No time to read? Here’s a 30sec read

No time to read? Here’s a 30sec read

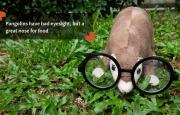

In an enclosure at Save Vietnam’s Wildlife’s (SVW) rescue centre, a resident pangolin’s snout appears at the entrance, followed by her bulbous body and tail covered in an armour of scales. These strange, enigmatic animals have been referred to as the “modern-day dinosaur”, having survived for 80 million years. But they're also at risk of going the same way - extinction. Prized for their supposed medicinal value, they are being hunted and eaten at an alarming scale. Enter SVW, which is on a mission to educate the public about the pangolin trade, while rescuing poached pangolins, rehabilitating them, and releasing them into the wild.

A note from OBW: Since publishing this story in March, and with the spread of COVID-19 across the world, several theories have emerged as to the origin of the novel coronavirus and how it first entered the human population. A popular postulation among scientists is that it had jumped species from a bat to a secondary animal (such as civets and pangolins) and finally to humans. Central to this idea is that the illegal wildlife trade is widely thought to be a key component to the spread of deadly pathogens, such as COVID-19.

With the pandemic shining a brighter spotlight on countries long recognised as having a rampant illegal trade in wildlife, governments have been pressured into taking significant steps to end it.

Vietnam, where our story subject Saving Vietnam’s Wildlife is based, announced on 24th July 2020, that it has banned the import of wildlife and wildlife products to reduce the risk of new pandemics. This move, which also bans the sale of such items online and in wildlife markets, was welcomed by conservationists.

In an enclosure at Save Vietnam’s Wildlife’s rescue centre in Cuc Phuong National Park, a resident pangolin’s tapered snout appears at the entrance to her darkened boudoir. Nostrils held high, she sniffs the air vigorously, her small, jet black eyes survey the surroundings.

Before long, her timid hesitance is overtaken by curiosity and she emerges. From behind her inquisitive face, a bulbous body and tail waddles past, covered in a shimmering armour of brownish, “click-clacking” scales.

Nothing quite prepares you for the first time seeing a pangolin - at once clumsy, majestic, otherworldly.

These strange, enigmatic animals have been referred to as the “modern-day dinosaur”, having survived for 80 million years. But at the rate they are being poached and slaughtered for commercial gain, they might just go the same way - extinction.

Night wanderers

Being nocturnal, it is unusual to see this shy, solitary Sunda pangolin out and about during the day.

Save Vietnam’s Wildlife (SVW) Keeper, Dinh Van Tham, explains that it might be because this mother pangolin was recently moved into the semi-wild enclosure with her slumbering son ‘Ha’. He says she is probably a little stressed, and might be eager to map out her surroundings using her powerful sense of smell.

At 61 years old, Tham is the oldest keeper at SVW’s centre, a three-hour drive from Hanoi, Vietnam. He is also SVW’s longest-serving caretaker, and has grown to love these gentle, prehistoric-looking creatures.

“I used to think animals are just animals,” admits Tham. “[But] caring for animals for a long time makes them my beloved friends. I love them more and more.”

He adds, “My awareness about the natural environment has [also] improved, as I have learned a lot from Save Vietnam’s Wildlife training programmes and the people around me.”

“Because pangolins are increasingly endangered,” he warns, “if we do not rescue and preserve them… part of our natural ecosystem will disappear.”

Besides, the species also plays an important role as natural pest controllers, maintaining the populations of their prey in forests, primarily ants and termites. While at the same time improving the quality of the soil, as they dig and forage for food.

Most trafficked mammal

Pangolins are said to be the world’s most trafficked mammals on the wildlife black market. Between 2000 and 2019, conservation NGO TRAFFIC estimates that nearly 1 million pangolins have been traded illegally at a global level.

Photo: Save Vietnam's Wildife

As the only living mammal known to be covered with a layer of true scales, they are prized for their supposed medicinal value.

Consumers of traditional Chinese medicine in China and Vietnam believe a pangolin’s scales can cure anything from arthritis to cancer to infertility. Made from keratin, a protein that forms fingernails, hair, hooves and claws, there is no scientific evidence yet on the efficacy of scales as a treatment.

But it’s not just their scales that are in demand, which per kg can cost between US$700 to US$1,000.

According to SVW Founder Nguyen Van Thai, restaurants charge between US$500 and US$600 for 1kg of pangolin meat, which is served as a delicacy to a rising middle-class, looking for ever more exotic wildlife dishes to impress guests.

Photo: Save Vietnam's Wildife

"The practice of consuming pangolins and pangolin scales has existed as part of Vietnamese culture for a long time, but it wasn’t serious,” says Thai.

With the prevalence of social media, more people have become aware of pangolins. As their curiosity increased, the demand for this otherwise little-known animal grew too.

Laments Thai, “Many people see them [pangolins] as something lucky and special… People selfishly consume pangolins to show off their class, since pangolin products are rare.”

Trifecta of origin, transit and destination

Vietnam is not only a source of endangered pangolins. The country is also a transit and destination hub for the illicit trade in them.

Last April, Singapore authorities uncovered a world record haul of pangolin scales originating from Africa and bound for Vietnam. It was worth S$52 million (US$37.2 million). Some 17,000 pangolins were believed to have been killed to produce the 12.9 tonnes of scales. Less than a week later, another 12.7 tonnes of scales were seized. Its intended final destination? Vietnam.

Photo: TRAFFIC

In demand and in danger of extinction

The IUCN classified all eight pangolin species threatened with extinction in 2014, and subjected them to a global commercial trade ban. In Asia, the Sunda, Chinese and Philippine species have been listed as Critically Endangered, and the Indian pangolin as Endangered.

“When I was seven or eight years old, I saw the Chinese pangolins with my own eyes,” recalls Thai. “But within 10 to 15 years, they have vanished. Now you don’t see them in Vietnam [in the wild].”

Witnessing these “benign and extraordinary animals” disappear from the forests in his backyard motivated Thai to become a ranger and “commit to protecting this animal from extinction.”

After graduating from university, Thai worked at Cuc Phuong National Park with the Carnivore and Pangolin Conservation Program for more than a decade, eventually becoming its head keeper.

Formally government-run, the programme is now managed by Save Vietnam’s Wildlife, which Thai set up in 2014.

While SVW takes in other wildlife like civets and otters, their primary focus is on pangolin conservation, rehabilitation and release. To date, SVW has rescued 1,600 pangolins and returned 1,000 to the wild.

Despite the successes, wildlife conservation has exacted an emotional toll on Thai and his team.

“During 15 years working with pangolins, I still feel a sense of sadness when we haven’t been able to solve problems, like poaching, trading or consuming pangolins,” he says with a tinge of regret.

“One of the really sad moments was when I went to rescue 100 pangolins. On that day, up to 80 pangolins died, and only 20 of them survived,” recounts Thai.

“After putting all the effort into rescuing them, our team, including myself, felt hopeless in front of the deaths,” he adds. “I have never experienced sadness like I did that day.”

Tham, himself a sensitive soul, is no stranger to disappointment over the years. He recognises that rescue and rehabilitation work can be as tough on humans, as on his pangolin friends.

“Unlike humans, animals aren’t able to tell us when they have problems. It’s not simple for us to know their condition,” Tham says. “Even though we tried hard, we were unable to make them better. We feel very sad about the limitation of our ability [to save them].”

Tough creatures to keep alive in captivity

Furthermore, pangolins are notoriously difficult to care for in captivity, as they have a unique diet of termites and ants.

“The second reason,” says Thai, “is that pangolins are from the wild, so it is tough to make a functional living space that mimics their natural habitat.”

It is to SVW’s credit that they have managed to achieve reputed survival rates in the world of pangolin conservation - more than 60 per cent of rescued wildlife are successfully rehabilitated and released.

Still, Thai is optimistic about the future. SVW works closely with government agencies to ensure that laws are enforced, that there is cross-border cooperation due to the transnational nature of the crime, and that local police respond to and report faster on rescue operations.

“The law has an influential impact on the trading market,” Thai says. “The number of large quantities [of trafficked pangolins] has declined. Instead, they [traffickers] are transporting them in smaller quantities and through different avenues.”

Thai continues, “I strongly believe that we can protect and prevent pangolins from extinction, based on the efforts of people, especially the young, who are getting more involved in animal conservation.”

First of its kind anti-poaching unit in Vietnam

SVW’s work does not stop after the pangolins are released into the wild, where they remain vulnerable to being recaptured. An Anti-Poaching Unit (APU), the first of its kind in Vietnam, was formed to patrol and protect the forests at Pu Mat National Park against illegal wildlife hunters.

Says Thai, “When pangolins are being released, we installed transmitters onto the pangolins and fly drones to continue looking after them. They are doing very well.”

In the long-term, changing the mindsets of the community will be essential to ensuring that Vietnamese understand the value and importance of protecting pangolins.

SVW does this by showing how actions like poaching, trading and consumption harm not only their environment, but also Vietnam as a country, “on our economy and pride,” says Thai.

Community outreach sustains conservation

Building a future for pangolins has also meant recruiting locals to be part of SVW.

Thai explains, “First, they understand the problems and the issues of the area. Secondly, we can find other financial alternatives by providing them jobs so they won’t have to hunt and make a negative impact in the jungle.”

By changing the way locals think, Thai says the “forest is a much safer place for animals,” with fewer snares and a drop in hunting activities.

Former policeman Loc Van Thang is now part of SVW’s anti-poaching unit, going out on 10-day patrols that take him deep into the verdant reaches of Pu Mat National Park.

Thang says that people in the community would use pangolin scales and install traps and bring dogs to hunt for pangolins in the forests close to his home in Pu Mat.

Now this soft-spoken father-of-two says he can be part of efforts to protect Vietnam’s forests and wildlife, for the sake of future generations.

“She [elder daughter] loves to hear me telling stories of patrolling and living in the forest,” says Thang. “I tell her stories of the pangolins, where they live, how they grow.”

SVW also conducts workshops at schools, and Tham believes this builds awareness about the natural environment and its inhabitants.

“They love wild animals more and also want to protect and preserve them,” says Tham.

“I asked them whether they want to eat wild animals, they responded, ‘No eat, no kill,’ and if they saw anyone doing so would inform the authorities.”

SIGN THE PETITION

Tell Vietnam's Congress to ban wildlife consumption and trade, which besides protecting endangered species can help ensure public health and safety. Put your name to this important call for change here.

About Save Vietnam’s Wildlife

Save Vietnam’s Wildlife is a non-profit organisation based in Cuc Phuong National Park in Vietnam. It was founded in 2014 with the mission to save animals from illegal trade, protect wildlife strongholds and continue to monitor released individual and wildlife populations. Part of its conservation efforts involves advocacy work and education outreach to communities and schools.

Contributors

Director, Camera & Editor

Dixie Chan

Producer, Photography & Writer

Executive Producer

Please rotate your device to continue the slideshow

Creature Feature

Click on the animal icons to get to know our wildlife stars better!

Creature Feature

Tap on the animal icons to get to know our wildlife stars better!

Gallery

Lights! Camera! Action! Photos and 360 videos - starring our featured wildlife.