No time to read? Here’s a 30sec read

No time to read? Here’s a 30sec read

Clashes between humans and wildlife have been on the rise; with long-tailed macaques frequenting the spotlight. Non-profit charity organisation ACRES has been working behind the scenes to help fix the macaque’s bad reputation in hopes of helping Singaporeans understand their behaviours as well as their crucial role in creating balance in our ecosystem. Dedicated to nurturing a compassionate society towards wildlife, ACRES believes that all it takes is empowering individuals with the knowledge of what to do when one encounters wildlife, and understanding how wildlife is essential to our survival. This subtle mindset change can help Singapore achieve its ‘city in nature’ vision, where people and macaques can coexist and thrive alongside each other.

Ask anyone on the street about long-tailed macaques and you’ll be met with chuckles, grimaces or fear.

An ubiquitous sight in Singapore, especially on the invisible boundary where forest fringes meet the concrete jungle, macaques often venture onto sidewalks, car parks and nearby housing estates. Where they may then grab food from unsuspecting park visitors, scale great heights to enter houses, and rummage through trash bins and eat leftovers — just to name a few situations.

“Macaques have a bad reputation because of their urban behaviour. And also the lack of understanding of these animals,” says Joe Kam, wildlife management officer for the Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (ACRES).

When a macaque complaint surfaces, Joe is likely to be next on the scene. A former IT professional, Joe started as a volunteer at ACRES in 2017. While volunteering, Joe’s curiosity and passion for wildlife grew tremendously and he eventually traded in his job for a full-time role at ACRES, where responding to hotline calls from the public about animal encounters is part of his daily life.

He and his team spend much of their time in residential and commercial areas near forests and nature parks, helping members of the public who have no idea what to do when they encounter wildlife.

If there is a human-macaque conflict in an estate, his team is deployed to the site from 7am to 7pm daily to monitor the macaques, to attend to residents’ concerns and to distribute advisories. Sometimes these conflicts go on for months. He also engages park-goers who encounter macaques fleetingly.

Joe laughs when he recounts that he is often accused of being a ‘tree hugger’ and people naturally assume that he prioritises animals above humans.

“We are trying to help humans,” he shares. “Because by helping humans to understand the dos and don'ts, we are indirectly helping animals.”

Since ACRES started in 2001, its unwavering mission has been to champion and nurture a society that is compassionate towards wildlife. Besides running a 24-hour animal rescue centre, the charity also conducts outreach and educational programmes for the public.

Food conditioned animals

French fries. Chicken curry. Cake.

These are some of our favourite foods. And it is no surprise that macaques have gotten used to such foods as well.

“I've seen monkeys drinking milkshakes. I've seen monkeys eating McDonald's,” lists Joe, “I've seen monkeys eating chili padi.”

Once the first-ever food offering is made, a macaque won’t easily forget the experience.

“The fear of humans in the monkey will eventually slowly disappear,” says Joe. He adds that once this happens, macaques will equate humans as friendly and approach them more comfortably.

“Human food is so yummy. High sugar, high salt, high flavours, where they (macaques) can’t find in the forest. And they would love to have more,” says Joe.

Over the years, macaques have become more bold, often leaving the fringes and into urban settlements, increasing the contact with humans.

Attempts have been made to clamp down even more on errant wildlife feeders, well-intentioned or otherwise. In mid-2020, amendments were made to the Wild Animals and Birds Act, now renamed the Wildlife Act, to include stricter penalties for feeding of wildlife. Feeding wild animals islandwide is now illegal. Previously, it was only illegal in parks and nature reserves.

So far, the act has taken enforcement action against 62 people and more than 20 have been summoned to court.

Human-wildlife conflict

Clashes between macaques and humans go way back, close to the nations’ beginning.

The first recorded altercation happened at the Singapore Botanic Gardens in the 1960s, and subsequently this conflict fuelled the decision to begin the culling of these primates.

These primates have remained close to the urban environment, though not by their choice. Since 1819, Singapore has lost more than 95 per cent of its original forest cover, leaving two major forest reserves behind – Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and Central Catchment Nature Reserve. Surrounding these forests are numerous housing estates, increasing the proximity between human and macaques.

“The buffer between the forest and residential, commercial areas, it’s actually very small,” says Joe. “So from time to time, when they venture out, they will go into residential estates. And when they see food, especially human food, they will try and get it.”

Although macaques have become more visible — no thanks to social media — their numbers in Singapore have dropped over the years to an estimated 1,500 individuals.

Over the years, reports of conflict have risen and most of the time, efforts to allay peoples’ concerns came in the form of trapping, removing them and culling them. Since 2013, over 1,000 macaques were culled as a result of complaints.

“A lot of people think that trapping and removal is a solution. Just like us, monkeys live in families. They have an alpha male,” explains Anbarasi Boopal (Anbu), Co-CEO of ACRES. “The leader keeps the peace in the troop.”

“If you remove the leader, the rest of the males could split into two troops. Basically, there will be a mutiny. The peace is completely destroyed. And guess what, the estate will have two troops to manage now, and who has absolutely no discipline because the leader is gone,” continues Anbu, referencing the clashes faced by residents who live in estates close to forests.

And with the COVID-19 pandemic ongoing, the inability to travel has prompted more Singaporeans to rediscover their own backyard. As visitors throng the parks, encounters with wild animals have increased.

“During the circuit breaker, the animals did not see a lot of people so they got themselves a bit more comfortable in the areas, and suddenly they are going to see a huge crowd of people coming in, and that opens up the potential for human wildlife conflict situations.” recalls Anbu.

She emphasises the dire need for more sustainable methods, like education, to help move the country towards coexistence with wildlife.

A city in nature

As Singapore moves towards the vision of being a city in nature, boundaries between greenery and urban settings are already beginning to blur.

“Forests are being cleared to create residential pockets,” says Anbu, “and when they create residential pockets like a Housing and Development Board (HDB) estate, they are going to put greenery again.

“Sooner or later we are all going to encounter animals like monkeys.”

Even if one doesn’t like monkeys, it is important to recognise that they are crucial for our forests and green spaces to thrive, shares Anbu.

“They are very important seed dispersers in the forest. Without them, we will not have a very lush green forest in our surroundings.”

“If we do not have a healthy forest, which is like the lungs of our ecosystem, then we won’t have a good reservoir, which means it will affect our water sources. It's going to affect us at the end of the day, so we have to protect these monkeys.”

She shares that many Singaporeans care about the wild animals here but are unsure of what to do when they encounter one.

“They don’t know that you can minimise conflict if you play an active role,” adds Anbu.

ACRES encourages more Singaporeans to take ownership of the space they live in and to empower themselves with knowledge. To spread the word to the community, ACRES also relies heavily on donations and their network of volunteers, who help out whenever they can. “Without volunteers, I don’t think we can try to do a lot of things we are trying to do now.” says Anbu.

She adds, “Being a volunteer at ACRES, it ultimately makes you feel that you’re a catalyst in the movement. You’re not just there helping animals — yes that’s the big plus point, that’s the million dollar moment to many of us — but you are there changing the mindsets of people.”

Anbu dreams of a day where park goers know what to do when they encounter wild animals, and for residents living near forests, to know how to handle their food trash and handle passing macaques.

“That’s a million-dollar moment for us,” says Anbu. “That means they are practicing coexistence.”

About Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (ACRES)

Founded in 2001, ACRES is a non-profit animal protection organisation that is dedicated to spreading awareness, education and also wildlife rescue. It is run by a small but passionate team of full-time staff and is supported by dedicated volunteers and donors.

BEHIND THE SCENES

How do you film macaques when you have a fear of them? Hear from our producer, Pei Lin, as she shares her experience on the ground.

Contributors

Director & Editor

Producer, Camera & Writer

Camera

Animation

Lights & Shadows

Production Assistant & Colourist

Executive Producer

Please rotate your device to continue the slideshow

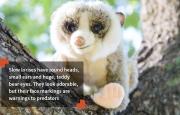

Creature Feature

Click on the animal icons to get to know our wildlife stars better!

Creature Feature

Tap on the animal icons to get to know our wildlife stars better!