Travel in a pandemic - through your taste buds

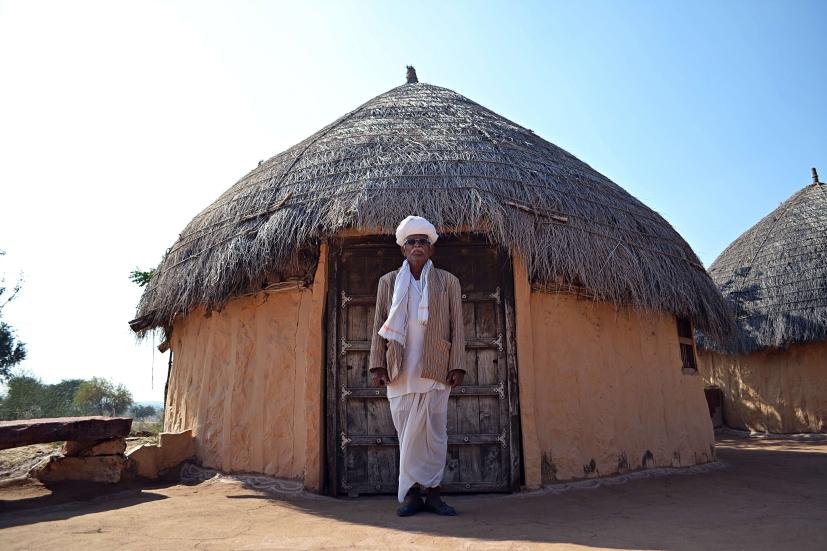

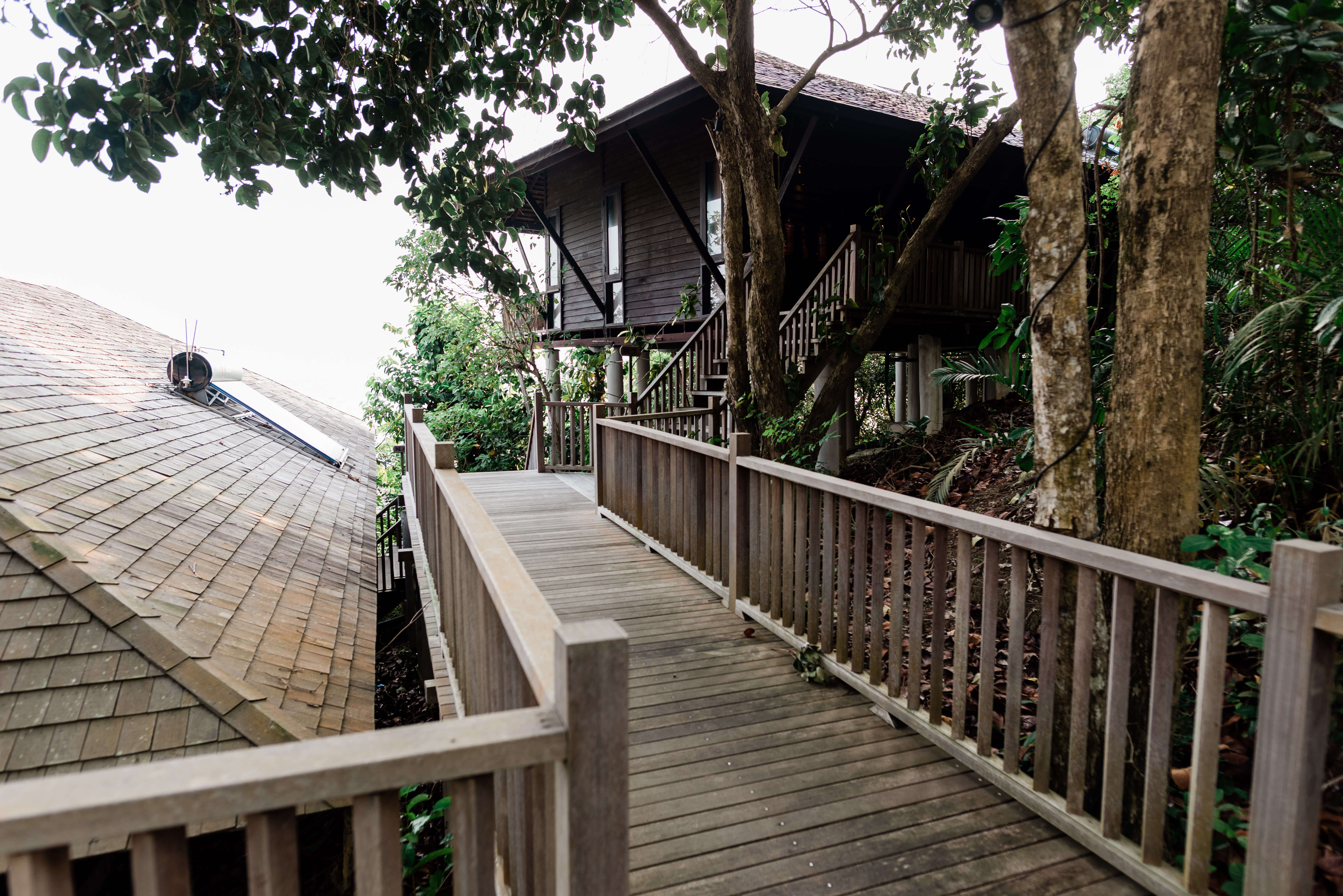

Two years ago, I spent a few days with members of the Akha tribe in the hills of northern Thailand, vegetable-picking in the jungles, enjoying a traditional meal in bamboo over open fire, and learning about their culture and traditions. Organised by social enterprise Local Alike, it introduced me to the concept of sustainable, community-based tourism aimed at empowering indigenous peoples.

Unfortunately, tourism came to a sudden halt during the COVID-19 outbreak. Many of Local Alike’s community partners saw their tourism revenue plunge — by about 10 million baht (approximately US$300,000) — with little recourse to alternative income sources. This put the very concept of sustainability to the test.

The solution? Bringing a taste of the hill tribes to city doorsteps, through a new food delivery service.

Culture at your doorstep

Local Aroi, which was set up by Local Alike to offer food experiences (aroi means “delicious” in Thai), launched Local Aroi D in Bangkok, a delivery service offering meals made from ingredients sourced from Local Alike’s hill tribe partners, to generate income for them.

The new initiative was a more than palatable solution, tapping on the tribes’ culinary strengths and the rising demand for food delivery due to people working from home amid a lockdown in Thailand. “Bringing food from the community to the platform, we built it for the reason that not every local community was successful in tourism,” adds Local Alike founder and CEO Somsak Boonkam.

Rawimon Mongkolthanapoom, who goes by Keaw, is Akha, from the Pha Mee region — one of the 15 communities who came onboard the initiative.

“There were no tourists and most shops were closed. So the community had to find an alternative way, and they distributed fruits such as lychees, oranges, and so on,” says Keaw. “We had to help farmers in our community to make income instead of relying solely on tourism. Local Aroi also supported our community by using our local ingredients to prepare their dishes.”

So far, about 1.8 million baht (US$57,000) has been directed back to the local communities, while community members have been hired for “chef’s table” experiences. Though the initiative ended in September, Local Alike plans to bring it back in future, while continuing to explore chef's table experiences.

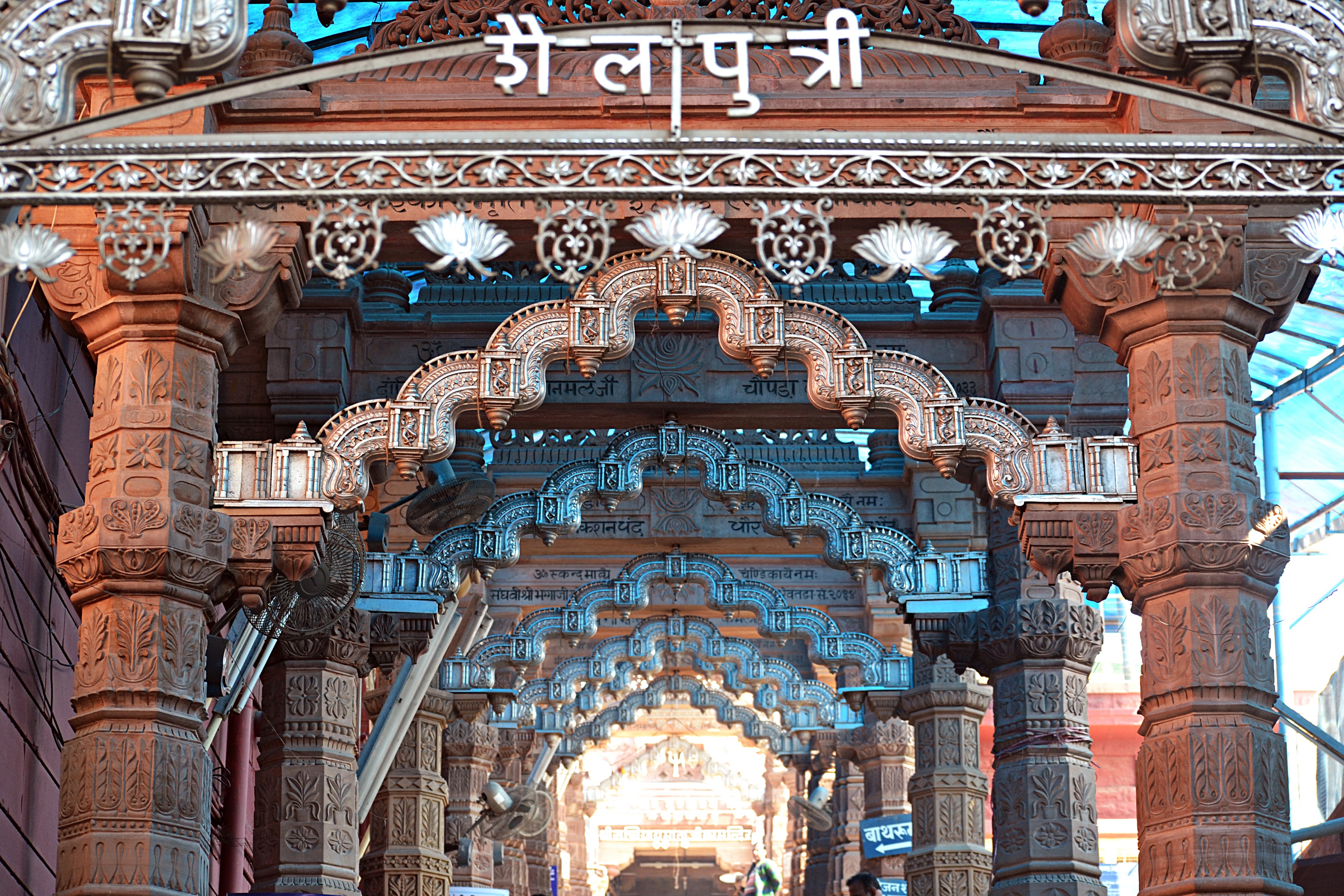

The initiatives are creating new awareness and appreciation of the tribes’ culinary traditions. Recipes handed down from generations like deep fried spring rolls Khlong Toei-style and kanom-tarn (or palm sugar cake) from Baan Pa Nong Khao, are given a fresh twist for events. Akha-style chilli paste, known as a palachong, is reinvented into a spaghetti dish [pictured below] available for delivery on Local Aroi D.

Building awareness for the long run

For Keaw, the experience is ultimately “more about culture-sharing and building awareness”. The hill tribes are proud of their abundant land and resources, and are eager to share it, she explains, but for years, they have had to bear with unwelcome notoriety from the region’s history as a trade route for opium.

Though culinary exchange, Keaw is keen to move on from these outworn tales and help visitors see her people through a fresh lens. Sharing that her favourite meal is ku chi lu — crispy pork belly stir-fried with rakshu root — Keaw explains that rakshu is a local herb in the Akha kitchen that enhances taste. Although all parts of the plant are edible, the root is the most popular because of its crispy texture when cooked, and it is said to have anti-cold properties and helps reduce cholesterol.

![Keaw getting ready to showcase the culinary gems of the Akha tribe [left]. She hopes that interest in northern Thailand cuisine creates more interest in the country’s indigenous cultures. Photo from Local Alike](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Webp.net-compress-image_0.jpg)

The effects of COVID-19 have been dire, but it has also piqued the interest of Thais in the diversity of the culture within the country beyond their own. Through platforms like Facebook Live and Zoom, it has organised well-received virtual village tours in Thai, such as “From Local Chefs to Local Aroi” with Baan Luang Neau in Chiang Mai and Baan Khok Mueang in Buriram. Another virtual event, “A Mother Teaches Her Sons to Cook”, brings a new breed of audience-diners along on gastronomical adventures while sourcing local ingredients and re-creating recipes.

With the Thai government encouraging domestic tourism, the hope is that the interest in hill tribe cuisine will eventually lead people to visit the region in person. “We brought local food to people in the central region who haven’t yet had the opportunity to visit Pha Mee. We present these fabulous experiences from special dishes using authentic community ingredients. When tourists finally visit Pha Mee, they are familiar that this is its local dish,” says Keaw.

Somsak holds a warm hope for this relationship with the indigenous communities to continue and to see the Local Aroi brand evolve into one that brings local traditions to the global stage. “It should be the centre of the community's signature recipes,” he says. “I will do my part in bringing these conversations to the dinner table - till the flight paths open up and I get the opportunity to recapture the flavours of Thailand’s hill tribes.”

Local Alike was one of the winners of Singapore International Foundation’s Young Social Entrepreneurs programme in 2014. Through mentorships, study visits, and opportunities to pitch for funding, the programme nurtures social entrepreneurs of different nationalities, to drive positive change for the world.

If you live in Bangkok, consider ordering a meal from Local Aroi D, and look out for pop-up dining experiences featuring menus inspired by hill tribe cuisines. Your order will support the tribes supplying the ingredients for these meals, the chefs hired from local communities to prepare these meals, as well as promote more awareness of the respective tribes’ cultures.

When travel resumes, consider booking a trip with Local Alike. By exploring communities like Suan Pa and Pha Mee through Local Alike, you help to support responsible tourism led by the local community members, and fuel sustainable livelihoods. It also helps to foster cultural exchange and encourage the preservation of traditions. As of 2019, Local Alike has worked with 100 villages in 42 provinces and created over 2,000 part-time jobs.

Read about our trip in 2018 for more inspiration.

Help Local Alike stay the course amid the pandemic

At the time of publishing this story, COVID-19 cases globally continue to rise, and international travel — even domestic travel in some cases — has been restricted for public health reasons. During this time, consider exploring the world differently: discover new ways to support communities in your favourite destinations, and bookmark them for future trips when borders reopen.