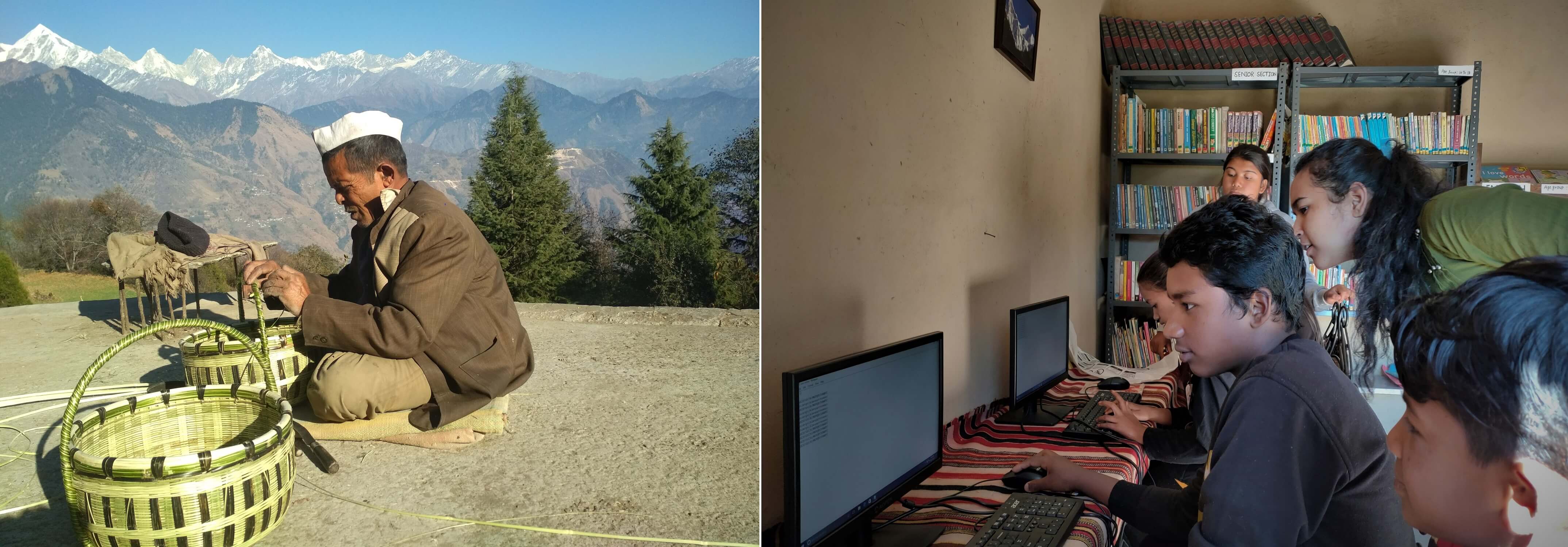

[From left to right] Master craftsman Nain Ram demonstrates how to weave bamboo; Children keep up with school in the digital resource centre opened by Himalayan Ark. Photos by Trilok Singh Rana (left) and Kaushalya Arya

COVID-19 spared the remote mountain villages of Munsiari the worst of the pandemic, but took away their primary source of livelihoods.

“Tourism was all about sharing our rural lifestyle with travellers,” says Malika. “The pandemic left us with no tourism, but we still had our rural lifestyle.”

After the initial shock, Himal Prakriti, the non-profit arm of Himalayan Ark, quickly pivoted into developing alternate sources of income for the community, powered by CSR funding and individual donations.

With a renewed focus on agriculture and food security, some homestay owners and guides were trained and paid to build hoop houses — small, predator-proof greenhouses made with locally available galvanised iron pipes. “We’ve set up vegetable and forest nurseries, and distributed seeds like capsicum, cucumber, fenugreek and broccoli,” Kamla tells me excitedly.

Villagers building hoop houses to increase food security. Photo by Kamla Pandey

So far, Himal Prakriti has been able to reach 100 to 150 economically-depressed farmers across the Gori Valley, many of whom are women.

It then shifted gears towards reviving crafts lost to time, starting with a workshop on likhai – intricate hand-carving on walnut wood, a skill once possessed only by the men of the Ohri community. Until a few decades ago, homes across Kumaon were fitted with likhai-adorned doors and windows, but as demand for traditional houses fell, many artisans gave up their craft.

By the end of the workshop, participants were able to retrofit their homestays with self-carved mirror and window frames.

Abandoned homes with likhai frames (left). Villagers in Munsiari tried their hand at reviving the craft by learning from artisans. Photos by E Theophilus (left) and Malika Virdi

Similarly, members of the community spent time relearning the backstrap loom – a simple concoction made with ropes, sticks and a strap, worn around the waist – once central to the Bhotiya people as they roamed the mountains with their herds.

Reviving these crafts not only created a sense of ownership, community and pride, it also enabled the members to create products for sale through the @voicesofmunsiari Instagram channel.

The focus on rural life did not neglect the need to stay connected to urban demands. As schools shut and lessons moved online, Himalayan Ark decided to convert a planned café space into a digital resource centre. Children who did not have access to smartphones or laptops were still able to attend online classes and study in a socially-distanced setting.

Gearing up for the “new normal”

Photo by Malika Virdi

The pandemic exposed a gaping urban-rural digital divide — and with the interest in travel returning, bridging it remains crucial, so that the Himalayan Ark community can grow their business.

Over the past five years, Himalayan Ark community members, despite not having the social media savvy of more privileged peers, have been sharing glimpses of their lives through @voicesofmunsiari.

Encouraged by their pursuit, Malika and I, together with Osama Manzar of the Digital Empowerment Foundation, co-founded Voices of Rural India — a curated platform for homestay hosts, guides and other community members, to share their stories in their own voices, while building digital storytelling skills and earning an income through digital publishing. One of the first stories published was written by Kamla.

When Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee, an elite Indian university, broached the idea of documenting traditional crafts in the region, two women from the community led the multimedia documentation. Among them was Bina Nitwal from a Bhotiya family, who, armed with her smartphone, interviewed her elders across the valley about the history of the backstrap loom that she herself is re-learning to use.

Mohini demonstrates how to use a backstrap loom to weave textiles. Photo by Bina Nitwal

In the new “normal,” we have no idea what the pandemic (and climate change) might throw at us. But one thing is for sure: the community in Munsiari, held together by Himalayan Ark, will continue to sail towards new horizons.

“Our goal has always been to forge a deep rishta (relationship), both within the community, and of the community with the landscape,” Malika told me. In the face of market forces and looming uncertainties, it’ll be more important than ever.

When you book a sojourn at Himalayan Ark homestay, or trek with one of their guides, you support a community in its efforts to protect the environment, as well as maintain a sustainable way of life.

Himalayan Ark’s homestay hosts keep 80 per cent of the revenue, and voluntarily contribute 5 per cent towards community development — 2 per cent goes to the van panchayat, while 3 per cent goes to a fund that offers interest-free loans for community members to upgrade their homestays. In 2019, tourism brought in over 50 lakhs (US$75,000) to the community.

If travel is not an option, you can also support Himalayan Ark by purchasing their crafts through their community-run Instagram page, @voicesofmunsiari.

I want to support Himalayan Ark

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways you can support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.

Bina is a member of Himalayan Ark, a community-owned social enterprise that supports villagers to run homestays while giving back to their communities.

"As a homestay owner with Himalayan Ark, tourism has been my main source of income since 2010. During the pandemic, we suddenly found ourselves with no income but a lot of time on our hands. This was an opportune time to revive the craft of weaving with the forgotten backstrap loom.

Till some 50 years ago, when trade flourished between our Johar Valley and Tibet, my Bhotiya forefathers and their families led a transhumant lifestyle — we would travel in caravans with their sheep herds, traversing a fixed migration route that stretched from the trade posts in Tibet, through Johar valley in summer and down to the plains of north India in winter. At each padav (campsite), the women set up their handy pitthi – backstrap looms – and wove with the wool gathered from their sheep.

But in 1962, the Sino-Indian war put an abrupt end to the trade and with it, to our lifestyle. Our families settled in villages and began weaving on the more conventional looms. Over the years, the craft of the backstrap loom began to fade, living only in the memories of older women.

It was the karbachh — woolen saddlebags that were strapped onto sheep to carry trade goods like salt and dry rations — that first caught our attention. Woven on a backstrap loom, its classic design and weave ensured that it was durable and weather-proof. Could we relearn the craft, and adapt it to our settled lives?

To our dismay, we could locate only a couple of backstrap looms in the village. People had either lost them, burnt them as firewood, or used its main shaft as a bat to play cricket. It was also challenging to find someone to train us. We learnt that there were still some skilled women in Paton, a village across the valley. The young weaver who came to teach us though, had to first ask Nomi Datal, a 92-year-old weaver, for a quick tutorial, despite her poor eyesight.

We spent the quiet months of the lockdown learning to cast the warp on pegs driven into the ground, and use this mobile loom to weave with the local coarse wool that nowadays is discarded by shepherds for want of a market.

I cherish the happy hours we spent weaving fabric for upholstering chairs, and making bags and belts – and felt a quiet sense of triumph in keeping this craft from slipping through the fingers of time.

Although we no longer weave our own clothes, our craft lives on. Travellers who come to stay with us can buy items made from local wool, often dyed with local plants, with motifs and designs inspired by nature.

We’ll be thrilled to share with them the craft of weaving on our traditional looms, so when they go back to their worlds, they’d have experienced a touch of the magic that comes with creating our own cloth."

Read more about Himalayan Ark here

Meet Trilok of Himalayan Ark here

People doing good. Causes you can support. Subscribe for a weekly dose of inspiration.

Our Better World is the digital storytelling initiative of the Singapore International Foundation, which brings world communities together to do good.

Our Better World is the digital storytelling initiative of the Singapore International Foundation, which brings world communities together to do good.